Table of Contents

The market economy is the social system of the division of labor under private ownership of the means of production. Everybody acts on his own behalf; but everybody’s actions aim at the satisfaction of other people’s needs as well as at the satisfaction of his own. Everybody in acting serves his fellow citizens. Everybody, on the other hand, is served by his fellow citizens. Everybody is both a means and an end in himself, an ultimate end for himself and a means to other people in their endeavors to attain their own ends.

– Ludwig von Mises

Money allows for specialization and the division of labor, which in turn encourages the emergence and growth of a market economy. A market economy is a social order in which people are able to cooperate in very large numbers on economic production, providing goods and services for one another to the benefit of all involved, voluntarily, without a coercive authority dictating and coordinating their actions.

To appreciate the enormous benefits of a market economy, imagine the impact on your life, in terms of your chances of survival, the quantity of time you have, and the quality of your time, if you were to live in isolation from the world or in a small tribe with no trade with the rest of the world. The range of goods available to you would be tiny, and your ability to protect yourself from nature would be very limited. Specializing in, say, welding or painting would be impossible because all your waking hours would be spent economizing the basest of tasks required to avoid starving or freezing to death. People are drawn to partake in the market economy because of the compelling and unrivaled benefits it provides to participants, as opposed to the desperately miserable alternatives.

In a market economy, individuals do not need to think about their own production with regard to their own consumption needs. The growing specialization and division of labor allow each individual to focus on the avenues of production that offer him the best returns for his effort in monetary terms, which would then allow him to maximize the goods he acquires for his own needs. Rather than produce for himself the goods he needs, a participant in the market economy specializes in providing the goods he produces best for other people and relies on other people for procuring the goods he himself needs. Profoundly, the capitalist market system makes people specialize in what they do best and focus on how to provide value for others, rather than focusing on what they value. People choose to serve others in a capitalist system because it is far more productive and efficient than working for yourself alone in isolation from the division of labor.

The underrated marvel of the market economy is how it enables cooperation between people without the need for coercion, central direction, or social ties to compel them. What coordinates the activities of producers in the division of labor is their ability to perform economic calculations on the best uses of the resources they own, using one denominator, the monetary price. As an economy grows to an extent where all economic goods can be purchased and sold on a market in exchange for one good, economic actors can calculate the different costs and benefits of any course of action and compare them to their own preferences and to the available alternatives. The freedom of all to express their preferences through economic actions gives everyone the self-interested incentive to act in ways that satisfy the desires of others. It is not authority or violence that commands people’s actions, but their desire to meet their own needs, according to the calculations they perform based on prices that express the preferences of other participants in the market. As Mises put it:

Market exchange and monetary calculation are inseparably linked together. A market in which there is direct exchange only is merely an imaginary construction. On the other hand, money and monetary calculation are conditioned by the existence of the market.

When the market price of all goods is measured in terms of one good, individuals are able to compare prices, both to other prices and their own subjective valuations, and make consumption and production decisions. Value, as discussed in the first chapter of the book, is subjective. It cannot be measured objectively, as there is no constant unit against which it can be measured. But when an individual makes his own choices in a market, he is weighing economic choices against his subjective valuations. The values may not be measurable with a constant unit, but they are comparable to one constant frame of reference: the individual making the valuation. Knowing his own preferences allows man to order different options according to a scale of preference. While we cannot attach cardinal numerical valuations to different options, we can order them in terms of preference. This chapter explains a mathematical graphic model for thinking about how these decisions are made in the context of a market economy.

Consumer Good Markets

Economic actors acquire consumer goods to satisfy their needs and wants, and they pay a monetary price in exchange for them. Individuals perform economic calculations to weigh the market price of goods as opposed to the valuation they personally place on these goods. As prices change, the quantity of a good they would purchase changes naturally. Valuation is subjective and ordinal, not cardinal. In other words, individuals value goods by ranking them in relation to other goods. People do not attach a numerical valuation to objects, they instead compare their utility and order them in terms of their preference, as evidenced by the market choices they make.

We can think of this economic choice as being achieved through individuals producing a value scale: A ranking of goods in terms of individual preference. For any particular good, the value scale reflects the valuation of certain quantities of the good compared to monetary units.

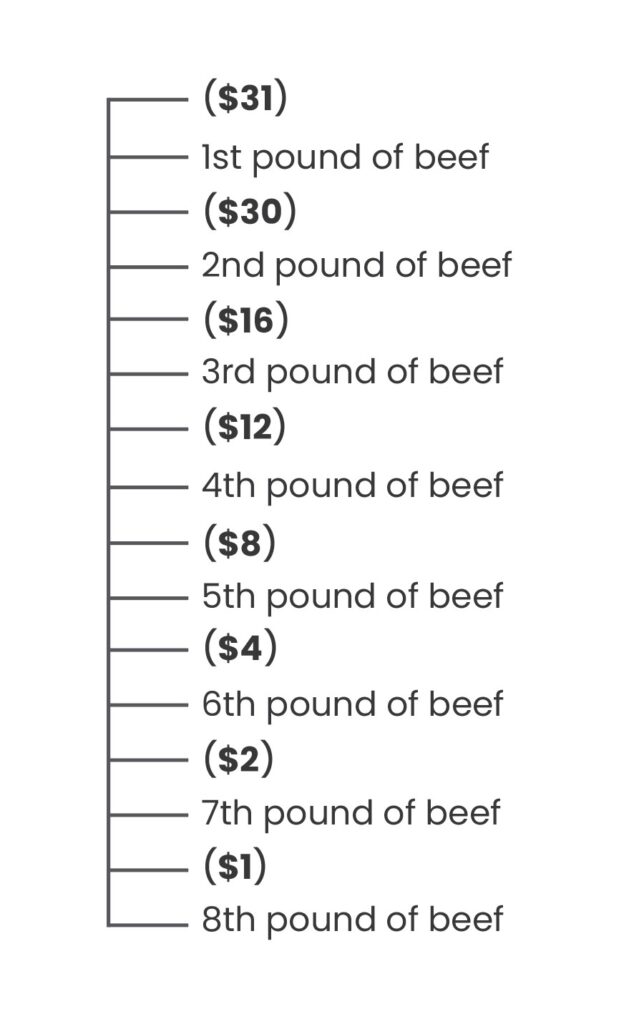

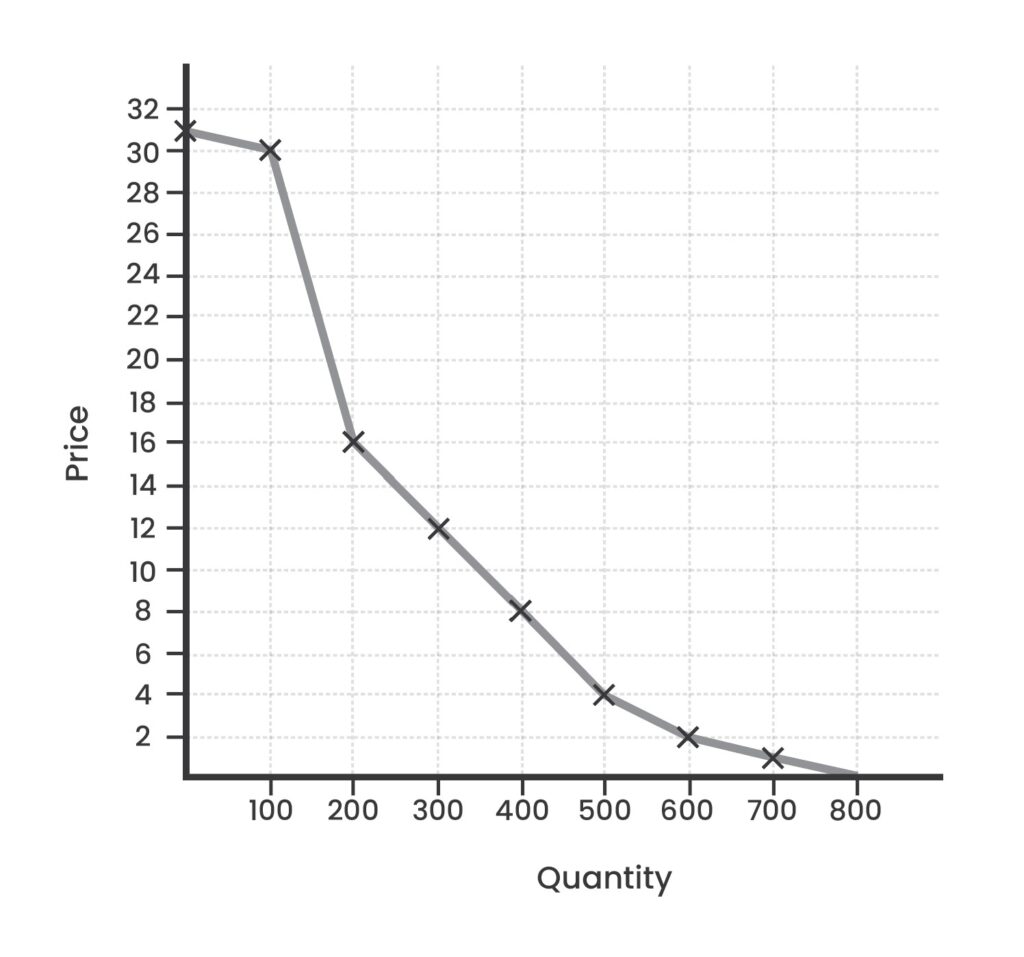

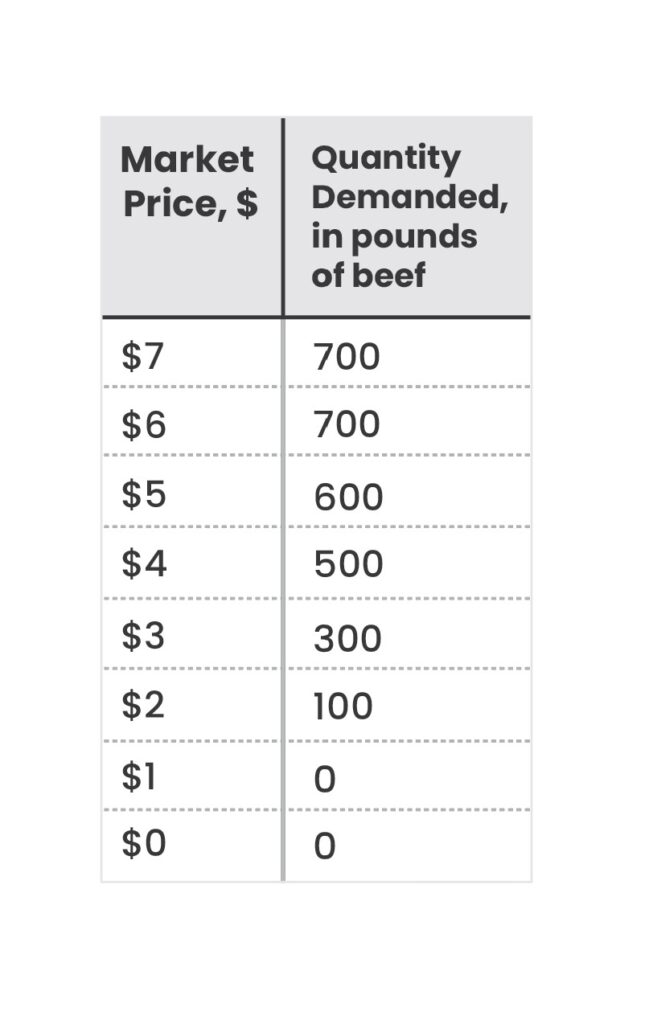

Take as an example a man considering his daily demand for beef. The first pound of beef he eats in a day is extremely valuable for him, and he would be willing to pay a significant price to ensure that he can get it because without it, he would be malnourished and hungry. Given his own income, wealth, and preferences for beef, he would not be willing to pay $31 for a pound of beef. But he would be willing to pay $30 for the first pound of beef of the day, which means he values the first pound of beef more than $30. Once he has secured that pound, the second pound of beef is slightly less valuable to him, and the cash balance he has left becomes more valuable to him, having been reduced by paying for one pound already. At that point, he would be willing to pay up to $16 for the second pound of beef since he values it a little more than this amount. When considering whether to buy a third pound of beef, he would pay the cost only if the price were $12 or lower. And he would buy the fourth only if the price were $8 or lower. As the price declines, he demands more units, and at a prevalent market price of $4, he would consume his fifth pound of beef per day. If the price of beef were $2, he would consume 6 pounds in a day. If the price of beef were $1, he would consume 7 pounds in a day. At a price of $0, in a world in which he is offered unlimited beef for free, the man would consume only 8 pounds of beef in

a day.

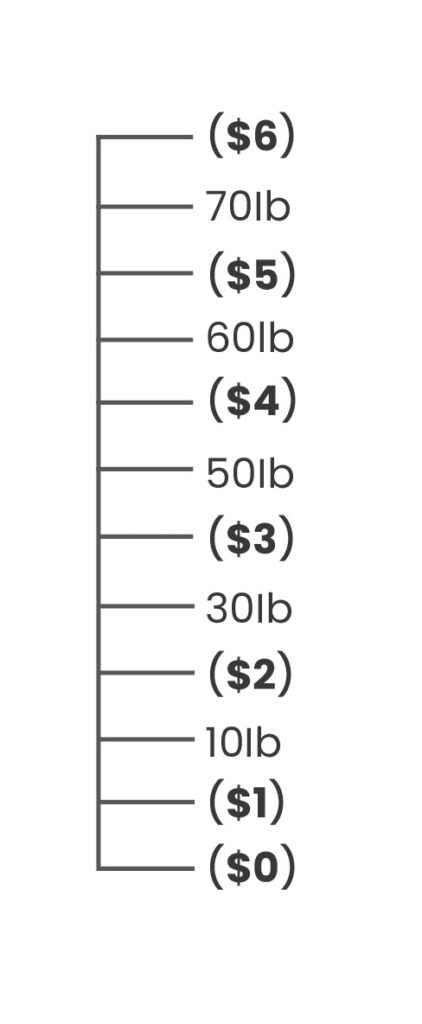

Based on these subjective decisions, the man can rank his valuation of different quantities of beef and dollars, ordinally:

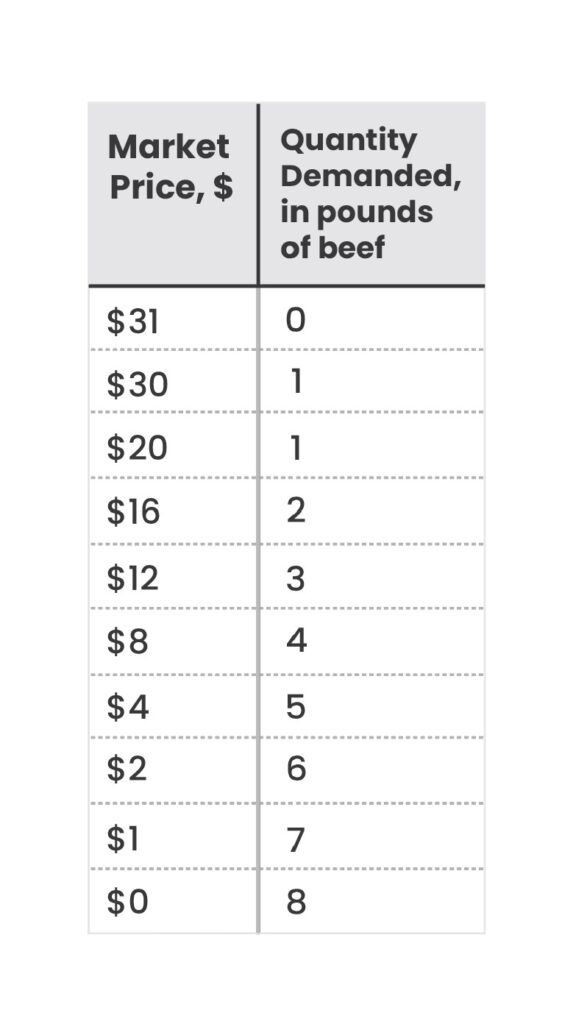

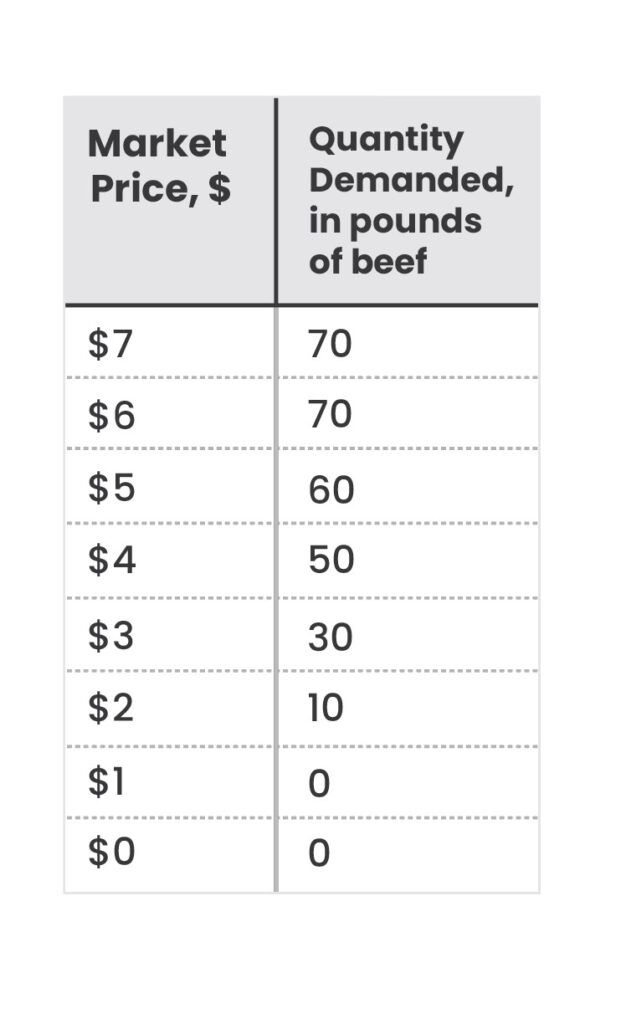

The ordinal ranking of goods is a conceptual tool economists use to understand the thought process that goes into making purchasing decisions. The ordinal value scale can be understood as the subconscious foundation of that choice, but in the real world, the buyer is confronted only with one price, and he will decide the quantity he will buy at that price. We can deduce the quantities he would purchase at each price. From this ordinal ranking of beef against monetary units, it is possible to derive a demand schedule: A table that shows the quantity demanded at each price level.

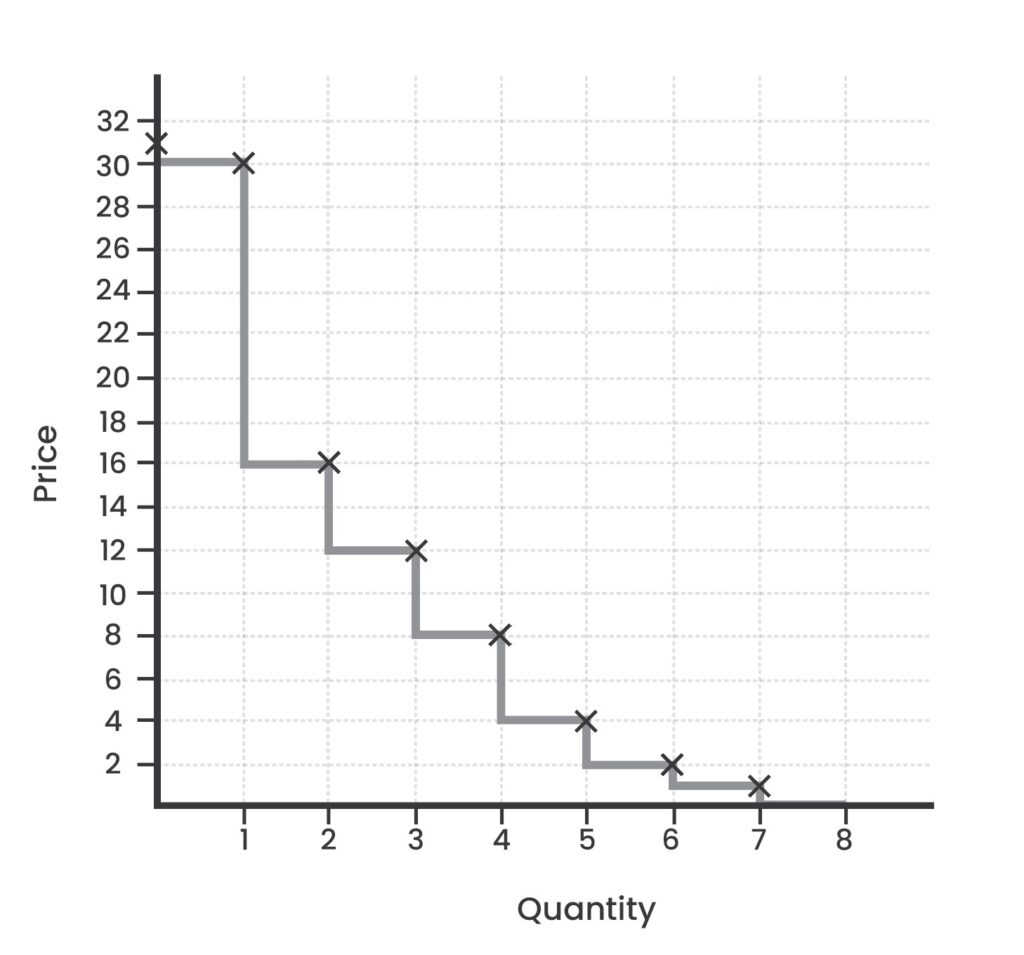

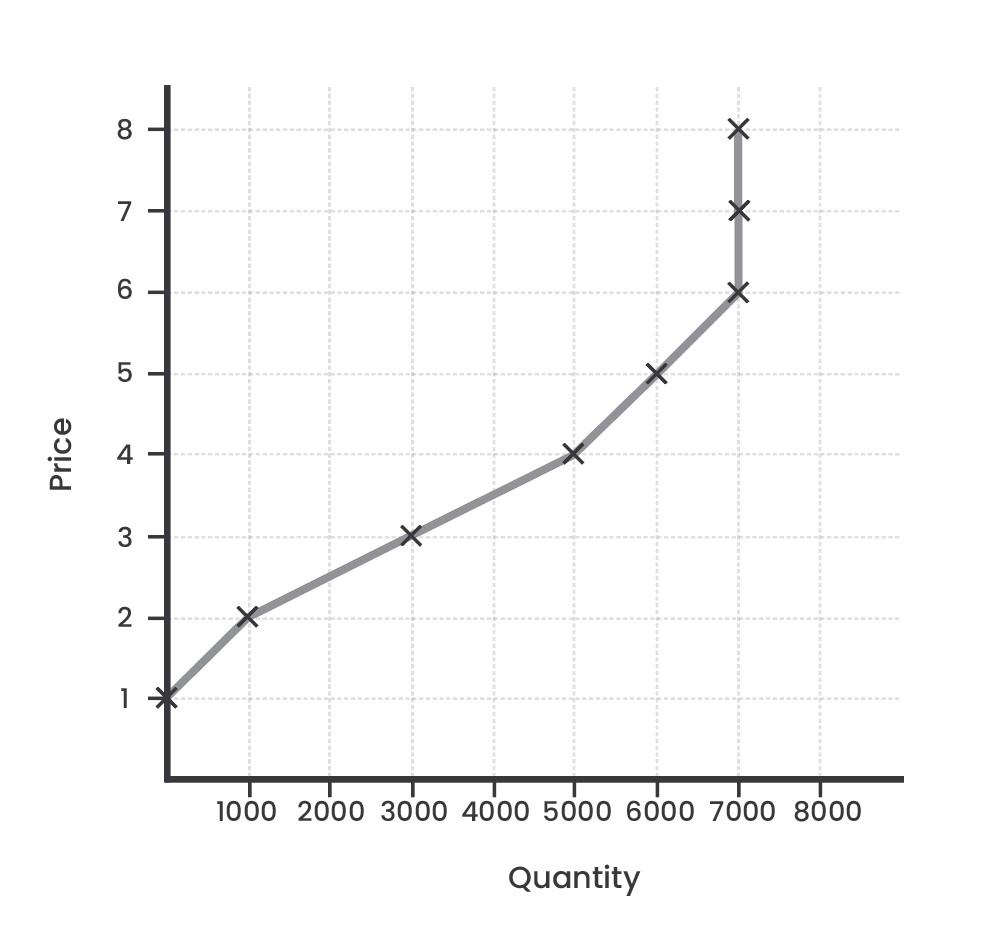

This demand schedule can then be presented in graphical form to visualize the quantities demanded at each level. In economics, the convention has it that the quantity is plotted on the x-axis, while the price is plotted on the y-axis. This can appear counterintuitive to anyone coming from the natural sciences, since convention there is that the dependent variable is placed on the y-axis, whereas the independent variable is placed on the x-axis. Nonetheless, in economics, the quantity demanded is a function of the price.

As explained in Chapter 2, individuals value the first unit of a good more than all other subsequent units, and the valuation declines the more units they acquire. On the other hand, spending money on the units causes the buyer’s cash balance to decline, raising the marginal utility of money. With each increased unit of the good, the marginal price that the buyer would pay declines, which implies the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded declines. Demand curves always slope downward, or are vertical, but they cannot slope upward because the quantity demanded of a good cannot increase as the price increases.

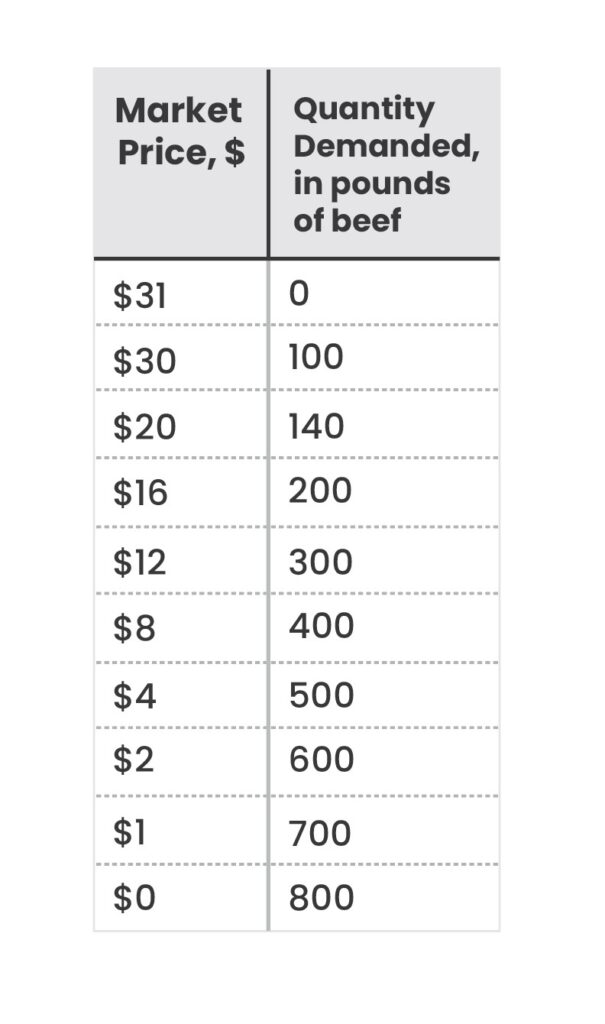

This analysis was conducted for one individual, but it can be applied to all individuals in a market for a good. By adding the quantities demanded for each person at each price point, we can get a curve showing the total market demand at a particular point. For simplicity, let us assume that this market is made up of 100 consumers whose average is represented by the consumer discussed above, so that the quantity demanded is 100 times the values shown in the individual demand schedule. Because the numbers grow, and individual preferences vary slightly, we will also get a more granular distribution of quantities, rather than the clear-cut step function of the individual demand curve shown above.

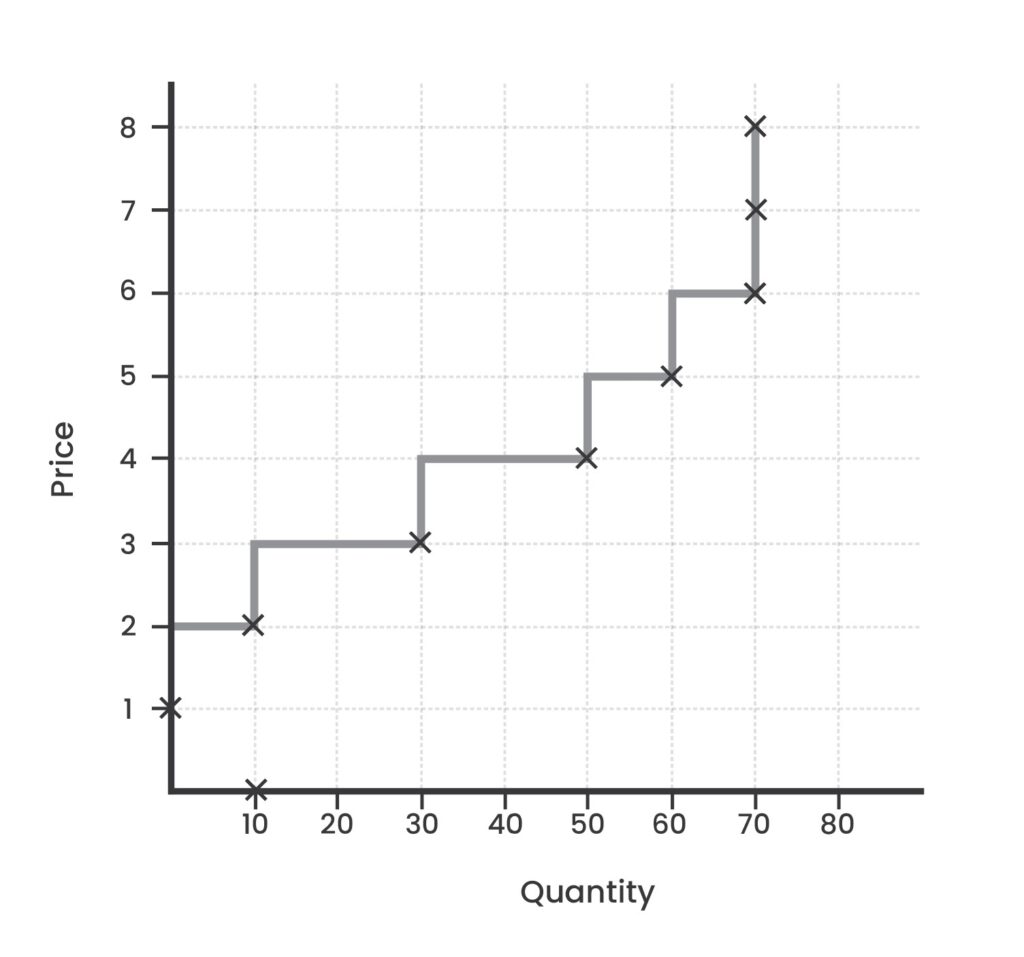

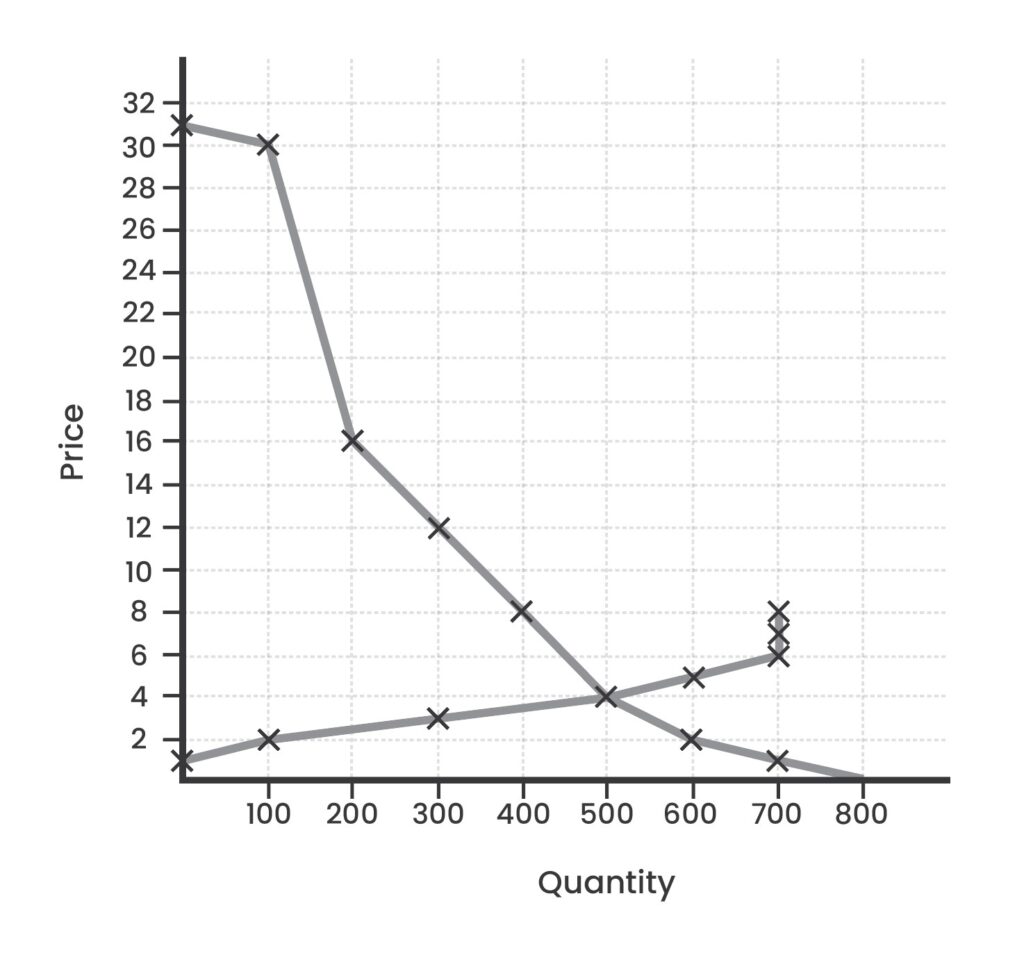

On the supply side, producers perform a similar mental calculus with the goods they sell. Producers’ personal preferences can be expressed as a value scale that results in an ordinal ranking of quantities of the good against different quantities of money. In a market economy where producers produce to sell, and not for their own consumption, the cost of producing the goods is the prime determinant of the ordinal producer’s ordinal value scale. The higher the market price, the higher the expected return on sales, and the more resources that can be dedicated to producing more units of the final good.

As an illustrative example, consider a butcher selling beef to the consumers above. At a price of $0 or $1 per pound, the butcher will not sell any beef, as the price does not cover the cost of providing the beef, so he prefers to either keep his beef for himself or not butcher it at all. Only at a price of $2/lb is the butcher able to begin producing, and he can provide 10 pounds of beef, a small quantity he can provide with a basic set up he can afford to operate at that low price by procuring beef from the closest farms. At a price of $3/lb, he can hire a worker and provide 30 lb. If he can expect a price of $4 per pound of beef, he can hire another worker and provide 50 lb. At a price of $5, he can provide 60 lb of beef, and at $6, he can provide 70 lb of beef, which is the maximum he is able to provide. Further increases in price cannot increase his capacity past 70 lb of beef.

This valuation scale can also be converted to a demand schedule and curve, which show the quantity the producer would supply at every price level.

The law of supply states that as the price goes up, owners of an economic good become more willing and able to sell larger quantities. As a consequence, supply curves slope upward only. This can be understood with reference to individuals’ preference for owning goods, which decreases as the price they can get in return for their money increases. It can also be understood for the case of producers on the market; increased prices increase producers’ incentive to produce more and allow greater investment in securing raw materials and laborers, resulting in larger quantities supplied.

For a good with several producers, the supply schedules and curves of all producers can be aggregated into one market supply curve. The market demand curve shows the quantity that would be produced by all producers of the good at every given price level. For this example, let us assume there are ten producers and that the above example represents their average.

Equilibrium

At a price of zero, the quantity demanded is very large, while the quantity supplied is likely zero. As the price rises from zero, the quantity demanded decreases, while the quantity supplied increases. There is, at most, one price point at which the quantities demanded and supplied are equal, and that is referred to as the equilibrium price. This price point functions like a magnet to buyers and sellers, drawing them to always transact around it.

If prices are set higher than the equilibrium price, the sellers supply a quantity of the good larger than the quantity demanded by the buyers, resulting in a surplus. Sellers would naturally want to drop the price in order to encourage more buyers to buy their surplus goods, drawing the price to the equilibrium price. If, on the other hand, prices were set lower than the equilibrium price, consumers would demand a quantity larger than that provided by sellers, resulting in a shortage, which would incentivize sellers to raise their prices to ration the supply and maximize their profits. They can keep raising their prices until the equilibrium price, after which point, any further price increases would result in fewer buyers and a surplus. The dynamics of the market would always draw the price to the equilibrium price.

We can see the market equilibrium from the previous example by superimposing the supply and demand curves on one chart. Because the demand curve slopes downward, while the supply curve only rises, the 2 curves can only intersect at 1 point, if at all. In this market, the ten producers of beef would produce 400 pounds of beef to sell at a price of $4, and the 100 consumers would buy all these at a price of $4. There are no surpluses or shortages. As changes occur in individual value scales, the supply and demand curves will adjust to reflect these changes, and the quilibrium will shift, but it will continue to attract buyers and sellers.

All participants in the market act in ways that benefit themselves. They agree to take part in these transactions because they expect to benefit, and they choose which transactions to take part in because they think they are getting the best deal possible. The concept of equilibrium is very powerful for understanding how voluntary market interactions arrive at prices without coercive authority or decree. Yet it is more productive to think of markets as equilibrating processes, rather than to imagine that markets arrive at a rigid set of equilibrium prices for all goods. The world of human action is constantly changing, and supply and demand conditions are constantly being affected by various factors. As their own individual conditions change, the realities of the market change. Equilibrium, then, is not a final state at which markets arrive. Instead, markets are constant processes of discovery where supply and demand conditions are always equilibrating toward the prices that help produce the most value for the actors involved.

Changes in price result in a change in the quantity that individuals demand, graphically expressed as movement along their demand curves. But changes in other factors pertaining to demand cause the reformulation of the pricedemand relationship, with a new quantity demanded at each price, and thus a shift in the entire demand curve. Factors that could shift the demand curve include changing preferences, changes in income and wealth, or changing prices of other goods and services. If the buyer’s income or wealth increases, they are likely to demand more of most goods and the demand curves for goods would shift to the right, increasing the quantity demanded at all price levels. But for inferior goods, an increase in income or wealth would cause the opposite effect, reducing the quantity demanded at all price levels, shifting the demand curve to the left, as people are able to afford superior alternatives. Beans are an example of such an inferior good: As incomes rise around the world, people are likely to reduce their demand for beans and increase their demand for beef. A good’s demand curve can also be affected by changes in the prices of other goods. A rise in the price of a good causes the quantity demanded to decline and causes the quantity demanded of a good complementary to it to decline at all price points, shifting its demand curve to the left. If that same good declines in price, the quantity demanded will rise, while the quantity demanded of the complementary good will rise at all price levels, shifting its demand curve to the right. The opposite holds when the good is a substitute good.

Other than price, market supply is also affected by the cost of production and the prices of related products that can be produced with the same factors of production. As producers’ costs of production rise, they are able to supply lower quantities of their product at each price level, shifting the supply cost to the left. On the other hand, if the producer realizes he is able to make better returns by shifting his productive factors to producing another good whose price is rising, that would shift the supply curve for the original good to the left, reducing the quantity supplied at all price levels.

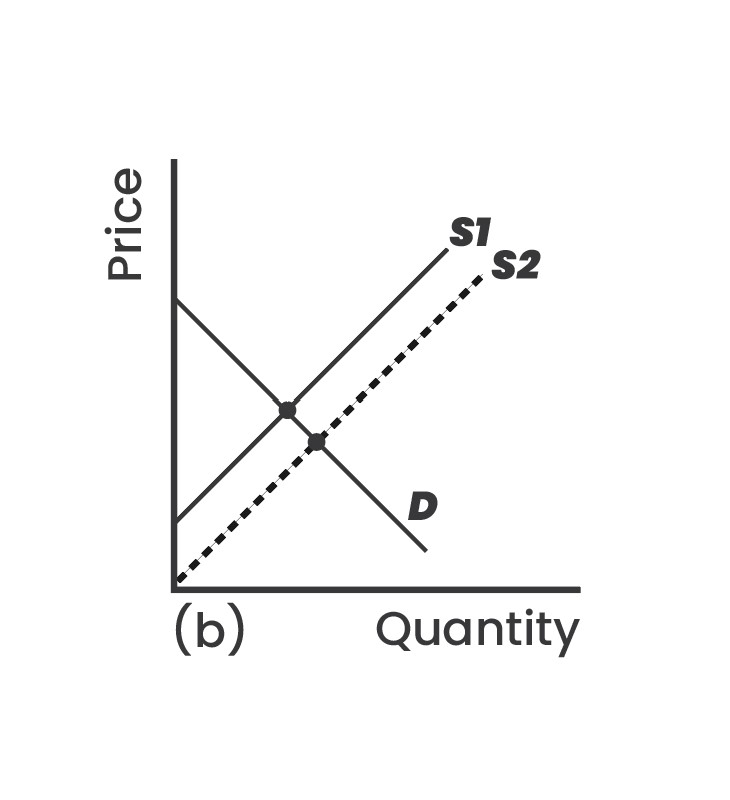

This graphical framework helps explain how a free market would react to changes in supply and demand conditions over time. In industries where technological innovation allows producers to produce increasing quantities of a good at a given price, the result is a shift in the market supply curve to the right. The consequence of this shift is that the equilibrium price will drop, and the quantity sold will increase. This trend can be seen in the high-tech industry, where prices and quantities are constantly increasing due to increased productivity and technological innovation.

Graphically, this can be illustrated with the shift from S1 to S2 in Figure 27.

If the opposite were to happen, and a supply chain problem negatively affected the production of the good, producers would be able to provide a smaller quantity of the good at any given price level, effectively shifting the supply curve to the left. In this situation, the new equilibrium with the demand curve would emerge at a higher price and a lower quantity. A natural disaster is an extreme example of this, in which the available quantities of a good decline enormously, while the prices rise. This is reflected graphically in the shift from S2 to S1 in Figure 27.

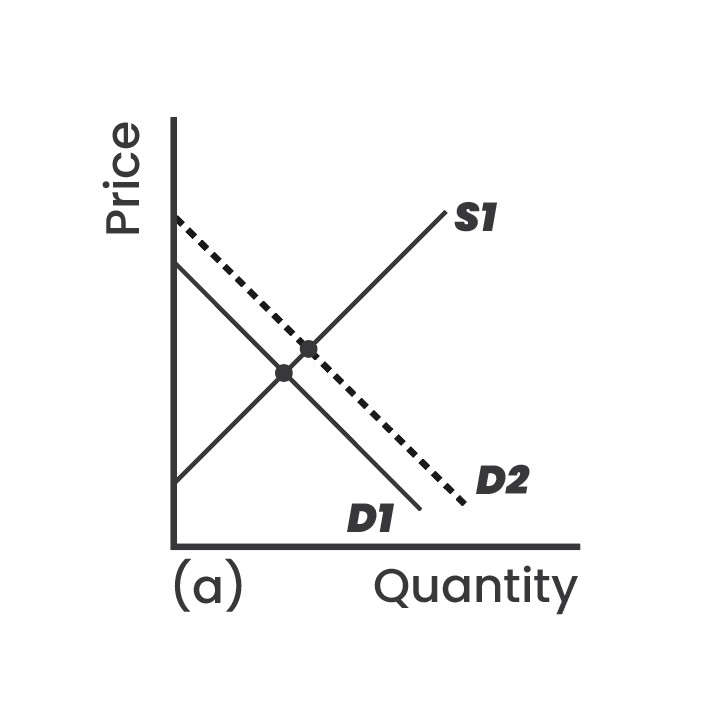

We can apply the same analysis to shifts in the demand curve. Factors that cause increases in consumer demand at all prices, such as an increased consumer preference for the good at all prices, or an increase in the price of substitute goods, or a drop in the price of complementary goods, would cause the demand curve to shift to the right, graphically illustrated as the move from curve D1 to curve D2 in Figure 28. A decrease in consumer demand for the good at all prices, or an increase in the price of complementary goods, or a drop in the price of a substitute good would shift the demand curve to the left. Graphically, this is shown by the move from curve D2 to D1 in Figure 28.

Producer Good Markets

When making their production decisions, producers also base their decisions on the utility provided to them by different courses of action. The difference between consumer choice and producer choice lies in the fact that the producers are not deriving personal utility from the factors that they employ; they are purely employing them in order to maximize the monetary profit they can achieve from their business. Consumer sovereignty means the producer is basing all his business decisions on the wants and needs of the consumer.

The production process consists of turning production factors into final goods and services to be sold to consumers. The quantity of each factor of production employed is determined by comparing its cost to the revenue it contributes to business operations, at the margin. Each additional unit of labor or capital employed in production will result in a marginal increase in the quantity of final goods produced. Employers will keep hiring factors of production as long as the expected marginal revenue of the employed factor exceeds the cost of employing it. The prices of these factors of production will in turn be determined by how well they satisfy consumer demand. If hiring an additional worker for a day is expected to add $10 of revenue to a business, that business will only hire an additional worker if their wage demand is less than $10 per day. If an entrepreneur is considering buying a machine that costs $1,000, he will buy it only if the expected discounted marginal value product it produces over its lifetime is greater than $1,000. Ultimately, therefore, it is the consumers’ valuation of final goods that gives value to factors of production. The function of the entrepreneur is to make judgments about the future desires of consumers, invest in the factors of production before production has taken place, and assume the risk that he iswrong about what consumers will value after production.

It is futile to complain about wages or returns on capital. These are vital signals from the market telling individuals how valuable their labor, land, and capital are. Entrepreneurs cannot simply decide wages for themselves; they are beholden to the subjective valuations of consumers. If an entrepreneur decides to pay too much for wages, he will lose his profitability and be replaced by entrepreneurs who pay a more appropriate price. If the entrepreneur decides to pay a lower wage, he will lose his workers to others willing to pay a higher price. In order to remain an entrepreneur in a particular line of business, the entrepreneur has no choice but to pay workers for their marginal productivity. Under a free-market system, capitalists and entrepreneurs cannot oppress workers, because the workers have the freedom to leave and work elsewhere and because the consumers have the freedom to buy their products elsewhere. Only by carefully and correctly walking the tightrope between workers and consumers can entrepreneurs continue to operate.

Economizing in the Market Order

We can think of the market system as the larger framework in which all the previously discussed acts of economizing can be practiced with the greatest increase in productivity. Labor, capital, technology, power, trade, and money are all tools that can be employed far more productively in the context of free and impersonal exchange on the market. As a result, the market economy has steadily increased the real wages of workers, because the market economy is constantly finding new ways of increasing the value of human time, by using it most productively to satisfy the needs of other humans.

Market participants communicate their changing preferences and conditions to each other through their actions in buying or not buying at particular prices. This process of mutual cooperation allows all market participants to act in their own best interest, while coordinating their actions to better benefit one another. All preferences of consumers are expressed to other market participants in terms of their choices to buy or not buy at a particular price, giving producers valuable knowledge on which to base their production decisions. As Mises put it:

The market process is the adjustment of the individual actions of the various members of the market society to the requirements of mutual cooperation. The market prices tell the producers what to produce, how to produce, and in what quantity. The market is the focal point to which the activities of the individuals converge.

Mises further adds:

In nature there prevail irreconcilable conflicts of interests. The means of subsistence are scarce. Proliferation tends to outrun subsistence. Only the fittest plants and animals survive. The antagonism between an animal starving to death and another that snatches the food away from it is implacable. Social cooperation under the division of labor removes such antagonisms. It substitutes partnership and mutuality for hostility. The members of society are united in a common venture.

Consumer Sovereignty

The careful analysis of the market process illustrates why in a free market, the consumer is king. Individuals are sovereign in a market economy in their capacity as consumers, because the producers have no way of forcing them to purchase their goods, except by producing goods that meet the needs and desires of the consumer at a price they can afford. Producers invest their capital resources in the production process and are reliant on consumers liking their product for their investment to not go to waste. Producers are in no position to dictate terms or exploit consumers, who have full choice. As Mises explains:

If they were not intent upon buying in the cheapest market and arranging their processing of the factors of production so as to fill the demands of the consumers in the best and cheapest way, they would be forced to go out of business. More efficient men who succeeded better in buying and processing the factors of production would supplant them. The consumer is in a position to give free rein to his caprices and fancies. The entrepreneurs, capitalists, and farmers have their hands tied; they are bound to comply in their operations with the orders of the buying public. Every deviation from the lines prescribed by the demand of the consumers debits their account. The slightest deviation, whether willfully brought about or caused by error, bad judgment, or inefficiency, restricts their profits or makes them disappear. A more serious deviation results in losses and thus impairs or entirely absorbs their wealth. Capitalists, entrepreneurs, and landowners can only preserve and increase their wealth by filling best the orders of the consumers.

Mises further compares the power of consumers in the market to the democratic process, showing how it is superior, because it caters to the needs of all, whereas democracy only caters to the need of the winning majority:

With every penny spent the consumers determine the direction of all production processes and the details of the organization of all business activities. This state of affairs has been described by calling the market a democracy in which every penny gives a right to cast a ballot. It would be more correct to say that a democratic constitution is a scheme to assign to the citizens in the conduct of government the same supremacy the market economy gives them in their capacity as consumers. However, the comparison is imperfect. In the political democracy, only the votes cast for the majority candidate or the majority plan are effective in shaping the course of affairs. The votes polled by the minority do not directly influence policies. But on the market no vote is cast in vain. Every penny spent has the power to work upon the production processes. The publishers cater not only to the majority by publishing detective stories, but also to the minority reading lyrical poetry and philosophical tracts. The bakeries bake bread not only for healthy people, but also for the sick on special diets. The decision of a consumer is carried into effect with the full momentum he gives it through his readiness to spend a definite amount of money.

A Contrast of Approaches

For as long as governments have existed, the urge to set prices by decree has existed and has resulted in a slew of terrible and predictable consequences. But the many and various futile attempts by central governments to fix prices have had one positive consequence: They have made a lot of people understand economics as a product of human action, even though they may not quite articulate it in these Misesean terms. By contrasting the analysis of the politician imposing the price control and the economist, we can clearly see the power of the economic way of thinking.

The politician who is unhappy about a market price and seeks to alter it is thinking of the price as something arbitrary, which he can set. He is not thinking in the economic way because he does not view prices as the result of human action, reflecting human choice. He ignores the element of individual and personal choice that goes into determining prices and instead focuses on the political and social implications of these prices. He compares the current reality to a hypothetical reality in which the price is lower and the quantity consumed is higher, while everything else remains the same.

Most political leaders do not get to their positions through the strength of their understanding of economics. Arguably, understanding economics is a significant hindrance to success in politics. Politicians consider the prices of economic goods and services purely as a measure of their affordability, and they know that the lower the prices, the happier the population. Without understanding prices as the emergent outcome of human action in response to economic reality, the politician thinks he can manage prices to achieve his desired outcomes, and so he will pass laws that mandate maximum prices for specific goods. The faulty reasoning assumes that if the price of a good is set by law, then buyers and sellers will have no choice but to buy and sell at that price.

Should the political leader seek to consult an economist, he is likely to prefer the advice of quantitative economists who can produce seemingly valid rationales for these policies. A quantitative economist can mathematically model the effect of prices on economic activity and find a theoretical quantitative relationship between the price of a good, the level of spending in the economy, and economic growth. It is possible to hypothesize a causal mechanism, based on real-world data, in which lowering the price of an essential good causes an increase in the living standard of a large section of the population, resulting in more savings and investment and faster economic growth. With the quantitative observation of the magnitudes and untestable assumptions about the flow of causality, the quantitative economist can provide the government with a seemingly scientific formula for improving the state of the economy by mandating critical prices by law. Without a constant unit of measurement, these equations cannot be accurate, so any result desired can be arranged.

From the perspective of the sound economist, however, price is more than just a measure of the affordability of a good. It is a product of voluntary human action and choice and the solution to a calculation problem for the producer and consumer. Should the government impose a different price for the good, there is no guarantee that the individuals involved would perform the same actions they had performed otherwise, nor that they can satisfy each other in the same way.

Prices are not arbitrary numbers placed by merchants, they are arrived at through a complex interplay of humans acting and affecting market supply and demand. A market transaction taking place at a particular price indicates that both the buyer and seller chose to accept this price. Both of them would obviously prefer other prices; the buyer would have preferred a lower price, and the seller would have preferred a higher price, but the actual price was clearly acceptable for both, since they traded. If a politician were to intervene and force the price to change by law, there is no reason to assume the buyer and seller would make the same decisions as before. And from the perspective of an economist, such a law would be far more destructive than whatever prices had emerged on the market, no matter how distasteful they were to the leaders.

What a market price for a good tells us is that the seller is happy to sell this good at this price, and the buyer is buying it. Should buyers refuse to buy this good at that price, then the producer would have to drop his prices. Should he be unable to drop his price to meet the consumers’ valuation, then the good does not get produced. In order for the business to sell any particular good, the price needs to compensate the producer for the entire cost and opportunity costs incurred to make the product available. When price controls set a maximum price for a good that is below the cost of the producer, then the producer will simply stop selling it, leading to shortages.

Producers, being self-interested humans, will not sell a good for a price that does not cover their entire cost of production. They would rather go out of business and stay home than work in a business that loses them money. So trying to mandate lower prices simply results in the destruction of the human incentive to produce a good, resulting in higher prices and even lower supplies. The other inevitable consequence of price controls is the emergence of black markets where the seller and buyer can transact at rates suitable to both of them, but without the attention of the government.