Table of Contents

The fundamental facts that brought about cooperation, society, and civilization and transformed the animal man into a human being are the facts that work performed under the division of labor is more productive than isolated work and that man’s reason is capable of recognizing this truth.

– Ludwig von Mises

The previous chapters discussed economizing acts and exchanges which are performed in isolation. Labor, capital accumulation, and technological ideas for production are all tasks which humans can use to improve their well-being, without needing to interact with others, by exchanging labor for leisure, immediate gratification for delayed gratification, and new technologies for old ones. But humans are social animals; born into a family and extended social order, they spend their lives interacting with others. Exchange with others is an instinctive and natural part of life, something children perform at a young age. The most economically notable way in which people can interact is through trade or free exchange. This chapter examines and explains the rationale for and benefits of free exchange. The following chapters build on this one to develop a more complete picture of impersonal exchange in the monetary market order.

Exchanging goods with others brings an important complexity to economic decision-making, which is the idea that the other individual in an economic interaction has his or her own will. When carrying out economizing acts with material goods, such as production, consumption, and capital accumulation, the individual is only dealing with inanimate objects that have no will or consciousness of their own. But when dealing with others, the individual is confronted with another will, one with its own desires, preferences, ends, and actions.

There are only two modes of interaction between people: consensual and coercive. With consent, all involved individuals are partaking in an activity that is agreeable to them all. They willingly choose to partake in the act, without engaging in violence, or the threat of violence, against one another. Trade, or free exchange, is a prime example of a consensual arrangement; both individuals willingly agree to exchange goods because they identify that they can benefit from the exchange. The mere fact of two individuals choosing to exchange goods with one another willingly allows us to necessarily deduce that they both expect to benefit from the arrangement. Had they not favored the outcome of the exchange, they would not have engaged in it in the first place. This is why trade is often referred to as a positive-sum game: The total gain accruing to each participant in trade is necessarily positive. Otherwise, they would not have engaged in it.

Exchange implies the ability of two individuals to use their reason to arrive at an arrangement that benefits them both and hurts neither of them. Only reason allows two people to interact in a way that is beneficial to both because it allows them to foresee the benefits of cooperation and how cooperating will improve their situations.

The only alternative to consent is coercion, which is the imposition, through violence or the threat of violence, of one party’s will on the other. Whenever coercion is involved in a human interaction, it can necessarily be concluded that one of the parties in the interaction is worse off than they would have been had the interaction not taken place. Were this not the case, employing coercion to force him to agree to the interaction would not have been necessary; he would have taken part willingly. Coercion can be thought of as a zero-sum game, but it is more likely a negative-sum game. In the case of theft, the thief can take some of the victim’s property, increasing his own well-being at the victim’s expense. While quantitative economists might refer to this as a zero-sum interaction, this is based on the faulty premise that value is objective and the thief ’s gain is equal to the victim’s loss. But since value can only be understood as a subjective phenomenon, we cannot assume both individuals value the good equally.

A family heirloom the thief values at pennies may have extraordinary subjective value for the owner. But because the thief has not purchased the item from the victim in a negotiated exchange, the value of the item to the victim has not been expressed. The thief has not offered something of sufficient value in exchange, nor even learned what that might be. So it is perhaps more likely that the value gained by the thief is less than the value lost to the victim.

Further, in the case of violence, physical damage could happen to either or both the aggressor and the aggressed, causing them to both suffer. Violence is destructive and the damage from inflicting it can in fact be larger than the loot gained. Moreover, the initiation of violence always brings with it the threat of retaliation. Further, engaging in violence against others results in a marginal increase in the normalization of violence and the likelihood of the perpetrator becoming a victim.

No matter how attractive the spoils of coercion may be, they will always pale in comparison to the rewards possible from cooperation. Man’s animal instinct elicits fear of the other, but man’s reason can also identify the benefits of cooperation, in effect creating a civilized society. This can be illustrated using the example of Robinson Crusoe encountering another man, Friday, on what he thought was a deserted island.

When confronted with Friday, Crusoe faces two options: coercion or consent. Coercion may seem instinctively tempting: Crusoe could try to enforce his will on Friday, subjugate him and enslave him, or murder him and take his property. Each of these entails a gain for Crusoe, but being unbearable to Friday, they would very likely lead to a violent confrontation between the two men, and the outcome would be uncertain for both. Crusoe could be defeated, enslaved, or killed himself, or he could get hurt even while triumphing. If he does triumph, he may be able to acquire all of Friday’s possessions and slave labor, but he would not be able to secure Friday’s enthusiastic cooperation to work productively, since Friday knows his output would be primarily for Crusoe’s benefit. Crusoe would never be able to trust Friday, who could always seek to harm him any time he could. Conflict and violence leading to death are the expected outcome of this path.

On the other hand, if the two men decided to cooperate with each other and only engage each other on terms acceptable to both, they would likely both be much better off in the long run. Whatever material possessions Friday currently owns, which Crusoe could take, pale in comparison to the goods he could produce if he were to remain alive and free to work, be as productive as he could, and participate with Crusoe in a division of labor.

If Crusoe and Friday both willingly respect each other’s sovereignty and property, the two of them are able to produce securely and then exchange the goods they produce. The benefits that are open to them by cooperating are far larger than anything they could secure if they remain hostile and combative. For all of the amazing benefits one can secure through labor, capital accumulation, and technological innovation alone, a far larger world of possibilities is open to humans if they engage in exchange with others. There are several mental tools and constructs developed by economists over the centuries to help us understand the significance of trade and its enormously beneficial potential. The rest of this chapter elucidates these tools to illustrate how the possibilities of cooperation are far better for all involved than conflict.

Subjective Valuation

The foundation for understanding the economic phenomenon of trade is the concept on which all economic reasoning is based: subjective valuation. Only by understanding that value is subjective does the concept of trade become possible. If value were objective, what would people gain from engaging in trade? Why would they want to exchange something for something else when they value both goods equally? Marginal utilities of exchanged goods must increase for both parties. Each party gains higher satisfaction from the thing they acquire than from the thing they give up.

People are able to exchange objects with one another because they place different valuations on the same objects. Value is not something inherent to objects, nor is it a property objects acquire in certain definitive quantities. Value is assigned by the human mind, and valuation is made at the margin. Individuals assign value to objects based on how much they value them at the specific time and place they make their valuation. This depends on a range of factors, prime among them is the existing quantity of these goods they hold.

It is therefore entirely possible for Crusoe to value an apple more than an orange, while Friday values an orange more than an apple. If Crusoe owns an orange while Friday owns an apple, they would both benefit from exchanging their fruit. We can understand this by thinking about their actions, and what we know about the way humans act. If Friday willingly proposes the trade, and Crusoe willingly agrees, we can only conclude that the trade improves their respective well-being: Since Friday values the orange more than his apple and Crusoe values the apple more than his orange, they both gain from the exchange.

Another way to understand why trade happens is by considering the implications of the law of diminishing marginal utility in the context of interpersonal interaction. Since the marginal utility of each unit of a good declines with the increasing quantity of the good, it will naturally follow that individuals will find opportunities for trade by exchanging the goods they have a lot of for the goods they have only a few of. If Crusoe has an apple tree and Friday has an orange tree, they will likely each have large quantities of their own fruit and none of the other’s fruit. They would likely value the marginal fruit from their individual trees far less than the first fruit they are able to get from the other person’s tree. Crusoe’s orange tree gives him more oranges than he can eat, and after having eaten the majority of the tree’s produce, the last few oranges have very little value to him. He may not even want to eat them. But having eaten no apples before he meets Friday, the marginal valuation he places on the first apple he can obtain from Friday will be relatively high. Friday, in turn, places very little value on the last few apples produced by his tree and would value an orange from Crusoe’s tree much more dearly. Trade allows them both to give up something they do not value highly to obtain something they value more in return.

One common misconception in economics involves confusing value and price. The mere fact that humans willingly choose to engage in exchange shows that this notion is untenable. If a person pays $10 for a good, she is not valuing it at $10, she is valuing it at more than $10 because she willingly gives up $10 in exchange for the good. The seller, on the other hand, clearly values the good at less than $10, as he willingly gives it up for that amount.

While differing subjective valuation explains the rationale for trade, it does not fully capture its benefits and implications because it focuses on the decisions made about the final goods. The more powerful potential implication for trade becomes apparent when we consider the effect trade has on the production process. Two important approaches to understanding human action in interpersonal exchange are the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage.

Absolute Advantage

Trade arises from differences in the subjective valuation of final goods, but it is also an expression of differences in the cost of producing different goods. Even in a primitive setting with no market prices to compare goods, individuals are able to discern the differences in the economic value of different goods, and find opportunities to improve their subjective well-being in transactions where each party gives up things for which they have a lower cost of production to acquire things for which they have a higher cost of production.

Imagine a situation in which Crusoe and Friday subdue their hostile first instincts and instead approach each other peacefully. Crusoe finds that Friday has an abundance of rabbit skins in his cave because he is very good at hunting rabbits, whereas Crusoe is skilled at catching fish. Seeing the abundance of rabbit skins, Crusoe realizes that he desires the rabbit meat and asks Friday if he would be interested in exchanging a fish for a rabbit. Having eaten nothing but rabbit meat for months, Friday accepts the offer enthusiastically. He can barely fish, and every time he tries, he wastes a lot of time and fails to catch enough fish to satisfy his hunger. But now Crusoe is offering him a fish in exchange for a rabbit, which is very easy for Friday to secure. Friday might even be thinking he is taking advantage of Crusoe, who is giving away a precious fish for a rabbit that’s easy to secure, but Crusoe is likely thinking the same thing. He is finally able to secure an elusive rabbit, and all he needs to do to get one is to provide one of the many fish he is easily able to catch. In this situation, both men give up something they can produce at a low cost to acquire something they value much more. In a sense, they are both taking advantage of each other.

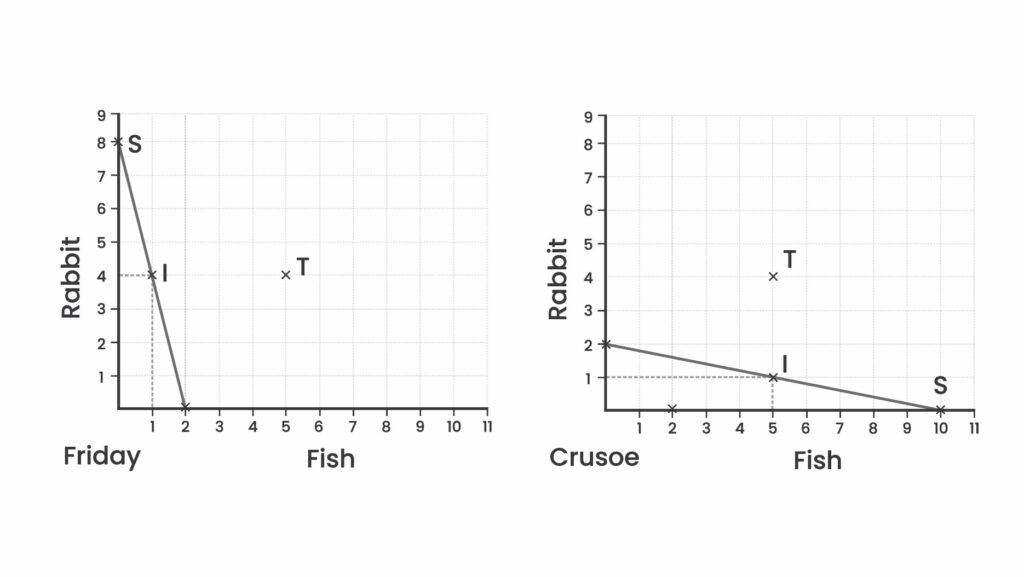

This situation can be illustrated with a hypothetical numerical example. We can present the production possibilities graphically using a production possibilities frontier—a line that illustrates all the possible combinations of both goods that can be produced. Imagine that in a day’s work, Friday can catch 8 rabbits or 2 fish, while Crusoe can catch 2 rabbits or 10 fish. If they work independently and do not cooperate, these amounts would represent the respective limits on how much they could each consume daily. Friday could consume either the 8 rabbits or the 2 fish he can catch, and Crusoe could consume either the 2 rabbits or 10 fish he is able to catch. If, in isolation, they both decided to split their workday equally between fishing and hunting, Friday would end the day with 4 rabbits and 1 fish, while Crusoe would have 1 rabbit and 5 fish, as shown in points I in Figure 17. The sum for both would be 5 rabbits and 6 fish.

If Crusoe were to attack Friday and try to rob him, he might be able to take all the food Friday had, but that would cause Friday to starve to death, leaving Crusoe with nothing but his own production, as in his original state. But if they decided to cooperate, they could both benefit from the differences in their catches. Because Crusoe notices that Friday has an abundance of rabbits but not many fish, he suggests trading some of his rabbits for Crusoe’s fish. Rabbits are abundant for Friday but fish are not, so exchanging a fish for a rabbit is a winning trade for Friday, and the opposite is true for Crusoe.

The exchange illustrates to Friday that the best way for him to obtain fish is to actually hunt rabbits and exchange them for fish, while Crusoe realizes that he can obtain more rabbits by fishing and exchanging the fish for rabbits than he would by hunting rabbits. The end result is that it makes sense for them to each specialize in the good they can produce more cheaply. If they specialize, and Crusoe produces only fish and Friday only rabbits, as shown in point S in Figure 17, their combined daily production would be 8 rabbits and 10 fish, which is 3 rabbits and 4 fish more than they would have had if they had remained hostile. If they split their harvest in half, they each end up with 4 rabbits and 5 fish, as shown in the point T.

By simply specializing in the production of the cheaper good, they have both produced more fish and rabbits than if they had each split their time and effort between producing both. This result almost seems like a magic trick: both work the same number of hours, and yet they both end up with more rabbits and fish to eat, and are both better off. This is not a one-off benefit like the loot from aggression, but a sustainable improvement in both their lives that can continue for as long as they continue to trade amicably with one another. In effect, every morning, they both wake up facing a choice: Cooperate and eat more or be hostile and eat less. By allowing each person to dedicate their time to the production of the good that is less expensive for them, trade increases the productivity of both parties. Had one of them killed the other, the “winner” would never gain as much as he would gain from cooperating voluntarily with the other.

Comparative Advantage

The rationale behind absolute advantage is intuitive and easy to understand. Each person specializes in what they can produce at a lower cost, leading to more production of all goods. But the concept of comparative advantage is a more general and powerful explanation of the benefits from trade as a consequence of differences in the opportunity cost of goods, irrespective of the nature and magnitude of the differences in productivity between participants. Trade can be mutually beneficial even if one individual is more productive in the production of both goods than the other person, because of the differences in the opportunity cost of goods for both individuals. The fact that human time is the ultimate scarce resource means that cooperation between two people is beneficial to both of them, even if one is more productive at generating both goods, because their cooperation allows them to dedicate their scarce time where it is most productive.

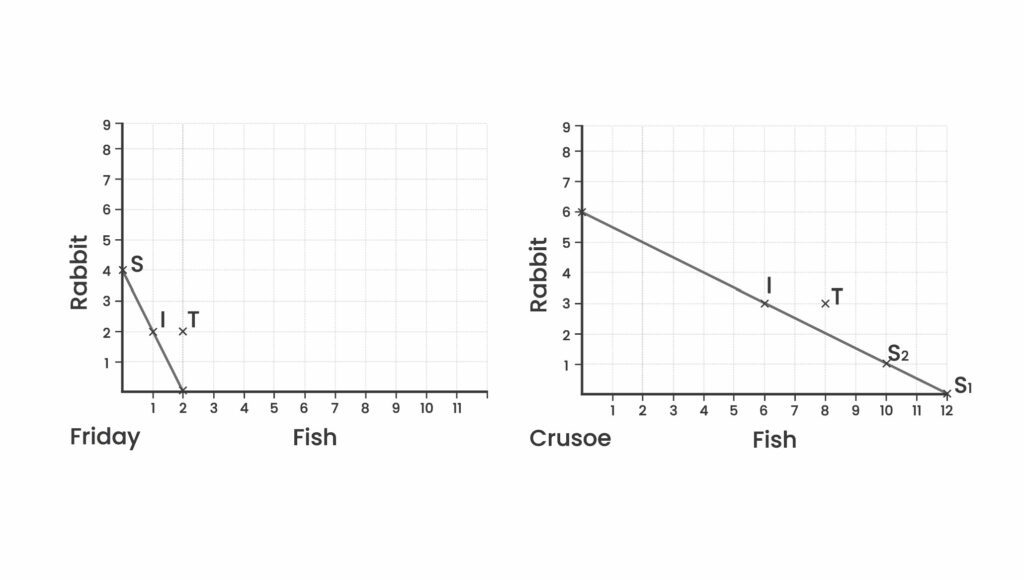

Imagine if, in the example above, Crusoe were more productive at both fishing and hunting, and he could produce 6 rabbits or 12 fish per day, while Friday could only produce 4 rabbits or 2 fish. This does not mean the 2 cannot benefit from the division of labor. Had the 2 men produced and consumed in isolation, and each spent half their day hunting and the other half fishing, Crusoe would have 3 rabbits and 6 fish, while Friday would have 2 rabbits and 1 fish, for a total of 5 rabbits and 7 fish. If they cooperate and specialize, Friday catches 4 rabbits and Crusoe catches 12 fish, as shown in point S. If they prefer to have more rabbits, Crusoe could spend a part of his day fishing, and they would end up with 5 rabbits and 10 fish, as shown in point S2. In this case, they would have added 3 fish to their daily consumption by specializing. There are various other combinations of fish and rabbits that they could produce, depending on their taste and preference for both. As long as the specialization allows each producer to focus on the good with the lower opportunity cost, they would have more subjectively valuable production than they would in isolation.

Both Crusoe and Friday would work the exact same number of hours, and yet they would be able to produce more output than they had before, even though Crusoe is more productive at both hunting and fishing. The fact that the two men have a different opportunity cost for the two goods means that they can improve the quantity they produce by each spending more time producing the good for which they have the lower opportunity cost. Because each person spends their time producing the good with the lower opportunity cost, they produce more of the final products they both want.

The specialization in this example happens because the opportunity cost of a rabbit for Crusoe is 2 fish, whereas for Friday, it is half a fish. This opportunity cost is expressed graphically as the slope of the production possibilities frontier curve. In isolation, for every time period in which Crusoe needs to secure 1 rabbit, he needs to give up the time necessary to secure 2 fish. But Friday has a different opportunity cost. He can produce twice as many rabbits as fish in any particular time period, so he needs to give up only half a fish to obtain an extra rabbit. If someone were to offer Friday a whole fish in exchange for 1 rabbit, he would be very happy to take it. Similarly, if Friday offered a rabbit to Crusoe in exchange for a fish, Crusoe would be happy to accept the offer, as this is a cheaper way for Crusoe to obtain the rabbit than producing it himself.

Crusoe has two options for securing an extra rabbit: 1) Reduce the time spent fishing and give up 2 fish in order to have enough time to hunt 1 rabbit, or 2) give Friday anything more than half a fish to get him to part with one of his rabbits. The first method costs Crusoe 2 fish, whereas the second costs him a sum larger than half a fish. In support of his own self-interest, Crusoe chooses to cooperate with Friday, and the same reasoning compels Friday to cooperate with Crusoe. The mere existence of differences in opportunity cost between the two means that they can coordinate to allocate their own labor in a way that maximizes the total output they can share based on terms that they agree on initially. The difference in opportunity cost is the advertisement for the trading opportunity. It signifies to each person that the other can provide what they want at a lower cost and that optimizing one’s production to accommodate the possibility of trading with someone increases the productivity of both parties.

No matter the difference in productivity between the two, the difference in opportunity cost means that trading will change the allocation of labor between them to create increased output. These opportunities for trade emerge in the real world without economists having to study them and elaborate them to trading individuals. As humans interact, they notice the differing valuation of different goods between people. These differences present opportunities for exchange that benefit both parties. The logic applies at the level of individuals in a family, village, city, country, or across countries. Differences in the opportunity cost of production present opportunities for specialization and people are constantly seeking to take advantage of them.

The differences in preferences and productivity are the drivers for the universally pervasive phenomenon of trade. The mathematical examples are helpful in this regard, but they have been overemphasized in modern economic education, to the point where courses on international trade contain little economic understanding and instead focus on, and test for, mathematical operations tangentially related to these points. The profound insights into the benefits of trade are usually covered only briefly in the early chapters of most textbooks, while the needlessly complex mathematical models take center stage. The mathematical sophistry makes for easier standardized testing, and also transforms these textbooks into a series of elaborate half-baked rationales for government intervention in trade. While the average trade textbook begins by singing the praises of free trade, it quickly degenerates into recycling ancient mercantilist nonsense by slipping it in through irrelevant mathematical models.

Specialization and the Division of Labor

The existence and possibilities of exchange open up for producers the avenue of producing for a “market” rather than for themselves. Instead of attempting to maximize his product in isolation by producing goods solely for his own use, each person can now produce goods in anticipation of their exchange value, and exchange these goods for others that are more valuable to him. It is evident that since this opens a new avenue for the utility of goods, it becomes possible for each person to increase his productivity.

– Murray Rothbard

The motivations for trade can be derived from differences in taste and valuation, as mentioned above, but in an extended market order, they are driven ultimately by differences in the cost of production and intensified by specialization.

Whereas in isolation, man produces what he needs, in a social system, man produces based on what he expects others to need. He need not meet the full diversity of all his needs through his own labor and can instead direct his labor to the areas of production in which he can excel most at serving others. By specializing in producing a good for a market, rather than producing for your own consumption, it becomes possible to dedicate labor toward the place where it is most productive, not where it is merely necessary. In a market economy, your needs are best met indirectly, by using your abilities to specialize in what you do best and exchanging it for the goods and services produced by others. Specialization is therefore another way of increasing productivity. Beyond just an increase in productivity, trade leads to social cooperation and civilized behavior, as the benefits of being able to engage with society peacefully in a division of labor are very high.

In Human Action, Mises explains that specialization is driven by differences in abilities and nature-given factors. In Man, Economy, and State, Rothbard argues that specialization is driven by (a) differences in suitability and yield of the nature-given factors; (b) differences in given capital and durable consumer goods; and (c) differences in skill and in the desirability of different types of labor.

Rothbard’s explanation here is more comprehensive than Mises’, and one can go even further than Rothbard and argue that it really is predominantly the accumulation of capital that drives specialization, particularly in the modern economy.

In the above examples, we took it as a given that there were large differences in the productivity of hunting and fishing between Crusoe and Friday. But in the real world, these differences will most likely be driven by differences in capital stock. Crusoe will have a higher productivity when catching fish because he invested in constructing a fishing rod and a fishing boat, while Friday will be better at catching rabbits because he invested in building traps and spears. The differences in productivity are unlikely to be very large without differences in capital stocks. As technological progress and capital accumulation have advanced over time, they have become increasingly detached from the natural conditions, and as such, productivity and comparative advantage in these industries are primarily driven by the extent of physical and human capital accumulation.

It is reasonable to expect geographic and natural factors to go a long way in determining comparative advantage in agricultural and natural products. Finland will likely never specialize in producing tropical fruits like mangoes, and the Sahara Desert is unlikely to export bottled water. But in a modern industrialized economy, such natural and agricultural products have become a progressively less significant part of economic activity, and of an individual’s expenditure, compared to services and industrial goods. In the modern economy, the driver of specialization is largely the investment of capital in an industry. Places that have invested in car manufacturing over decades have developed the physical and human capital suited to car production, and will likely continue to have an advantage in car production. Places that invest in the infrastructure for the textile industry will likewise develop that advantage. The more sophisticated the economy, and the longer the production structures, the more comparative advantage is the result of differences in capital accumulation, and less the result of differences in natural factors.

The industry with the highest productivity in the modern world is probably the computer and telecommunications industry, which continues to achieve enormous increases in productivity as it enters and invades all industries, making them much more efficient. Competitiveness in this industry is almost entirely separate from natural and geographic factors. The software engineers and programmers in this industry only need the capital infrastructure to be able to produce, regardless of whether they are doing so on a tropical island like Singapore or a frozen Arctic landscape like the north of Sweden. This is another reason I believe modern economics does not focus enough on the importance of capital accumulation and ascribes too much importance to trade and division of labor in isolation. Without extensive accumulation of capital, there would be little scope for the increase in productivity that drives the differences in opportunity cost, which necessitate specialization.

Trade is a phenomenon that emerges naturally whenever humans interact and realize their valuation of different goods differs. As they start to realize they can meet more of their needs by producing for the market than by producing for their needs directly, people become more attuned to the needs of the market and start directing their productive capacities to meet the needs of society. This leads to a society-wide division of labor, wherein jobs are divided among the population. The more individuals can specialize in the production of a good, the more they will improve their productivity over time.

Extent of the Market

Every step forward on the way to a more developed mode of the division of labor serves the interests of all participants … The factor that brought about primitive society and daily works toward its progressive intensification is human action that is animated by the insight into the higher productivity of labor achieved under the division of labor.

– Ludwig von Mises

In the previous sections, we looked at the example of two men on an isolated island benefiting from trading with one another and specializing in the production of the goods for which they have the lowest opportunity cost. This simple example illustrates the rationale for trade and the drivers of gains from trade, but the same logic applies as the number of trading partners increases over time, and the gains only increase as the number of partners increases, as this allows for deeper specialization, more capital accumulation, and increased productivity.

In the one-man economy, Crusoe has to meet all his needs himself. Between hunting, building a home, building weapons to fight off predators, and making his own clothes, he barely has any time to accomplish all of the necessary tasks. He has very little scope for specialization and very little time to develop capital goods in one particular avenue of production because he has to divide his time between many tasks. With another man on the island, both can specialize in half the tasks and trade their products. Only one of them needs to fish, while the other focuses on hunting. The hunter can now dedicate twice as much time to developing spears and traps, while the fisherman can dedicate twice as much time to building fishing rods and boats. As they now each have half as many tasks to complete, they are both able to dedicate more time to each mission, thus becoming better at it, as well as accumulating more capital for it. The extent of capital accumulation and specialization only increases as more people take part in the market and trade with one another.

If Crusoe and Friday were to come across another 20 people living on the island, the scope for specialization would increase even further. Now, only one person would specialize in home building, while another focused on farming, another on clothing, another on hunting, another on building the fishing rods, and another on building spears for hunting. The same logic of increased production that we saw applied to Crusoe and Friday can now be applied to this larger group, with continuously increasing productivity.

Increasing the extent of the market not only increases the productivity of workers, it also increases the number and variety of goods available to members of society. As the number of people in the market increases, and the productivity of individual producers increases, each producer is able to produce from each good enough to cover the needs of an increasing number of people. This effectively frees up workers to pursue production of newer, innovative goods which go beyond the most basic needs.

As the circle within which a person’s trades grows, the productivity and quantity of available goods increase. This observation of the size of the market is a very powerful tool with which to explain economic phenomena. It helps to explain the economic incentive for immigration from rural areas to big cities. A worker in an isolated rural area produces for a small circle of potential buyers, and buys from a small circle of producers. He has to meet a lot of his own needs because there are not professional providers of these services. He has to spend part of his workday producing things for which there are no specialists in his area, in which he is not specialized, and in which his productivity is relatively low. If he were a shoemaker, for instance, he would be responsible for all stages of the production of the shoe, including the design and manufacture, as well as the sole, laces, and cushioning. But if he moves to a large city, he can specialize in whichever of these stages he finds himself most skillful, where his productivity is highest, and he can rely on others for the other stages. He could focus on the assembly of the shoe, while utilizing the designs of specialized and highly productive designers, buying the laces and soles from specialists who make them at a much lower cost than he could make them himself. The shoemaker can earn more, and be more productive living in a large city than he can in a small isolated rural town.

In a world divided into isolated economies of 1,000 people each, there can be no cars, computers, or smartphones. The 1,000 people would be preoccupied with producing their basic survival needs. If these isolated communities start to trade with one another, the extent of specialization increases and capital accumulation in each production process can increase, freeing up more people from basic survival labor so they can pursue the production of capital goods that do not yield immediate consumption goods. As the extent of the market grows, the rewards from specialization increase, because its products can be sold to larger groups of people. The current world market is the largest single market to have ever existed, and it allows for the highest level of productivity ever attained.

The technologically advanced products we use today would simply not be possible in a world with 1% of the current population, or a world of small markets isolated from one another. For a modern car factory to be able to produce the number of cars it does, at the price it can produce them, requires a large number of people specialize in increasingly specific and arcane tasks, which are only possible when the output is large and can be sold to larger markets. A modern carmaker has engineers who spend many years training and focusing on very minor aspects of the production of the car, such as the windshield. Without the ability for the carmaker to sell cars to large markets, the degree of specialization would necessarily decline, and along with it, the sophistication and value of the product, and the productivity of the workers.

It is truly a marvel to think of the degree of specialization of tasks required to make modern products. In a famous essay, Leonard Read attempts to outline the degree of cooperation needed to produce a modern pencil. Even though a factory assembled and produced the pencil, there is no single human who knows how to produce the pencil from scratch. The factory that assembled it was merely one stage of a long production process involving countless specialized individuals worldwide. From the cutting of the wood, to the processing of the rubber that goes into the eraser, to the metals that go into the holder of the eraser, countless individuals had to cooperate to secure each of these materials in their raw form, transport them to the plants where they were processed, and turn them into the product that the pencil factory can assemble. This division of labor only becomes possible because of the large market in which these producers trade. Should all these people decide to not trade with the world, all their days would be spent on basic survival. By cooperating and trading, they are able to specialize in the production of highly sophisticated goods, with a high productivity, and to consume the products of the specialization of others at a very low cost. The extremely complex production of pencils is arranged, across the world, without a single central planner aware of all its details. The output is tens of billions of pencils produced each year, and available for increasingly cheap prices.

As the market with which an individual is able to trade increases in size, the individual is able to select from a growing number of producers and sell to a growing number of consumers. He can specialize in increasingly specific tasks, which allows for an increase in the division of labor and the development of more sophisticated products. He is able to accumulate increasing quantities of capital to perform his task and thus achieve increasing productivity performing it. The best market with which an individual can trade is the largest market possible: the entire world. Individuals who live in countries with no or low trade tariffs are able to increase their productivity by specializing in very specific tasks they can sell to the highest bidder in the world, and they are able to increase their living standards by choosing the best and most affordable products for themselves from producers worldwide.

This insight also helps us understand why productivity, income, and quality of life rise as a society becomes better integrated into global trade. The tiny island of Saint Helena is located in the South Atlantic Ocean, 1,950 kilometers west of Cape Town and 4,000 kilometers east of Rio de Janeiro, and has a population of around 6,000 people. Trading with the rest of the world is very expensive for Saint Helenians, as it involves very high transportation costs. All capital imported to Saint Helena will be very expensive, making domestic production more expensive than better-integrated locations. Imported consumer goods for Saint Helenians are expensive because of the cost of trade, and their exports will be expensive to the rest of the world.

We can observe a similar pattern when government officials implement policies that effectively make their countries similar to Saint Helena in its isolation, namely trade restrictions. By imposing tariffs on trade, governments increase the cost of trading with the rest of the world, effectively reducing the extent of the market for individuals in their country. The world’s goods become more expensive, and the possibilities for specializing are reduced. Among the most isolated economies on Earth are North Korea, Cuba, Eritrea, and Venezuela. Unsurprisingly, productivity and living standards in these economies are very low. In the past, when Venezuela was a free-market economy open to the world, it had one of the world’s highest standards of living.

At the other extreme from Saint Helena and the isolationist economies stand the world’s freest trading economies, whose citizens are able to trade with a very large global market regardless of the size of their own economies. The citizens of Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, and Switzerland face the fewest impediments to trade with the rest of the world, and as a result, the productivity and living standards of their residents are among the highest in the world. When a citizen of an isolated economy wants to buy a good, she is only able to obtain it from domestic producers. When the citizen of an open economy wants to buy the same good, he is able to choose products from the entire planet. Citizens of the open economy can be far more productive because they can engage in production processes that sell to the entire planet, generating more revenue, and allowing for more investment in lengthening the production process and increasing its sophistication.

The absence of trade restrictions between the early American states significantly boosted the economic rise of the U.S. Free trade in North America allowed a very large population to trade among itself with increasing specialization, on top of having relatively low tariffs on international trade. By the end of the nineteenth century, the U.S. was the largest country in terms of population of all the western economies that industrialized in the nineteenth century, giving it a significant economic advantage and facilitating greater specialization and increased productivity. Had there been trade barriers erected between different states, it is highly unlikely the U.S. would have advanced as much economically.

Economics, as a field of study, attempts to explain the universal pervasiveness of trade. It is no wonder that humans are constantly attempting to engage in trade with one another, and trade encourages humans to moderate their aggressive and hostile instincts toward others and seek productive cooperation instead. The ability of strangers who are not connected by bonds of family or kinship to arrive at a mutually beneficial exchange is one of the basic building blocks of human civilization. The extent to which strangers can expect to deal peacefully with one another, respecting each other’s bodies, property, and will, is the extent to which they live in a civilized human society.