Table of Contents

[The] expansion of credit cannot form a substitute for capital.

– Ludwig von Mises

Circulation Credit

The previous chapter explained the working of commodity credit, which Mises defines as credit extended by banks with perfect correspondence between the quantity and maturity of the loan from the savers to the bank and from the bank to investors. In other words, commodity credit is a credit transaction where the bank is a mere intermediary facilitating the matching between savers and investors. In each commodity credit transaction, the amount of the capital invested induces an equivalent sacrifice of consumption by the owners of the savings invested, meaning interest rates reflect lender time preference. This chapter discusses credit arrangements where investment does not elicit a reduction in consumption on the part of lenders. In what Mises terms circulation credit, lending effectively creates new money.

The most common way in which circulation credit comes into existence is when financial institutions lend out money which they also promise to make available for the depositor on demand. This practice is known as fractional reserve banking. The lender, in this case, the bank’s depositor, does not have to defer consuming his deposit while it is being lent out as credit to an entrepreneur, as is the case in full reserve, maturity-matched commodity credit, where the depositor forsakes the deposit for the entire duration of the entrepreneur’s loan.

Another way in which a bank can generate circulation credit is by mismatching the maturities of its loans and deposits. If the bank only lends out credit equal to its deposits but lends at a longer maturity than it borrowed, then it is also effectively engaging in the creation of circulation credit. The loan effectively assumes the bank’s ability to find depositors willing to deposit money for a rate of return lower than the rate it is offering the entrepreneur. Circulation credit is thus generated every time the golden rule discussed in Chapter 14 is broken.

A third way in which circulation credit can be created is through the practice of rehypothecation of lending collateral—the reuse of collateral for more than one loan. If the collateral had been previously pledged to a loan, then the second loan would also not entail the deferral of consumption on the part of the lender.

In all of these three ways, credit is generated without commensurate sacrifice on the part of the lender, and it is issued as fiduciary media: Notes and bank balances that are redeemable for money but do not have an equivalent amount of money available in the bank on demand to be paid for their bearer for the entire duration of the deposit.

Money, as discussed in Chapter 10, is unique in that it is the one good that is obtained purely to be exchanged for something else. It is not consumed, like consumer goods, nor is it used in the production of other goods, as capital goods are. Since its sole purpose is to be passed on, and it performs no physical function to its owner, a claim on it, or a substitute for it, is capable of playing its role in a way that cannot be played by any substitute or claim on another consumer or capital good. A voucher for a steak cannot be eaten, a receipt for a machine cannot produce the goods that the machine produces, and an airplane ticket cannot make you fly. But a claim on money can perform the essential function of money: It can be exchanged for other goods. As Mises puts it:

The peculiar attitude of individuals toward transactions involving circulation credit is explained by the circumstance that the claims in which it is expressed can be used in every connection instead of money. He who requires money, in order to lend it, or to buy something, or to liquidate debts, or to pay taxes, is not first obliged to convert the claims to money (notes or bank balances) into money; he can also use the claims themselves directly as means of payment. For everybody they therefore are really money-substitutes; they perform the monetary function in the same way as money; they are “ready money” to him, i.e., present, not future, money.

A person who has a thousand loaves of bread at his immediate disposal will not dare to issue more than a thousand tickets each of which gives its holder the right to demand at any time the delivery of a loaf of bread. It is otherwise with money. Since nobody wants money except in order to get rid of it again … it is quite possible for claims to be employed in its stead… and it’s quite possible for these claims to pass from hand to hand without any attempt being made to enforce the right that they embody.

Because of this peculiar nature of money, monetary substitutes like fiduciary media can be used as money by people, acquired and spent as payment for goods or services, without having to be redeemed for money at the issuing bank. The banknotes or bank accounts that the bank issues as fiduciary media are themselves the medium of exchange without having to be redeemed for money. Note here that fiduciary media are distinctly different from banknotes issued with full reserve money available on demand at the bank in one very important respect: The issuance of fiduciary media involves no sacrifice on behalf of the issuing party. Therefore, when banknotes are issued with 100% money on reserve, there is no impact on the total supply of money. On the other hand, when fiduciary media are issued, they are an addition to the existing money stock. Whereas mining gold is an expensive and uncertain venture whose cost usually approximates the expected sale value of the gold, the issuance of fiduciary media increases the money supply without requiring any substantial cost on the part of the issuing financial institution. The increase in money supply naturally affects the market value of money, with substantial consequences, which the Austrian school has worked diligently to analyze over more than a century, to be discussed below.

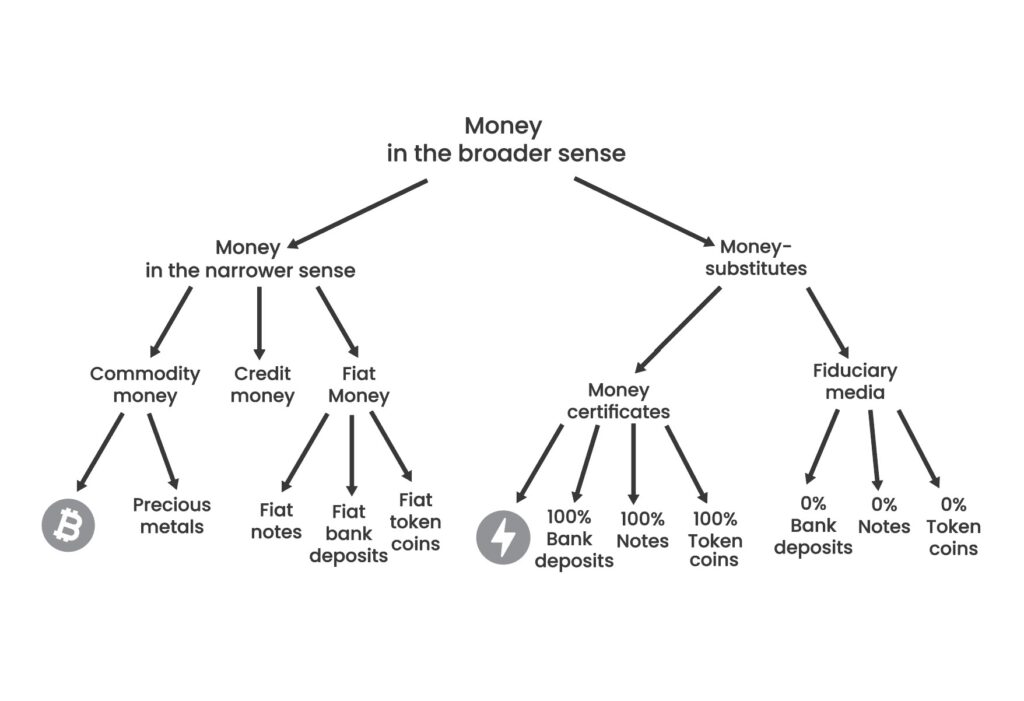

Mises’ Typology of Money

The peculiar nature of money, as a good that does not get consumed, allows money substitutes and fiduciary media to play a monetary role as well as money, which can create confusion about what exactly is referred to by the term “money.” Important distinctions exist, and it is useful to follow the typology laid out by Mises in The Theory of Money and Credit and explained in Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism, Jörg Guido Hülsmann’s intellectual biography of Mises:

Mises developed a comprehensive typology of monetary objects—that is, in Mengerian language, of all the things generally accepted as media of exchange. On the most fundamental level, he distinguished several types of “money in the narrower sense” from several types of “money surrogates” or substitutes. Money in the narrower sense is a good in its own right. In contrast, money substitutes were legal titles to money in the narrower sense. They were typically issued by banks and were redeemable in real money at the counters of the issuing bank.

In establishing this fundamental distinction between money and money titles, he applied crucial insights of Böhm-Bawerk’s pioneering work on the economics of legal entities. He stressed: “Claims are not goods; they are means of obtaining disposal over goods. This determines their whole nature and economic significance.” As his exposition in later parts of the book would show, these distinctions have great importance, both for the integration of monetary theory within the framework of Menger’s theory of value and prices, and for the analysis of the role of banking within the monetary system. At the heart of his theory of banking is a comparative analysis of the economic significance of two very different types of money substitutes. Mises observed that money substitutes could be either covered by a corresponding amount of money, in which case they were “money certificates,” or they could lack such coverage, in which case they were fiduciary media—Umlaufsmittel. Mises devotes the entire last third of his book to an analysis of the economic consequences of the use of Umlaufsmittel.

The term “money” is broadly used to refer to money and money substitutes. Mises clarifies the distinction in a way that helps explain the Austrian analysis of the business cycle. Money, in the narrower sense, can come in three forms:

Commodity money: A general medium of exchange that is also an economic good that is exchangeable with goods of the same type. It is sold on an open market with many producers and consumers. Historical examples are mainly precious metals, but more recently, bitcoin can be added as a new form of nonmetal digital commodity.

Credit money: A future financial claim on an entity that is used as a medium of exchange. What distinguishes credit money from credit is that the recipient accepts it with the intent of passing it on to another recipient, not because they want to collect the financial claim.

Fiat money: A medium of exchange accepted because of the legal decree of an authority. “The deciding factor is the stamp, and it is not the material bearing the stamp that constitutes the money, but the stamp itself.” Fiat money can take the form of paper money, bank deposits, or token coins.

Money substitutes are frequently confused for money, but they are distinct.

Money substitutes: Physical or financial instruments that are legal titles to money in the narrow sense. They can be redeemed for money on demand and are used as a medium of exchange in transactions. Money substitutes come in two forms:

Money certificates: A financial instrument or piece of paper redeemable in full for money on demand. (Value is 100% covered by the issuing authority.) Examples include a dollar bill redeemable in gold under a strict gold standard, or a bank account based on gold-backed dollars. In the realm of bitcoin, we can think of bitcoin on the lightning network as being a unique type of money certificate, because its operation is entirely in the hands of the money holder, and redemption does not depend on any third parties. Tradable receipts for bitcoin held in custody would also constitute money substitutes. And while these would have an issuing counterparty, they would still be relatively cheaply and easily redeemable for bitcoin, since access to the network is not easy to censor.

Fiduciary media: Money substitutes not backed by money holdings. When a financial institution issues money substitutes but does not have the money to redeem all substitutes, the difference is fiduciary media. This is a key term in Mises’ explanation of the business cycle, as it is precisely the creation of these media that sets in motion the boom-bust cycle. In the digital realm, these would be the equivalent of bitcoin-denominated credit issued without equivalent bitcoin backing.

According to Mises’ typology, the function of money is orthogonal to its physical form. Bank deposits take the form of money certificates when redeemable in full for money, fiduciary media when issued by banks without money backing them, or fiat money if decreed by government authority. Similarly, paper money can be a 100% money certificate, in which case it is redeemable for commodity money at face value, as in the gold standard; if it is issued by a bank and not redeemable for money, it is fiduciary media; and it is fiat money if printed by a government without redeemability. Physical coins can be made from commodity money, such as gold and silver coins; as fiduciary media if issued by a bank; as a money certificate if redeemable for money; or as fiat money if issued out of a base metal and having its value decreed by an authority independent of its metal content. By stepping away from the physical forms of the money and explaining the difference between fiduciary media and money certificates, Mises could provide an explanation of business cycles grounded in human action.

Money certificates have an equivalent sum of money in the narrow sense placed on demand for the holder at the issuing institution; their issuance does not cause an increase in the monetary media in circulation. At any point in time, when the money certificate is used for payment, the money behind it is idle in a bank vault, but effectively changes ownership. It is not possible for that narrow money to settle monetary transactions while the money certificates are in circulation. Once the money certificate is redeemed for that narrow money, the money can be spent, but the certificate cannot. Money certificates do not increase the supply of money, in the broader sense. The introduction of money substitutes in the form of fiduciary media, on the other hand, does result in an increase in the total supply of money and money substitutes in circulation.

In the past, kings would enrich themselves at the expense of their subjects by collecting coins from their subjects and minting them into new coins with some base metals mixed in to lower the content of the precious metal. By introducing base metals into the mix, the king was able to produce more coins than the amount of the precious metal he had, benefiting the king with increased purchasing power at the expense of the holders of the original currency. Over time, the price of goods would rise to reflect the drop in their metal content, and a part of everyone’s real wealth would be transferred to the king.

Although modern centralized governments no longer debase their physical coins, they nonetheless achieve something very similar by using legislation, the threat of violence, and monopoly power to force people to accept money certificates that are no longer redeemable in money as if they were money. With their redeemability suspended, money certificates become fiduciary media, which increases the overall supply of money. In the same way that kings profited by mixing base metals with precious metals, modern governments benefit by mixing fiduciary media with money. The consequences in both cases extend beyond just enriching the government at the expense of society. Introducing a cheap supplement to money does not enhance its function; it compromises it. Money is unique from other goods in that its absolute quantity does not matter to its holder, only its purchasing power. Increasing the quantity of money does not increase wealth, nor does it make money more effective; instead, it devalues existing holders’ wealth, transfers it to the recipients of the new money, and alters the prices of goods, causing economic miscalculations.

Business Cycles

Mainstream schools of economics have done a terrific job in treading carefully around the question of what causes business cycles, and for very good reason. As modern economics is largely funded by central banks to inform policy-making, it is highly unlikely to offer a successful career strategy for any person whose conclusions are not flattering to central banks. Mainstream economics research has mainly focused on discussing how to escape recessions, with very little focus on what causes recessions. It is childish impudence to attempt to solve a problem without caring to understand its causes, but fiat money allows central banks to attempt to create their own reality by financing research that focuses on finding solutions and marginalizing scholars critical of central banks. This approach was best exemplified in Krugman’s introduction to a recent reprint of Keynes’ General Theory, in which Krugman extols

Keynes’ inability to offer an explanation for the causes of the business cycle:

Rather than getting bogged down in an attempt to explain the dynamics of the business cycle—a subject that remains contentious to this day—Keynes focused on a question that could be answered. And that … most needed an answer: given that overall demand is depressed—never mind why—how can we create more employment?

Success in modern fiat academia is primarily a function of fealty to central banks rather than coherence or value of ideas, and as a result, the business cycle continues to be presented as a normal, inevitable part of the workings of a modern capitalist economy, as inevitable as night turning into day and seasons changing.

In stark contrast, the Austrian economists, and their causal realist framework for understanding the world, offer a coherent explanation for why business cycles happen and how they can be prevented. Unburdened by having to toe the central bankers’ line to secure funding, Austrians are able to offer more than the dubious Keynesian recommendations for exiting the depression: They can offer an explanation for how to avoid a depression in the first place.

The Austrian theory of the business cycle is founded on, and is a natural extension of, the Austrian theory of money and the aforementioned discussion delineating the difference between fiduciary media and money. The basic premise of the theory is the simple dictum that economic resources cannot be conjured by creating unbacked claims for them. That may sound like common sense, but for most modern economists, it is a radical concept. Governments and banks attempting to pass off unbacked claims for economic resources as equivalent to the resources or backed claims to them results in an increase in the supply of money, manifesting as an increased amount of financial capital in the hands of entrepreneurs. The increased financial capital causes entrepreneurs to engage in investments for which they do not have sufficient resources, something which only becomes apparent after they begin spending their financial capital, causing an unanticipated rise in the price of their input goods, preventing them from completing the projects.

In an economy with only commodity credit, the interest rate is determined by the interaction of individuals’ preferences for borrowing and lending at different interest rates. The preferences of these individuals for holding money, borrowing it, or lending it are determined by the quantities of money at their disposal as well as their economic conditions and desires. In a world of only commodity credit, all loans must come from a saver deciding to forgo consumption in favor of earning a positive return on lending.

The saving and consumption decisions concerning financial capital correspond directly to consumption and saving decisions for physical capital. The individuals who forgo consumption of financial capital do so by forgoing the consumption of the economic goods and services they could have bought with the financial capital. These resources that were not consumed can instead be directed toward the process of production; now, they are invested in productive enterprises.

As an obvious example, the consumer who decides to forgo eating corn allows it to be used as seed grain. As a more elaborate example from a complex economy, the consumer who decides to forgo going to a beach resort reduces the demand for staff at the resort and decreases the likelihood that the resort will purchase a new plot of land to expand. The holiday abstainer deposits the money he would have spent on the trip into a saving deposit at his bank, so the bank can now lend this money to a carmaker, which is now more likely to afford the marginal worker who was not hired by the beach resort as well as the piece of land that the resort has given up. By choosing to forgo the immediate gratification of a vacation and offering his financial assets to entrepreneurs instead, the saver has spared resources from meeting the demand for consuming holidays and allowed them to be used in the long-term production of cars.

Scarcity is the fundamental starting point of economics; money and financial institutions are tools we use to economize, increase our productivity and efficiency, and battle scarcity, but they cannot eliminate the scarcity of resources. There is a limited amount of workers, office space, equipment, computers, land, and resources, and trading them with money is the way we allocate them. As long as an economy operates on commodity credit, financial resources map onto real resources, and consumption decisions reflect real individual preferences pertaining to real-world resources, as expressed through their prices.

This process is distorted by the introduction of fiduciary media, which circulate like money but are unbacked by money. When a financial institution makes a loan without money backing it, they are issuing credit without a corresponding deferral of consumption by a consumer. The bank has issued a fiduciary note to the farmer to buy seed corn that has already been eaten. The total amount of loans issued to buy seed corn exceeds the market value of all the seed corn left from last year’s harvest at the current price. The bank has issued the car manufacturer the money to purchase land and hire workers when the holidaymaker had spent his money in the resort, allowing the resort to hire the same workers and buy the same land.

When the fiduciary media are created as a loan to entrepreneurs, it may not be clear to anyone (except Misesian economists) that this loan has created more claims than there are resources. At current corn prices, the quantity of corn which farmers plan to purchase exceeds the quantity of seed corn available on the market. But once it is planting season and the farmers go to buy the seed corn, they quickly bid the price up. Those who buy it early might manage to get all the quantity they had planned to get, but the majority will get a smaller amount. This miscalculation will be an expensive error for farmers, who will have overinvested in land, labor, and capital relative to the amount of seeds they expected to have available.

The resort and the car factory both expect their holdings of money and fiduciary media to be sufficient to secure them the land and the workers they need. But once they set out to actually hire the workers and purchase the land, the increased fiduciary media will lead to a decline in the value of money relative to the input goods, causing their prices to rise. As the landowner receives bids from the resort and the car plant, he initiates a bidding war between them and can charge a higher price. As workers find opportunities at both businesses, their wages also rise. With fiduciary media giving banks and entrepreneurs an exaggerated assessment of the reality of resources available to them by lowering interest rates, many business opportunities begin to appear profitable in entrepreneurs’ calculations when the actual resources available are not sufficient to complete them.

With the cost of the land, labor, and capital goods escalating, the two entrepreneurs’ plans are ruined. They had performed all their economic calculations based on the prices prevalent before the fiduciary media had entered circulation. But as the prices of input goods increase, their previous calculations are rendered useless. Their profitability is reduced or eliminated. Either or both of them might be liquidated, causing their work and investment to go to waste.

A business opportunity expected to offer a 4% rate of return would not attract capital from lenders when the prevalent market interest rate is 6%. But if the introduction of fiduciary media results in the interest rate declining to 3%, then it will attract capital. The same business, with the same capital stock, in the same market, goes from being unprofitable to profitable simply through the introduction of fiduciary media, which can be produced at a negligible cost. The absurdity of the situation should be obvious: Money is a good that offers no value in itself, and it is acquired to be passed on. Its quantity does not matter, only its purchasing power. Making more monetary units cannot change the economic reality of businesses whose inputs and outputs are capital and consumer goods, and if they suddenly appear profitable, then that can only be due to the defective nature of the money used.

The insolvency of these unprofitable businesses begins to become exposed when they bid up the prices of their input goods and have to revisit their profit calculations. An additional infusion of fiduciary media at this point can serve to delay the day of reckoning by providing businesses with more fiduciary media that improve their profitability, on paper, before they start spending it and prices rise again. For the boom to continue, credit creation needs to proceed at an accelerating pace. But it cannot continue forever, as the currency will collapse eventually.

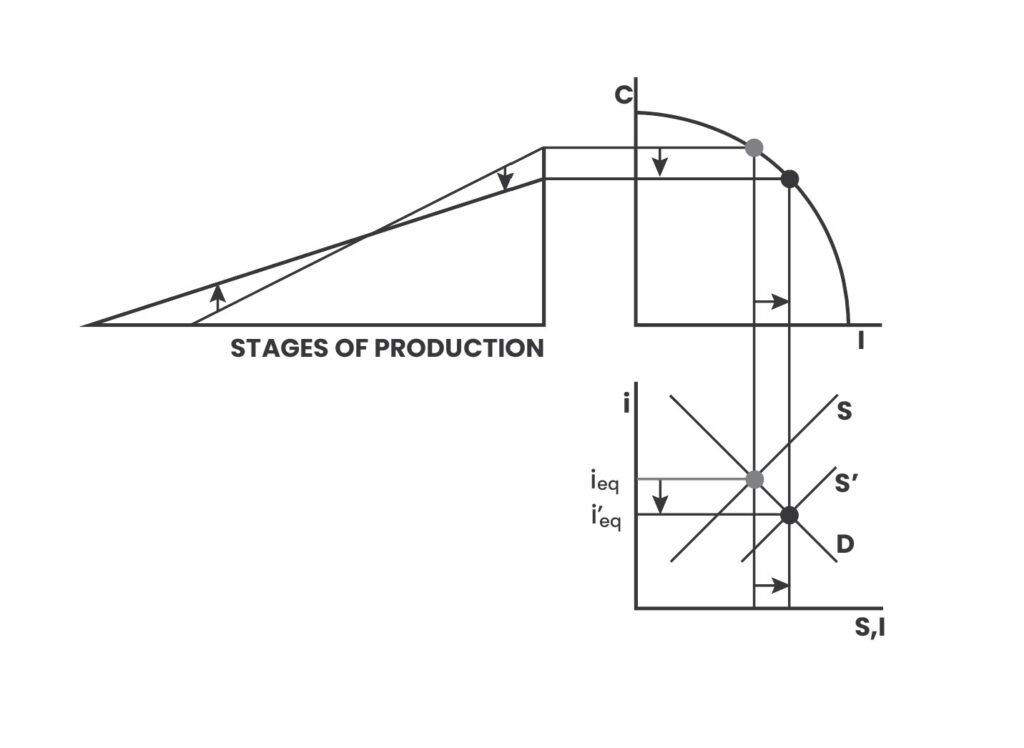

The Business Cycle Graphically

The introduction of fiduciary media into the credit market can be expressed as a shift in the supply curve for loanable funds to the right: An increase in the quantity of loanable funds available at any interest rate, as opposed to the world in which only commodity credit is available. The result is not just an increase in the amount of credit extended in the economy but also a decline in the interest rate, which lets borrowers secure debt at a lower interest rate than they would without fiduciary media. Equivalently, lenders receive a lower interest rate on their loans, which, therefore, encourages them to save less. The increased expectations of profit make matters worse by encouraging people to spend more.

This decline in interest rates is distinct from the decline brought about by the decrease in time preference leading to more abundant savings and causing the borrowing rate to decline. This decline in interest rates is created purely by monetary manipulation, not by the sacrifice of present consumption, and that is what makes it unsustainable. The introduction of fiduciary media at once leads to an increase in lending and consumption and a decline in savings, thus creating a gap between the real economic sources available to entrepreneurs and their expectations of these resources.

In Time and Money, Roger Garrison presents a graphical framework for explaining the Austrian business cycle theory and for demonstrating the difference between it and sustainable economic growth. Garrison uses the production possibilities frontier, a graph showing the maximum combinations of investment and consumption possible for an individual or society. The PPF illustrates the trade-off between consumption and investment. On the PPF, moving toward more investment requires sacrificing current consumption, and vice versa, and the slope of the curve at any point shows the price of capital in terms of consumption. Over time, if economic growth takes place, the curve will shift outward, allowing more abundant combinations of capital and consumption, whereas economic contraction will shift the curve inward, allowing lesser combinations of consumption and capital goods.

The second graph shows the market for loanable funds, where borrowers have a demand curve showing the quantity of borrowing they would undertake at all given interest rates, while lenders have a supply curve showing the quantity of lending they would provide at each price level. These two curves meet at the interest rate that equalizes the demand and supply of loans. Finally, Garrison uses the intertemporal structure of production triangles, based on Hayek’s work on business cycles. While simple, this triangle is essential in communicating the intertemporal nature of economic production, and the sequential interdependence of production stages, a point woefully missing from Keynesian analysis. The horizontal axis of the triangle represents time, in the successive stages of economic production, while the vertical axis represents the market price of economic goods through the production process, which increases with each stage of production until it reaches the final output.

The horizontal axis of the triangle represents the sum of consumer goods produced in an economy, corresponding to the x-axis in the production possibility frontier. The y-axis of the production possibility frontier represents the total quantity of investment and corresponds to the y-axis of the market for the loanable funds. The three graphs can be plotted next to each other to demonstrate the dynamics of economic growth and contraction, as well as the business cycle.

In the case of a lowering of time preference, individuals defer the consumption of final goods and invest in earlier stages of production, lengthening the stages of production, as was discussed in the examples of the fisherman in Chapter 6. When the fisherman forgoes catching a few fish in a day in order to spend time building a boat to increase his productivity, he is reducing the height of the triangle by reducing his consumption, but extending its base by lengthening the process of production. This corresponds to a move down the production possibility frontier, as consumption declines and investment increases. The same process takes place in a modern capitalist market economy as the deferral of consumption is reflected in the loanable market funds with a rightward shift in the supply curve for loanable funds, resulting in a decline in the interest rate and an increase in the quantity of loans available.

Should the investment succeed, and there is no guarantee it will, the product of the consumption will exceed the forgone initial consumption, reflected in a shift in the production possibility frontier outward, a rise in the height of the stages of production triangle, and the same level of investment maintained. As humanity has advanced in its production of fish through the stages of catching fish by hand to modern fishing boats, this process continues with more investment, consumption, and ever-longer stages of production, as shown in Figure 32. This process continues through the development of banking and the loanable funds market allowing for a larger, more specialized market in the allocation of capital, allowing savers and borrowers to transact without even having to know each other. It continues, that is, as long as the monetary instruments that are used are money certificates.

Pure 100%-backed money certificates cause no increase in the money supply. Every money certificate issued as a loan corresponds to a set quantity of a market good being held by the certificate issuer. An actual market good, money, is taken out of the hands of savers and placed at the disposal of the borrower, holding its receipt. That sacrifice is what frees up economic resources to be used in the early stages of production, rather than in consumption goods.

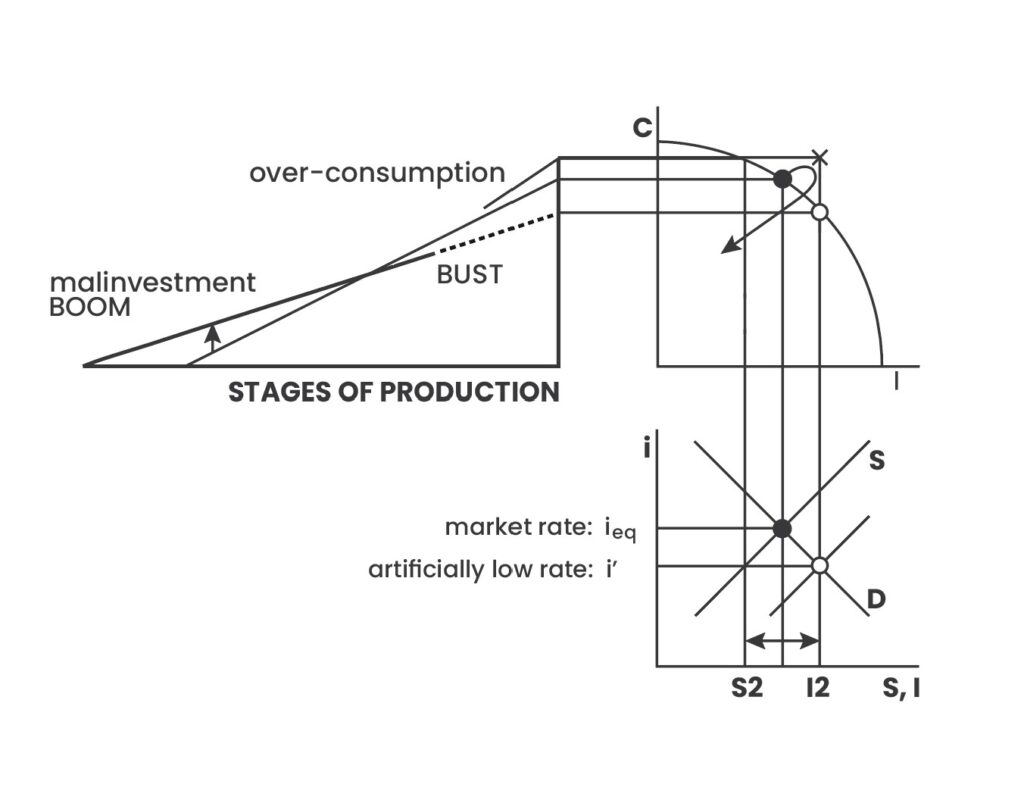

Things look very different when fiduciary media are issued instead of money certificates. Fiduciary media are issued with no corresponding money held on hand by the bank. They involve no sacrifice of economic goods on the part of anyone. Graphically, credit expansion via fiduciary media allows borrowers to attempt to lengthen the stages of production without the requisite reduction in consumption. Borrowing entrepreneurs attempt a move beyond the production possibilities frontier with a quantity of investing and consumption, which exceeds the total resources available. In the loanable funds market, it shifts the supply curve artificially by increasing the loanable funds, and in doing so, brings the interest rate down. But the reduction in the interest does not correspond to an increase in savings to finance the increased investment. On the contrary, lower interest rates encourage less saving.

The quantity of funds invested in this example, I2, is much larger than the quantity of resources saved, S2, in Figure 33. The monetary expansion not only makes entrepreneurs think they have more resources than they actually do; it also makes fewer resources available by discouraging saving and encouraging increased consumption. The difference between I2 and S2 in this graph is the capital that went to finance what Mises terms malinvestments—investments that would not have been undertaken without distortions in the capital market and whose completion is not possible once the distortions are exposed. The failure of the investment to produce the desired output results in the contraction of the production possibilities frontier, as the quantity of resources available declines. The stages of production triangle get shorter, and the stages of production contract.

In the capital market, the opportunity cost of capital is forgone consumption, and the opportunity cost of consumption is forgone capital investment. The interest rate is the price that regulates this relationship: As people demand more investments, the interest rate rises, incentivizing more savers to set aside more of their money for savings. As the interest rate drops, it incentivizes investors to engage in more investments and invest in more technologically advanced methods of production with a longer time horizon. A lower interest rate, then, allows for the engagement of longer structures of production with high productivity: Society moves from fishing with rods to fishing on large oil-powered boats.

As an economy advances and becomes increasingly sophisticated, the connection between physical capital and the loanable funds market does not change in reality, but it does get obfuscated in the minds of people. A modern economy with a central bank is built on ignoring this fundamental trade-off and assuming that banks can finance investment with new money without consumers having to forgo consumption. The link between savings and loanable funds is severed to the point where it is not even taught in economics textbooks anymore. A standard textbook portrays the supply curve for loanable funds as a straight vertical line whose magnitude is determined by policymakers. In the Keynesian alternative universe, central banks simply determine the money supply and interest rate, and it is assumed that the physical resources will materialize to fulfill the bank’s nominal monetary fantasies.

But real resources cannot be manifested by monetary policy, so artificially lowering the interest rate inevitably creates a discrepancy between savings and loanable funds. At these artificially low interest rates, businesses take on more debt to start projects than savers put aside to finance these investments. In other words, the value of consumption deferred is less than the value of the capital borrowed. Without enough consumption deferred, there will not be enough capital, land, and labor resources diverted away from consumption goods toward higher-order capital goods at the earliest stages of production. There is no free lunch, after all, and if consumers save less, there will have to be less capital available for investors.

This shortage of capital is not immediately apparent because banks and the central bank can issue enough fiduciary media for all borrowers. Creating new pieces of paper and digital entries on paper over the deficiency in savings does not magically increase society’s physical capital stock. Instead, it devalues the existing money supply and distorts prices, causing producers to begin production processes requiring more capital resources than are actually available. As more and more producers are bidding for fewer capital goods and resources than they expect there to be, the natural outcome is a rise in the price of the capital goods during the production process. This is the point when the manipulation is exposed, leading to the simultaneous collapse of several capital investments, which suddenly become unprofitable at the new capital good prices; the malinvestments. The central bank’s intervention in the capital market allows for more projects to be undertaken because of the distortion of prices that causes investors to miscalculate. In other words, central bank intervention causes malinvestment. However, the central bank’s intervention cannot increase the amount of actual capital available, so reality eventually imposes on the projects leading to their suspension. As a result, what actual capital was deployed in the project is unnecessarily wasted. The suspension of these projects at the same time causes a rise in unemployment across the economy, as a large number of people in many industries witness their business fail or have to readjust. This economy-wide simultaneous failure of overextended businesses is what is referred to as a recession.

Only with an understanding of the capital structure and how interest rate manipulation destroys the incentive for capital accumulation can one understand the causes of recessions and the swings of the business cycle. The business cycle is the logical result of the manipulation of the interest rate distorting the market for capital by making investors imagine they can attain more capital than is available with the unsound money they have been given by the banks. Contrary to Keynesian animist mythology, business cycles are not mystic phenomena caused by flagging “animal spirits” whose cause is, in turn, to be ignored as central bankers seek to try to engineer a recovery. Economic logic clearly shows how recessions are the inevitable outcome of interest rate manipulation in the same way shortages are the inevitable outcome of price ceilings. Keynesian economics creates the business cycle and then sells Keynesianism as the cure.

An analogy can be borrowed from Mises’ work (and embellished) to illustrate the point: Imagine the capital stock of a society as building bricks and the central bank as a contractor responsible for assembling them to build houses. Each house requires 10,000 bricks to build, and the developer is looking for a contractor who will be able to build 100 houses, requiring a total of 1 million bricks. But a Keynesian contractor, eager to win the contract, realizes his chances of winning the contract will be enhanced if he can submit an offer promising to build 120 of the same house while only requiring 800,000 bricks. This is the equivalent of the interest rate manipulation: It reduces the supply of capital while increasing the demand for it. In reality, 120 houses will require 1.2 million bricks, but there are only 800,000 available. The 800,000 bricks are sufficient to begin the construction of the 120 houses, but they are not sufficient to complete them. As the construction begins, the developer is very happy to see 20% more houses for 80% of the cost, thanks to the wonders of Keynesian engineering, which leads him to spend 20% of the cost saved on buying a new yacht.

But the ruse cannot last as it will eventually become apparent that the houses cannot be completed and the construction must come to a halt. Not only has the contractor failed to deliver 120 houses, but he will also have failed to deliver any houses whatsoever, and instead, he has left the developer with 120 unfinished houses, effectively useless piles of bricks with no roofs. The contractor’s ruse reduced the capital spent by the developer and resulted in the construction of fewer houses than would have been possible with accurate price signals. The developer would have had 100 houses if he had gone with an honest contractor. By going with a Keynesian contractor who distorts the numbers, the developer continues to waste his capital for as long as the capital is being allocated according to a plan with no basis in reality. If the contractor realizes the mistake early on, the capital wasted on starting 120 houses might be very little, and a new contractor will be able to take the remaining bricks and use them to produce 90 houses. If the developer remains ignorant of the reality until the capital runs out, he will end up with 120 unfinished homes that are worthless, as nobody will pay to live in a roofless house.

When the central bank manipulates the interest rate lower than the market clearing price by directing banks to create more money by lending, they are at once reducing the amount of savings available in society and increasing the quantity demanded by borrowers while also directing the borrowed capital toward projects which cannot be completed. Whenever a government has started on the path of inflating the money supply, there is no escaping the negative consequences. If the central bank stops the inflation, interest rates rise and a recession follows, as many of the projects that were started are exposed as unprofitable and have to be abandoned, exposing the misallocation of resources and capital. If the central bank were to continue its inflationary process indefinitely, it would just increase the scale of misallocations in the economy, wasting even more capital and making the inevitable recession even more painful. There is no escape from paying a hefty bill for the supposed free lunch that Keynesian cranks foisted upon us.

Friedrich Hayek likened credit expansion to catching a tiger by the tail. Once you have held on to the tiger’s tail, he begins to run, and there are no good options moving forward.

We now have a tiger by the tail: how long can this inflation continue? If the tiger (of inflation) is freed he will eat us up; yet if he runs faster and faster while we desperately hold on, we are still finished! I’m glad I won’t be here to see the final outcome.

Capital Market Central Planning

Fiduciary media are financial products that could emerge naturally on a free market, but it is entirely unlikely they would survive for long. They could emerge on the market due to the unique nature of money as a good whose only purpose is to be exchanged for something else, which makes a claim on money seemingly as good as money since both can be exchanged for goods. Fiduciary media would not be likely to survive long on a free market, however, because their existence leaves their issuer at risk of insolvency should a certain percentage of their creditors seek to redeem their fiduciary media for money.

Under the gold standard, fiduciary media were widely used, but they led to periodic financial crises in which large amounts would be wiped out or discounted heavily. Fiduciary media could survive under a gold standard since a significant amount of overall monetary holdings would remain in the bank at all times, and many money holders preferred to keep their money in the bank, where it could have been used for settling payments at a far lower cost than moving physical gold. Paying in person with physical gold was prohibitively expensive outside of one’s whereabouts, and the advancement of transportation and telecommunication technology meant more and more of an individual’s transactions took place across long distances, so an increasingly large percentage of gold cash balances had to stay in banks to increase its salability across space. Any time a holder of a banknote chose to cash it out for physical gold, they forwent a large decrease in the salability of their money across space. This allowed banks a margin of error with issuing fiduciary media, knowing not all their customers would ask for redemption at the same time.

But this margin of safety is self-defeating: The more secure the bank is, the more fiduciary media it issues, then the less secure it becomes and the more susceptible it is to a bank run. These bank runs would come periodically and would be disastrous for many people involved. A free market in money and banking would have likely continued to wipe out banks and customers engaging in the issuance of unbacked credit until such a practice was eliminated. The marginal cost of producing fiduciary media for a bank approaches zero, and a free market in banking would supply fiduciary media until their price is equal to their cost of production, which effectively means the fiduciary media will be discounted until they become money certificates, with their face value equal to whatever backing exists to redeem them.

In the nineteenth-century United States, monopoly state banking licenses prevented free-market competition from doing away with fiduciary media. So long as entry into the banking industry was restricted, it was profitable for the incumbents to produce fiduciary media, even though these media would still have caused periodic crises and collapses. Periodic government interventions in the banking system and the establishment of the first and second U.S. central banks would help protect banks from the free-market consequences of unbacked credit expansion. In 1907, a large financial crisis crystallized the attention of financial industry leaders on the need to establish a third monopoly central bank to stand ready to bail out banking institutions in times of financial crises. In 1913, the U.S. Federal Reserve Act was passed, and the new central bank was given the inherently contradictory dual mandate of protecting the value of the currency while also rescuing banks from financial crises, which can only be achieved by debauching the currency. Over the past century, the cost of protecting unbacked credit from just market assessment has been the constant debasement of the currency. Whereas in the nineteenth century, fiduciary media issuance would cause financial crises and distress, this would be relatively contained and restricted to people willingly involved with these financial institutions. Gold holders had nothing to fear since the market price of their money was largely unaffected. In the twentieth century, financial crises were almost always ameliorated and resolved through the devaluation of the currency held by people uninvolved with insolvent institutions.

Rather than offering a way to increase investment and productivity, credit expansion unbacked by real savings has proven to be a recipe for financial crises in the nineteenth century and the cause of the destruction of sound money in the twentieth century. In order to protect financial institutions from the consequences of unbacked lending, a socialist central-planning board was placed in charge of the market for money and capital, the most important market and the one integral part of all markets.

While most people imagine that socialist societies are a thing of the past and that market systems rule capitalist economies, the reality is that a capitalist system cannot function without a free market in capital, where the price of capital emerges through the interaction of supply and demand and the decisions of capitalists are driven by accurate price signals. Recessions and financial crises are best understood as the failures of capital markets when central planning restricts monetary freedom. Monopoly central banks’ meddling in the capital market is the root of recessions and financial crises. Yet the majority of politicians, journalists, and academics invariably blame these centrally planned disasters on capitalism.

The form of failure that capital market central planning takes is the boomand-bust cycle, as explained in Austrian business cycle theory. It is thus no wonder that this dysfunction is treated as a normal part of market economies because, after all, in the minds of modern economists, a central bank controlling interest rates is a normal part of a modern market economy. But a central bank is as normal a part of a capital market as a monopoly potato bureau is a normal part of potato markets.

Austrian authors have meticulously documented monetary history in some highly recommended reads, which use Austrian theory to illuminate our understanding of history, which is so often blinded by government historians’ need to embellish the actions of the state and its monetary disasters. Hayek’s Monetary Nationalism and International Stability, Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression and A History of Money and Banking in the United States, and Ferdinand Lips’ Gold Wars are particularly good examples. This history points to some unfortunate, disastrous, and regular patterns in the development of modern banking and governments.

In the short term, governments and central bank administrators believe they can achieve their goals by debasing money to finance credit creation and spending on important causes. Governments may believe they are boosting the economy, or protecting people from the consequences of free markets, but by debasing the money to achieve these goals, they are creating malinvestments and sowing the seeds of great long-term harm. Attempting to rescue the economy from the inevitable resulting crises results in further credit creation and bailouts encouraging irresponsible behavior, rewarding the wasteful and punishing the prudent. In that way, central banks all but ensure the boom-and-bust cycle will become a permanent fixture of an economy, and their power over the market grows. Over time, the result is the destruction of capital, money, the ability to save, and the division of labor itself. Placing money in the hands of government monopoly is far from a panacea; it is destroying the foundations on which human society and modern capitalist civilization are built.