Table of Contents

Every kind of human arrangement is connected in some way or other with money payments. And, therefore if you destroy the monetary system of a country or of the whole world, you are destroying much more than simply one aspect. When you destroy the monetary system, you are destroying in some regards the basis of all interhuman relations. If one talks of money, one talks about a field in which governments were doing the very worst thing which could be done, destroying the market, destroying human cooperation, destroying all peaceful relations between men.

– Ludwig von Mises

Banking

As time preference declines, individuals save more, and consequently, invest more, which tends to lead to an increase in productivity and, in turn, increases the amount of savings available for them. As savings increase and the division of labor becomes more complex, the management of money itself becomes a service provided on the market by specialized professionals. The development of the division of labor leads to increases in specialization across all goods and services, and money is no different. As with food, clothes, or houses, specialization increases the productivity with which a good is provided on the market. Banking is the industry that specializes in the management of money, and it has two essential functions: managing deposits and investments.

On an individual level, we can see how lower time preference leads to delayed gratification and increased savings, investment, productivity, and economic abundance. At the level of the market economy, with the division of labor occurring on a large impersonal scale, and the use of money as a common medium of exchange and saving, the banking industry increases the productivity of saving and investment, allowing for greater capital accumulation and higher productivity. Members of society benefit from others lowering their time preference in this way. That is to say, other people’s savings increase the productivity of your labor.

The first job of banking is to help savers maintain the wealth they have accrued and protect it from theft and ruin. As individuals’ homes are optimized for location, comfort, and various other characteristics, they are not optimized for resisting theft. An increasingly specialized economy will provide individuals and firms with the opportunity to store their wealth in facilities specializing in secure storage. Banks would accept deposits and charge their owners for the privilege of using the facilities. Building a facility specializing in securing savings allows its building to be optimized for security and safety from theft or ruin. By charging a small fee to many wealth holders, bank owners finance the construction and operation of safe facilities that are less likely to be robbed than individual homes or workplaces. In its basic form, when done safely, sanely, and honestly, deposit banking is a boring and largely uninteresting market good that does not merit much economic analysis. It is only when deposit banking is abused that the interesting and tragic consequences unfold. Unfortunately for savers, deposit banking is so commonly abused that safe and boring banking has become a thing of the past.

Credit

The first function of banking is to hold savings on behalf of their owners. The second function is to invest these savings in pursuit of profits that increase them while taking the risk of losing them. Extending credit allows the saver to make a return on their savings by deploying it in the service of an entrepreneur who has a business engaged in economic production. By abstaining from consuming and by abstaining from saving money, the saver becomes an investor, and she makes her savings available to purchase inputs for a production process. The factors of production are then combined to produce the outputs, which are sold on the market, ideally at a revenue that exceeds costs, rewarding the entrepreneur and the capitalists with profit. Should the business fail to make a profit, the creditors stand to lose their savings.

Whereas a capitalist lends her own money to an entrepreneur, a bank lends the money of savers, effectively specializing in the allocation of investments while leaving the savers to specialize in whatever it is that earns them their income. The introduction of specialization and division of labor into the job of capital investment allows its productivity to increase. It allows individuals to invest amounts of money they would otherwise have no obvious use for investing in their own line of work. Their ability to invest becomes no longer contingent on the ability of their own business to grow. By investing in lines of production unrelated to their own industry, investors are able to hedge against the failure of their business or disruptions to their industry.

The task of bankers is to act as the intermediary between the saver and the entrepreneur. They perform due diligence on a large number of potential investments and make an entrepreneurial judgment on which projects are worthy of financing with savers’ savings. The job of the investment banker allows the savers to delegate the selection of investments to professionals and allows entrepreneurs to seek the savings they require from the bank rather than attempt to gather them from unspecialized individuals.

Not all bank credit is the same. Mises makes an important distinction between two different types of banking credit: Commodity credit and circulation credit. The rest of this chapter discusses commodity credit, while the next chapter will focus on circulation credit.

Commodity Credit

Mises uses the term commodity credit to refer to the credit which is borrowed by banks and granted to entrepreneurs, making banks mere intermediaries profiting from the difference between the interest rate they pay their lenders and the rate they charge their borrowers. This difference arises from the expectation that the bank’s specialization will allow them superior returns over the lender attempting to find counterparties all by themselves. For a bank to be an intermediary granting commodity credit, its lending must follow the golden rule, which is according to Mises: “The credit that the bank grants must correspond quantitatively and qualitatively to the credit that it takes up. More exactly expressed, ‘the date on which the bank’s obligations fall due must not precede the date on which its corresponding claims can be realized.’ ” In other words, it is essential that the quantity of the credit that the bank extends does not exceed the quantity of savings that savers have lent to the bank.

Should there be a discrepancy between the quantity of credit the bank borrows and the quantity it lends, or should there be a discrepancy between the maturity dates, then the bank is no longer engaged in lending of commodity credit, but in circulation credit. In this case, the bank is not merely transferring the money of savers to entrepreneurs; it is issuing credit that is being used as money, effectively inflating the money supply, with substantial consequences discussed in the next chapter.

The distinguishing feature of commodity credit is that it involves a sacrifice on the part of the lender. Someone has to forgo access to monetary instruments equal to the full value of the loan for its entire duration in order for the loan to be issued. The lender forgoes the money in the present in the expectation of receiving a larger payout in the future. The borrower, on the other hand, gains access to the money in the present but pays an added cost when repaying the loan. The interest rate at which the loan takes place illustrates the differing valuations placed on time by each party. The lender has a lower time preference, which makes the value of the principal and interest in the future higher than the principal today for her, making lending at that rate profitable. In turn, the borrower has a higher time preference, and so the principal and interest repayment in the future are worth less to him than the principal today. The difference in time preference between the two is what creates the opportunity for them to agree on an exchange.

Interest Rates

In mainstream economics, interest rates are viewed as the determinants of savings rates, as individuals compare their time preference to interest rates and decide if they will save. But that is only tenable in a centrally planned world where interest rates are set by the government. In a free market, what would determine the interest rate? It would be determined by people’s time preferences. It cannot be determined by the productivity of projects funded since there are projects at all levels of productivity. What determines which projects are funded and which are not is not their productivity, but the availability of capital, which is a function of time preference. Time preference makes the capital available, and entrepreneurial judgment attempts to allocate it to the projects with the highest expected returns.

The capitalists’ function is thus a time function, and their income is precisely an income representing the agio of present as compared to future goods. This interest income, then, is not derived from the concrete, heterogeneous capital goods, but from the generalized investment of time. It comes from a willingness to sacrifice present goods for the purchase of future goods (the factor services). As a result of the purchases, the owners of factors obtain their money in the present for a product that matures only in the future.

The ratio of the value assigned to a present good and the value assigned to an identical future good is called the originary interest. Originary interest measures the percentage discounting on the valuation of a good an individual requires to receive the good in the future. For instance, a person who expects to receive a shipment of 10 bushels of corn today would have to be offered a certain premium to delay acceptance by a year. The percentage increase in the quantity that needs to be offered to that individual to delay their consumption is the originary interest rate.

From the perspective of Austrian economics, all economic phenomena have their root in human action, and interest is no different. Time preference is what creates the phenomenon of originary interest. The ingrained time preference of individuals is inevitably reflected in a premium for present goods over future goods; this is in turn reflected in the market for money, which is a market good no different from all others. Assuming the value of the currency remains constant, a person who is owed a payment of $100 today would need to be offered a premium on it in order to delay accepting the payment by a year, in the same way, they would need to be offered a premium on the bushels of corn. The existence of time preference is itself the determinant and originant of monetary interest.

The presence of money allows originary interest to be harmonized across goods and individuals. This happens through the emergence of a credit market, in which future obligations of money are traded for present payments, establishing a general discount rate of the future, or an interest rate. Deviations of discount rates for particular goods from the prevalent market interest rate for money will create opportunities for profitable arbitrage in these goods, bringing the interest rate on all goods into a narrow range, reflected on the market as the market interest rate. Hoppe describes this market-determined interest rate as “the aggregate sum of all individual time-preference rates reflecting the social rate of time preference and equilibrating social savings (i.e., the supply of present goods offered for exchange against future goods) and social investment (i.e., the demand for present goods thought capable of yielding future returns).”

While individual capital goods have their own markets in which they are traded, in a modern monetary economy, capital is traded as an abstract good through the borrowing and investment of sums of money. Societal monetary savings are made available to financial institutions who lend them to entrepreneurs who use them to purchase capital goods. The demand for investing and purchasing capital goods is practically infinite, as coming up with entrepreneurial ideas is far easier and less costly than deferring the consumption of present resources. The limiting factor on the quantity of investment is the quantity of cash saved, and that in turn is restricted by the desire and need to consume—by time preference being positive. The existence of capital goods, and capital markets in general, is entirely contingent on individuals lowering their time preference enough to provide the capital needed. The demand is for investable funds, and the borrowers’ expected rates of return do not determine interest rates, as there are projects expected to offer a very wide range of returns. Time preference determines the quantity of loanable funds, which will then go to fund the projects with the highest expected returns, whose borrowers are willing to pay the highest interest rates. The more funds are saved, the lower the interest rate, the more projects can be funded, and the lower the expected rate of return on the marginal project. More saving also results in a growing diversity of funding mechanisms, increasing the liquidity of the market for capital and its options.

By deferring consumption to provide capital for investors, the capitalist incurs the cost of the operation in terms of time. The capitalist invests the time in the enterprise by sacrificing present goods for future goods. This sacrifice is what allows the workers and the providers of the input goods for the process of production to get paid before production is concluded and the goods are sold on the market. In the same way that a fisherman living in isolation needs to sacrifice time spent catching fish in order to build a fishing rod, someone must defer consumption of resources for any production process to take place. The entrepreneur uses the resources and sacrifice of the capitalist to pay the workers, landowners, and capital good sellers in the present. The process of production takes place over time, and the entrepreneur sells the final goods. Only then is the capitalist paid the agreed-upon interest rate. The workers and the sellers of input goods get paid as they perform the service, not as the product is sold, because they are not contributing their time to the endeavor, and they are not deferring consumption. The capitalist is the one who defers consumption, and in doing so, contributes the time for the resource goods to mature into final products. Time is an essential input into the process of production, no different from labor, land, and capital, and the capitalist receives compensation for it from the entrepreneur in the form of the prevalent market interest rate.

Should the revenue from selling the final output of the production process exceed the costs paid to the providers of the labor, land, capital, and time, the business is profitable. It is important here to distinguish between the interest and the profit. The profit is derived from the difference between the market valuation of the input goods and the market valuation of the final goods. The interest is merely the payment for the time input provided to the production process by the capitalist. The profit or loss is the difference in market valuation of the inputs and outputs.

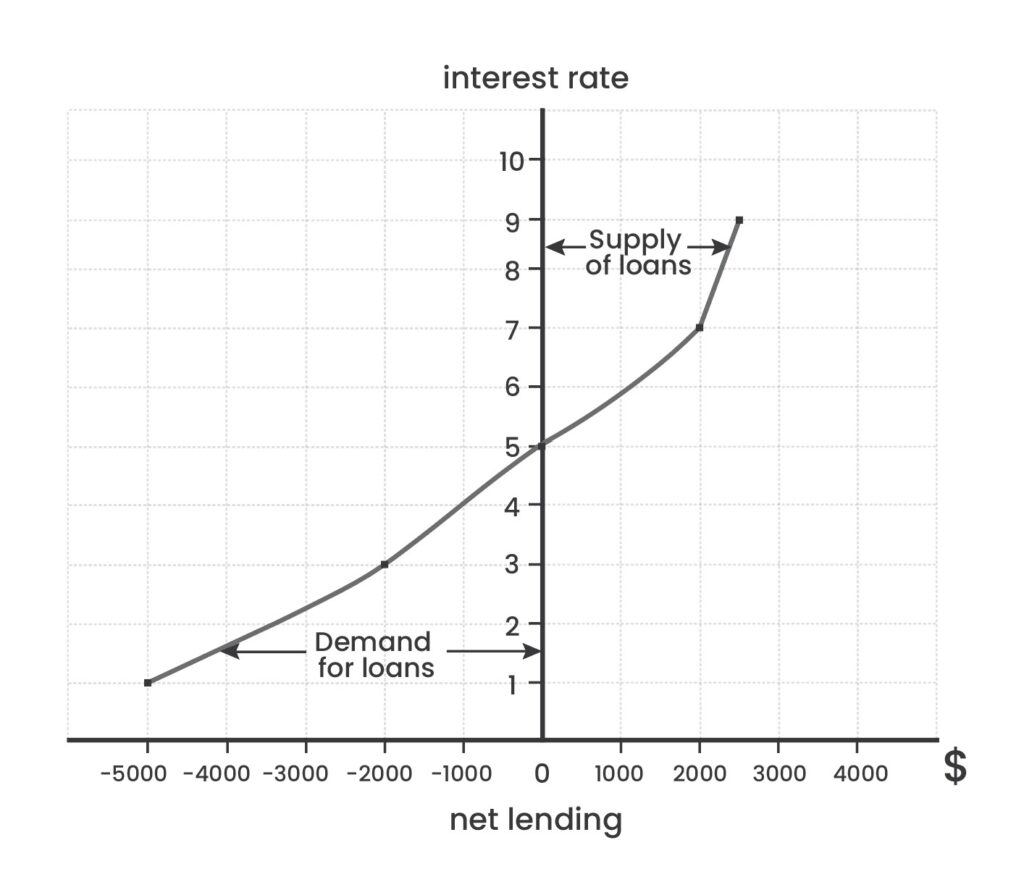

In the market for capital, individuals have value scales ranking present goods against future goods. Present goods are more valuable than identical future goods; humans effectively place a discount on future goods. Individuals compare their own discount rate for goods to the market interest rate. If a person’s personal discount rate is higher than the market interest rate, she would demand to borrow from the market, since she would value the repayment of the principal and interest in the future less than the principal in the present. If, on the other hand, her personal discount rate is lower than that of the market, she would lend her cash savings on the capital market, as she would value the repayment of the principal and interest higher than holding the present cash savings. The larger the disparity between personal time preference and market interest rate, the larger the quantity of borrowing and lending demanded.

We can illustrate this relationship graphically: An individual has a “time market” curve, which determines the quantity of money she would like to borrow or lend at any given interest rate. For a saver who places a 5% annual discount on the future, a 5% market interest rate leaves her not wanting to borrow or lend, as the market has the same discount level as she does. If the market interest rate were to rise 7%, she is now offered a tempting opportunity: If she forgoes enjoying a certain sum of money today, she could lend it and receive it along with a 7% interest rate in a year’s time. Since she discounts next year’s money at a rate of 5%, this loan would give her a return of 2%. If, on the other hand, the interest rate were to drop to 3%, then she would have the incentive to borrow from the capital market. Borrowing at 3% means she has to repay in a year 103% of the principal, and since he discounts the future at 5%, her repayment is lower than the value of the loan to her today. Naturally, as the interest rate rises, the demand for borrowing declines while the demand for lending increases.

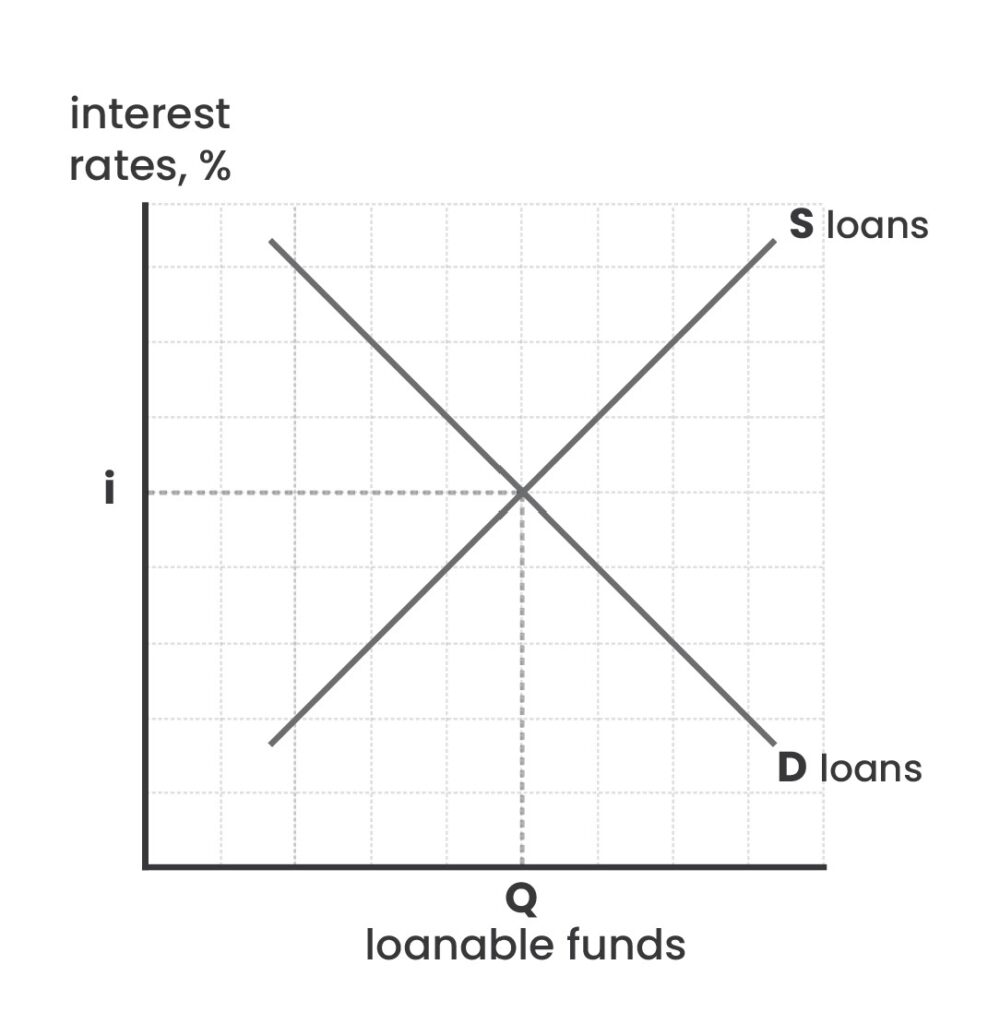

At the capital market level, all of the individual time preference and money demand and supply curves are effectively aggregated into economy-wide supply and demand curves for loanable funds. At any given interest rate, there is a total amount of capital that is available for lending and demanded for borrowing. Since the capital available for lending increases as interest rates rise, while the capital demanded for borrowing decreases as interest rates rise, the two quantities must only meet once, at the interest rate which clears the market capital, where the quantity of loans is equal to the quantity of capital saved from consumption and made available to borrowers.

It is important here to reemphasize that time preference and future discounting are subjective phenomena and they are not measured by interest rates. What exists in acting humans’ minds is an ordinal ranking of future and present goods, and it is by being exposed to an offer of an interest rate that they are able to ordinally compare the implied discounting available on the market to their personal discounting, and decide between the two. Further, there is no such thing as a prevalent market interest rate, only individual interest rates, which are affected by the individual projects and the individuals involved. It is useful to think of the market interest rate, as with the market equilibrium price, as a tool to help understand these economic concepts. While the tools of mathematical analysis are useful to communicate an understanding of market phenomenon, it is important to not fall into the trap of treating them as scientific units based on accurate measurement of constants.

As capital is allocated to economic production, productivity increases and incomes rise. With secure property rights and increased certainty of the future, time preference would be expected to continue to decline further, making individuals more likely to defer consumption, more likely to save, more likely to lend, and less likely to borrow. The abundance of loanable funds allows for the financing of an increasing number of productive enterprises at progressively lower interest rates. Unless interrupted by war, pestilence, depredation, the perverse regulatory burdens of centralized governments, or violently imposed easy fiat money, this virtuous cycle of improving material well-being continues, which can be understood as the process of civilization. But how far can this process go? How low can interest rates go?

Can Interest Be Eliminated?

The topic of interest lending is a historically, politically, and religiously charged one. Interest lending has been forbidden by many religions and is still viewed as immoral by many people worldwide to this day, even in a monetary system that relies heavily on credit creation. Mises and the Austrian economists have gone to great lengths to explain it as an inextricable part of a market economy and to make a case for why it is a productive institution in the market economy. From the Austrian perspective, interest is not an alien invention imposed on society by leaders. Like all economic phenomena, interest has its root in human action and in the time preference that is positive in each individual. As Mises explains:

We cannot even think of a world in which originary interest would not exist as an inexorable element in every kind of action … If there were no originary interest, capital goods would not be devoted to immediate consumption and capital would not be consumed. On the contrary, under such an unthinkable and unimaginable state of affairs there would be no consumption at all, but only saving, accumulation of capital, and investment. Not the impossible disappearance of originary interest, but the abolition of payment of interest to the owners of capital, would result in capital consumption. The capitalists would consume their capital goods and their capital precisely because there is originary interest and present want satisfaction is preferred to later satisfaction.

Attempting to abolish interest, according to Mises, would not lead to the elimination of interest-rate lending and would instead lead to the consumption of capital stocks as savers have less of an incentive to preserve their capital when they cannot make a return on it. Banning individuals from trading financial assets based on their time preference will not eliminate their time preference, which will continue to direct their consumption and production decisions. Capital owners with a positive time preference who no longer have access to the option of lending at interest find themselves with a stronger incentive to consume their capital stock. Banning interest then leaves the borrowers worse off by not allowing them access to much-needed funds. It also leaves the lenders worse off since it forbids them from gaining a return on savings. And it hurts society overall by reducing the incentive to save and thus resulting in less capital accumulation. A society without interest lending is less productive, less innovative, and less prosperous.

From the Austrian perspective, it is difficult to argue that interest is exploitative of the borrower. There is no coercion in the loan contract, and both parties willingly choose to enter it, so there is no legal or moral justification for calling it illegal or for an outside party to attempt to violently prevent both parties from transacting.

Therefore there cannot be any question of abolishing interest by any institutions, laws, or devices of bank manipulation. He who wants to “abolish” interest will have to induce people to value an apple available in a hundred years no less than a present apple. What can be abolished by laws and decrees is merely the right of the capitalists to receive interest. But such decrees would bring about capital consumption and would very soon throw mankind back into the original state of natural poverty.

This book’s biggest break from Austrian orthodoxy is to present the case for why the interest rate may, in fact, be eliminated from a purely free market and not through official abolition or edict. As discussed in the previous section and explained in detail by Hoppe in Democracy, the process of civilization is initiated with the lowering of time preference, which results in capital accumulation, increased productivity, and improved living standards, in turn encouraging further reductions in time preference in a continuously amplifying spiral. Wars, diseases, natural disasters, increased future uncertainty, and growing uncertainty over property rights can forestall this process by causing increases in time preference and forcing people to increasingly prioritize the present at the expense of the future.

The historical empirical record supports this contention. As discussed in the previous chapter, the history of interest rates, and as detailed in the encyclopedic study on the topic by Homer and Sylla, humanity has seen a steady, long-term decline in interest rates over the past 5,000 years, interrupted by the aforementioned calamities. Hoppe summarizes the history of interest rate declines:

In fact, a tendency toward falling interest rates characterizes mankind’s suprasecular trend of development. Minimum interest rates on “normal safe loans” were around 16 percent at the beginning of Greek financial history in the sixth century B.C., and fell to 6 percent during the Hellenistic period. In Rome, minimum interest rates fell from more than 8 percent during the earliest period of the Republic to 4 percent during the first century of the Empire. In thirteenth-century Europe, the lowest interest rates on “safe” loans were 8 percent. In the fourteenth century they came down to about 5 percent. In the fifteenth century they fell to 4 percent. In the seventeenth century they went down to 3 percent. And at the end of the nineteenth century minimum interest rates had further declined to less than 2.5 percent.

Yet this trend of declining interest rates was reversed in the twentieth century. The move to fiat money likely played a major role in this shift, along with many other factors that are discussed at length in Hoppe’s Democracy. The hypothetical thought experiment worth asking here is: What would have happened to interest rates had they continued their decline in the twentieth century? What would have happened had the world remained on a gold standard, and people maintained the ability to save for the future, capital continued to become more abundant, and productivity increased? How low would interest rates go?

We may accept Mises’ contention that originary interest may never drop to zero and yet still arrive at a market interest rate of zero. The key is to consider that money, like all goods, has a carrying cost. Whatever form it takes, money requires safekeeping and storage, and this will always involve a nonzero cost and will always involve a nonzero risk of theft, loss, or ruin. The cost could be paid in many forms, such as purchasing a safe or storage facility, paying for a deposit account at a bank, or paying for insurance on the sum. Or it could be paid in the form of theft and loss, which is a risk that always exists. Some nonzero costs must be paid to hold money. For the lender, the opportunity cost of lending lies not in maintaining their nominal wealth in full. Instead, not lending means witnessing a slow decline in the value of the money due to the nonzero cost of keeping it safe.

As time preference continues to decline, and originary interest declines along with it, the implied market interest rate may eventually become lower than the carrying cost of money. In such a situation, the lender would be happy to lend at a nominal interest rate of 0% because it is a better return than simply holding the money, which would have a negative return. Rather than requiring abolition by decree, the continued process of civilization, capital accumulation, and lowering of time preference could naturally eliminate lending with interest entirely.

A decline in time preference increases the abundance of capital, and as the abundance grows, the price of capital, as interest, declines. A continuously advancing civilization would witness its time preference decline, leading to more future provision and more moral concern for future generations, which results in capital being widely abundant. As people own larger quantities of capital, the demand for borrowing declines as well. At a sufficient level of abundance, the return on lending becomes lower than the cost of carrying the money, at which point a borrower can secure a loan from the many lenders available by simply promising to pay it back in full because he would be saving the lender the cost of storage and insurance or the risk of theft and loss.

As interest rates decline with time preference, the asymmetry of the loan deal becomes increasingly unappealing to the lender. Why take on the risk of losing all the capital in exchange for such a measly return? The loan contract limits the upside benefit to the lender, but there is no force that can truly guarantee that the lender will get their money back. Risk exists, and the risk of complete and catastrophic loss can never be legislated away. In the modern fiat-based economic system, the risk of bank insolvency has been severely alleviated by being transferred to the national currency. Loans are effectively guaranteed through the central bank’s ability to monetize them and make the lenders whole on any defaults on their portfolio. This is why the FDIC is able to guarantee bank accounts in the modern world, but this is not something that you would expect to exist in the hypothetical society of this scenario, where capital accumulation and dropping time preference could not have reached some advanced stages with inflationary fiat money which the central bank can use to bail out banks, because such money would discourage saving and would not allow time preference and interest rates to decline. We would only expect to arrive at such a point with a hard monetary standard that encourages savings and allows for no bailouts for banks and no protection for lenders from bankruptcies. In such a world of lowtime preference, hard money, and no bailouts, lending for interest becomes unlikely. Lenders would get a very small return while sharing in the full downside. If they are taking the full downside, they would prefer to also get full exposure to the upside through an equity investment.

In a world of high capital abundance and negligibly low interest rates, or a world of zero nominal interest rates, people who are credit-worthy will have no problem securing capital from friends and family for emergency expenses or hardship. Lending at zero interest would save the money owner from needing to spend on storage and relieve him from taking the risk of loss. At a very low time preference, lending to a trusted borrower would thus be preferable to holding money. But for business investments, it is highly likely that the market would be predominantly based on equity. Such a world would see banking get neatly divided into two categories: investment equity banking and deposit banking.

Mises’ golden rule discussed above stipulates that commodity credit is backed fully by savings that match the full maturity of the loan. But without a lender of last resort, and at zero nominal interest rates, the rule would have an added stipulation: The lender gets a preset share of the profit of the enterprise. In other words, there would be no lender with a loan but an investor with equity.

Understanding the time preference theory of interest rates from the Austrian perspective can help explain the historical and religious case against interest. The world of the zero nominal interest rate is the world where time preference is so low that originary interest is lower than the carrying cost of money. Religious mandates against interest can be understood as prescriptions for members of the religion to lower their time preference to the point where interest lending no longer forms an attraction to them. Belief in the afterlife could be understood as conducive to the lowering of time preference. Believers expect to live in the afterlife for eternity, and so expect to face infinite rewards and punishment for their actions, leading to infinitely low discounting of future consequences.

While religions and traditions seek to impose this reality on their believers through dictates, the modern market economy, through constant capital accumulation, division of labor, technological advancement, and lowering time preference, is the tool that drives us toward this reality in practice. In other words, if the processes of the market and civilization are uninterrupted, future discounting declines to the point where market interest lending is eliminated, resulting in a system free of usury, similar to those embodied by traditional Christian and Islamic banking.

Joseph Schumpeter provides a good summary of the work of Eugene Böhm-Bawerk, the Austrian economist who did the most to develop the Austrian theory of interest rates.

[Interest] is, so to speak, the brake, or governor, which prevents individuals from exceeding the economically admissible lengthening of the period of production, and enforces provision for present wants—which, in effect, brings their pressure to the attention of entrepreneurs. And this is why it reflects the relative intensity with which in every economy future and present interests make themselves felt and thus also a people’s intelligence and moral strength—the higher these are, the lower will be the rate of interest. This is why the rate of interest mirrors the cultural level of a nation; for the higher this level, the larger will be the available stock of consumers’ goods, the longer will be the period of production, the smaller will be, according to the law of roundaboutness, the surplus return which further extension of the period of production would yield, and thus the lower will be the rate of interest. And here we have Böhm-Bawerk’s law of the decreasing rate of interest, his solution to this ancient problem which had tried the best minds of our science and found them wanting.

Whether a continued decline in time preference would bring down interest rates to a nominal zero rate is a separate question from the economic efficacy of banning interest coercively. Without the requisite low time preference, prohibiting interest lending would likely lead to more consumption, less saving and lending, and likely less investment overall. It might be the case that interest lending is the only thing that abolishes interest lending. By incentivizing saving and increasing capital accumulation, interest lending leads to a decline in time preference and interest rates, until they disappear entirely.