Table of Contents

The services money renders are conditioned by the height of its purchasing power. Nobody wants to have in his cash holding a definite number of pieces of money or a definite weight of money; he wants to keep a cash holding of a definite amount of purchasing power. As the operation of the market tends to determine the final state of money’s purchasing power at a height at which the supply of and the demand for money coincide, there can never be an excess or a deficiency of money.

– Ludwig von Mises

The Problem Money Solves

People who benefit from trade have an incentive to pursue more trade. But the main impediment to the expansion of trade between people is the problem of lack of coincidence of wants. When humans try to find solutions to this problem, their actions naturally lead to the emergence of money, which is defined as a general medium of exchange. By understanding how the problem of coincidence of wants is solved using money, we can discern the properties that matter for money to operate successfully, and as a result, understand the properties that make for good money that emerges freely on the market.

In large families or small tribes, trade is likely to be straightforward and direct. This is because everyone knows everyone else, the degree of specialization in production is very low, and there are a small number of goods and services available. In such a primitive setting, there is not much need for the emergence of money. With only a few goods available, individuals can trade these goods with one another directly. The hunter can just exchange his extra rabbits for fish from the fisherman, at whatever exchange rate the two find agreeable, in a transaction called barter. Because strong bonds exist between the people in a small group, individuals do not even need to provide present goods for immediate exchange; it is possible to exchange a present good for a promise of a good in the future. The hunter can give a farmer rabbits today in exchange for some of the farmer’s grain crop in harvest season in a few months. Receiving a good today and promising repayment in the future is a transaction called debt.

Barter and debt are two ways of conducting trade, but they are only practical in specific, and increasingly rare, circumstances. Barter happens on the rare occasion in which a person wants to exchange a good for another good whose owner wants the first good. This is what is referred to as the coincidence of wants: Both parties to a transaction want exactly what the other party has to offer. The fisherman needs to find a hunter who is looking for fish, and the hunter needs to find a fisherman looking for rabbits. If rabbits and fish are the only goods in this economy, they are far more likely to find each other than if there were millions of other goods and services, as is the case in a modern economy. The more people in a society, and the larger the number of possible goods and products, the less likely it is for these two people to find one another for the trade to take place. In an economy in which there are only 100 people and 10 goods in total, everyone will be employed in the production of one of these goods, and everyone will need to obtain a supply of these goods. The odds of finding a trading partner whose wants coincide with yours decline drastically as the number of people in an economy, and the number of goods and services available, increases.

In the modern world, where a large variety of goods and services exist, barter is practically nonexistent. Siblings and friends might, by virtue of their proximity, identify occasions for direct exchange and engage in it. But nobody in their right mind wakes up thinking of how to find a way to exchange goods and services for one another directly. The search costs would likely exceed the gains from the exchange. No group larger than a small tribe with very few goods can ever have an economy built on barter.

The same analysis applies to the use of debt as a medium of exchange. In a small society where individuals have strong bonds and depend on repeated interaction with one another for survival, it is possible to use debt to facilitate trade. But as the size of society increases, and as interactions begin to take place between strangers who are highly unlikely to have repeated interactions with one another, the use of debt becomes unworkable. As an economy grows, trusting a trade partner becomes a more risky proposition. There is no good reason for someone to accept a promise of payment from a stranger they may never see again, as there is no good reason to believe that a stranger cares about his reputation with someone he might not meet again.

As more individuals enter an economy and the number of goods multiplies, the coincidence-of-wants problem becomes more pronounced. Human reason can find a solution to the problem by engaging in indirect exchange: Selling goods for a good whose only purpose is to be exchanged for the desired good. In indirect exchange, an individual will acquire a good not because she wants it, but because she wants to exchange it for something she actually wants. When the fisherman discovers that a hunter with a rabbit he wants is not interested in fish but is looking for grain, the fisherman can exchange his fish for grain and give the grain to the hunter in exchange for rabbits. Grain, to the fisherman, is not a consumer good, it is a medium of exchange: It is a good acquired not for the sake of its own utility, but for the sake of exchanging it for the good the holder actually desires.

Man’s ability to reason makes it inevitable that these indirect exchange transactions would emerge to solve the problem of coincidence of wants. Man’s actions, however, have consequences that extend beyond the aims of direct reason. As the scope of markets expands and humans increasingly resort to indirect exchange, it is only natural that some goods will perform that function better than others, with important consequences to the parties involved. “Salability” is the term Carl Menger gave to the property that makes a money desirable, and the more salable a good is, the more successful it is as a money. Understanding the function of medium of exchange allows us to understand the properties that make a specific type of money desirable.

Salability

Menger defines salability as the ease with which a good can be sold in a market at any convenient time at current prevalent prices. The more salable a good, the more likely the owner is to obtain a prevalent and undiscounted market price in exchange for his good when he chooses to sell it. A good with low salability is a good whose owner would expect to offer a significant discount on the price of the good if he wanted to sell it quickly. A highly salable good is one with significant market depth and liquidity, making it possible for the holder to obtain the prevailing market price whenever they want to sell it.

A great example of a highly salable good today is the one-hundred-dollar bill, accepted worldwide by merchants and currency exchange shops more frequently than any other physical monetary medium. A holder of a hundred-dollar bill who is looking to exchange it for goods and services will rarely ever need to sell it for something else to provide to a seller he is conducting a transaction with, nor will anyone with a hundred-dollar bill ever need to sell it at a discount. The holder will usually find someone to take it off their hands quickly and at face value. By contrast, a good with low salability is one for which demand on the market is intermittent and varied, making it difficult to sell the good quickly and requiring its owner to offer a discount in order to do it quickly. A great example of this is a house, car, or other forms of durable consumer goods. Selling a house is much harder than selling a one-hundred-dollar bill because it involves viewings and significant transaction costs, as well as waiting for the right buyer who values the house at the seller’s asking price. The seller might need to offer a significant discount to sell the house quickly. In capital markets, the most salable instruments are U.S. Treasury bonds, which at the time of writing are collectively worth around $28 trillion. Most large and institutional investors use U.S. government bonds as their store of value and treasury reserve asset because it is easy to liquidate large quantities without causing large movements in the market.

Central to Menger’s analysis of salability is the measure of the spread between the bid and ask prices for assets. The bid is the maximum price a buyer is willing to pay, and the ask is the minimum price a seller is willing to take. Bringing large quantities of a good to market would cause the spread between the bid and ask prices to widen because, as the marginal utility of the good declines with increased quantities, potential buyers begin to offer lower prices. The more a good’s marginal utility declines with rising quantities, the less suited it is to the role of money. The smaller the decline in a good’s marginal utility, the less the bid-ask spread will widen as larger quantities are brought to the market, the more salable the good is, and the more suitable it is for use as money.

We can also understand this process from the perspective of traders and merchants buying goods to sell later. For them, growing stockpiles of a good reduce the chance of each marginal good being sold and increase the risk of price declines hurting the seller. Thus, they will bid at lower levels for increasing quantities of a good. The faster the spread between the bid and ask grows, the less salable the good. Goods for which the spread rises slowly are more salable goods, and these goods are more likely to be hoarded by anyone looking to transfer wealth across space or time. In other words, the most salable goods will fluctuate the least in relation to the quantity brought to a given market.

Many factors, discussed below, can affect the salability of goods, resulting in a wide variety of degrees of salability. The goods with the highest salability are the ones whose marginal utility declines the least with increasing stockpiles, since increasing stockpiles can be easily exchanged for other goods. Menger defines money as the most salable good. During the natural course of market transactions, some goods will emerge to have a lower diminishing marginal utility and a higher salability than other goods, encouraging people to hold them more, which leads to increased liquidity of the good and further increases in salability. This process will naturally amplify the salability of the most salable goods, thereby concentrating the monetary role in the most salable goods. Eventually, this monetary role will concentrate in one good alone, the most salable good, the generalized medium of exchange: money, the goodwhose marginal utility declines the least.

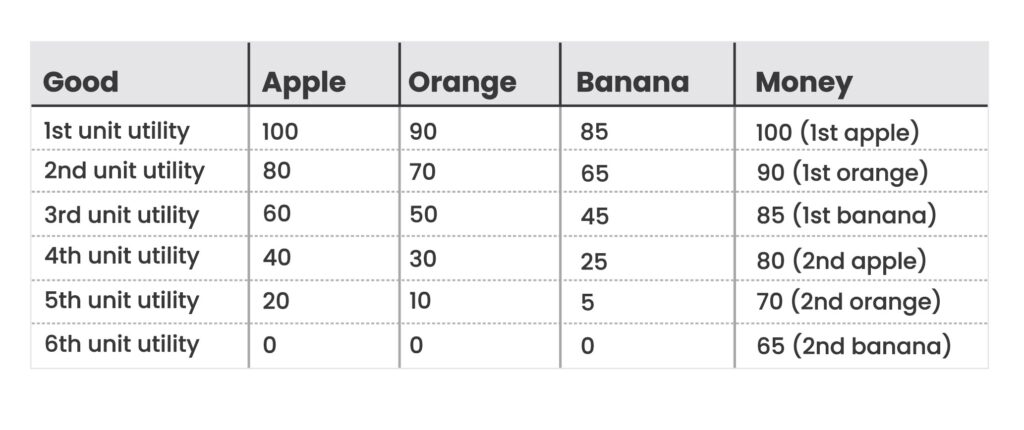

The numerical example below can help us understand the salability of money. For simplicity, it is assumed that the market price of each apple, orange, and banana is the same as one monetary unit, and the utility is expressed in cardinal terms, though it should be well understood that humans only understand utility in ordinal terms, as discussed above.

As the marginal utility of each good declines, the marginal utility of the monetary units declines less than the utility of the good declines. Being the most salable good, money is the easiest good to exchange for consumer goods, and this makes it a more desirable option for accepting payment. For this individual, accepting money as payment is a superior option to accepting apples, oranges, or bananas, because the money is easily exchangeable for whichever of these consumer goods the individual will value the most at any future point in time. Some economic goods are more suitable than others to fulfill the role of medium of exchange. The more suitable a good is to use for exchange, the more marketable or salable it is.

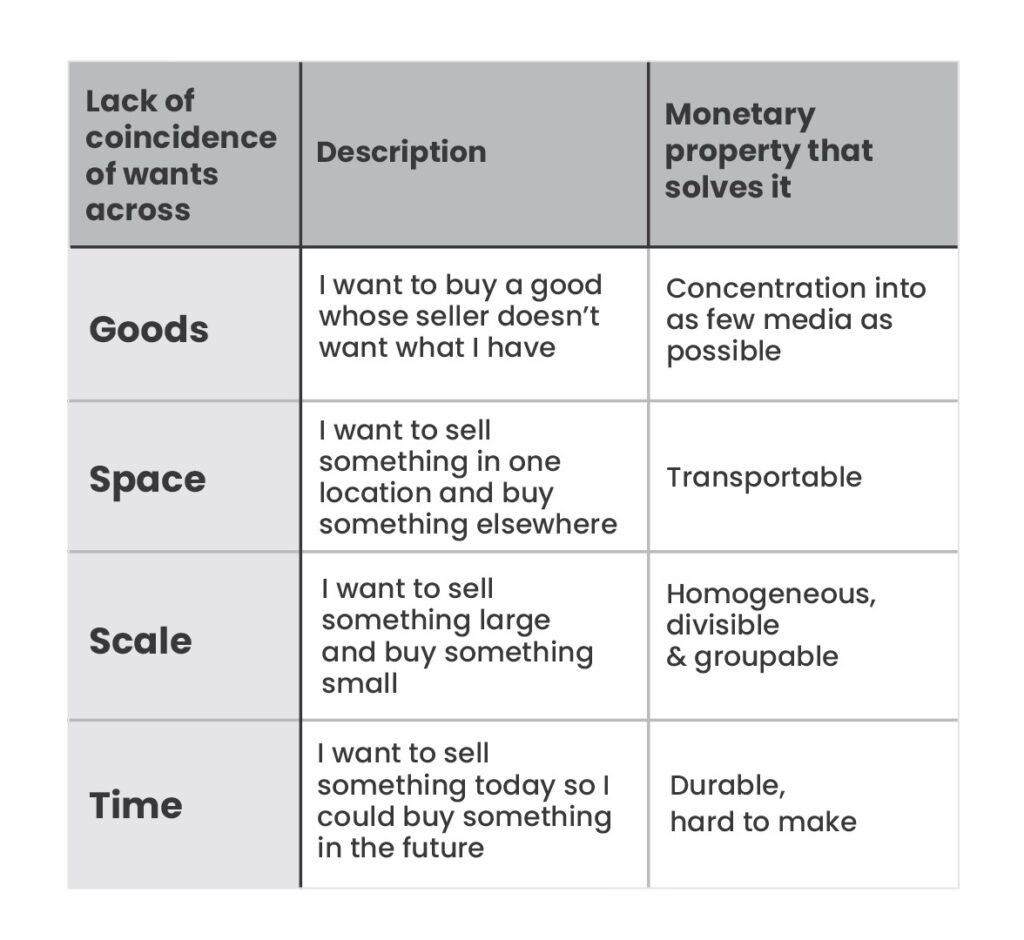

Understanding the problem money solves can help us identify the properties that characterize a good solution—in other words, they help us identify what makes something a good money. The lack of coincidence of wants is the problem money solves, and it manifests across several dimensions. There is the lack of coincidence of wants in the goods themselves, as discussed in the fish, rabbits, and grains example above. Beyond that, there is the lack of coincidence of wants across space. That is, a person might want to sell something in one location and obtain a good in exchange for it in another location. Trading your apples for a car would be hard enough in most scenarios, but it would still be harder if you needed to lug your apples 1,000 miles in order to conduct the transaction.

The third dimension to the coincidence of wants is the lack of a coincidence of wants across scales. When individuals want to directly exchange goods of different sizes and values, a partial exchange is not always possible. The person who wants to sell apples cannot exchange each apple for a small part of a car from someone and then assemble the parts into one car. It would be impractical and inefficient to engage in trade with such different goods. Reason suggests some other, more divisible medium of exchange will solve the problem.

In addition to the dimensions of the good, space, and scale, there is a fourth dimension to the coincidence of wants: The lack of coincidence of time frames for trading, since a person might either want to sell an object today or over a period of time in order to obtain another good in the future. A person might want to sell apples over a three-year period in order to buy a car. It is not possible to accumulate three years’ worth of apples to exchange for a car, as the apples will spoil. Man’s reason naturally leads him to see the convenience of exchanging apples to accumulate a medium of exchange—one that will not rot or be eaten by worms—with which to purchase a car in the future.

By examining the different axes along which the problem of coincidence of wants emerges, it becomes possible to identify the properties that make for a good monetary medium. The characteristics that make something a good medium of exchange are what make it a good solution to the coincidence-ofwants problem in its four dimensions. As Murray Rothbard put it: “Tending to increase the marketability of a commodity are its demand for use by more people, its divisibility into small units without loss of value, its durability, and its transportability over large distances.”

The third facet of the problem of coincidence of wants helps us understand why metals were naturally a superior choice of monetary medium to artifacts and other consumer goods. Because metals are made up of a homogenous substance, large quantities of metal can be divided into smaller denominations, while small quantities can be combined into larger pieces without significant loss of economic value or a change in the metal’s physical properties. Metal, then, is highly divisible and groupable. This is not a property of artifact monies like seashells, cattle, and glass beads.

The second facet of the problem of coincidence of wants, salability across space, helps us understand the ancient suitability of casting gold and silver in a monetary role, and the modern limitations that prevent these metals from playing this role today. Being inert, silver and gold do not rot, ruin, rust, or disintegrate. These metals can be transported relatively easily, with little fear that transportation will alter their properties or compromise their integrity. As they can condense large amounts of economic value into small weights, these metals were particularly economical to move around compared with other monetary media. But as modern telecommunication and transportation industries grew more sophisticated with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, the world became far more interconnected, and the scope of global trade began to expand across space. With increasingly global and long-distance trade, the movement of physical gold and silver was no longer an economical method of conducting trade. Credit based on these metals emerged as a medium of exchange in its own right, and eventually, government capture of banking institutions allowed government credit to effectively displace gold and silver in World War I, as discussed in more detail in The Fiat Standard.

Historically, silver and gold had a dual monetary role as they complemented each other in terms of salability across scales. Gold, being more valuable, was difficult to divide into very small pieces for transactions of small value, while silver, being less valuable, was not very suitable for large transactions. Historically, copper also served as a monetary medium used for smaller units of value than silver. Over time, copper and silver lost their monetary roles for reasons pertaining to salability across time, as discussed below. With the globalization of markets and an unprecedented degree of international trade at the end of the nineteenth century, the global economy settled on one money, gold, as the solution to the problem of coincidence of wants.

Salability across Time

The fourth facet of the coincidence-of-wants problem pertains to the ability to exchange value across time. To preserve or exchange value over time requires a medium of exchange that can hold its value across time without much loss. The better a medium of exchange is at holding its value across time, the more suitable and desirable it is as a medium of exchange. This helps us understand why metals would have a monetary role, as they are generally durable, and why precious metals—like gold and silver in particular—would have a more prominent, long-lasting monetary role than base metals like iron and copper. Being inert and indestructible gave precious metals a significant advantage over metals that disintegrate over time. But the real advantage of these metals lies not merely in their durability, but in the effect of this durability on their supply dynamics. The major feature distinguishing precious metals from all other forms of money is the relative magnitude of their stockpiles to their annual production. As these metals do not corrode or ruin, their stockpiles continue to grow over time, and rarely ever become depleted. As technology advances and humans find more ingenious ways of increasing the supply of these metals, the stockpiles continue to grow, and existing production continues to be a small fraction of total liquid stockpiles.

This property is known as hardness, meaning the difficulty of increasing the existing liquid stockpiles of a good. And we can quantify hardness using a simple metric, the stock-to-flow ratio, wherein stock refers to the total aboveground liquid stockpiles that can be used in a monetary role, while flow refers to new annual mining output. This metric is simply the inverse of the annual supply growth rate, and theoretical reasoning as well as historical evidence indicate that this metric matters enormously when determining monetary status. All metals that can corrode are constantly being consumed in industrial processes, which alter their chemical properties and eliminate them from stockpiles used to store value. For all these metals, existing liquid stockpiles are of the same order of magnitude as the annual production of the metal. There are very few stockpiles of copper, nickel, brass, and other metals for use as a liquid store of value. To the extent such stockpiles exist, they are held in reserve for producers who use large quantities of them and need them to hedge against potential supply problems stalling their production. The production of these metals is constantly being deployed for industrial use, so the stockpiles do not increase significantly. New production is thus significant compared to existing stockpiles, making the price of the metal highly vulnerable to supply shocks. Such metals are unsuited to playing a monetary role, since their salability across time can be compromised by supply shocks, and their employment as a monetary medium will necessarily bring about the supply shocks that destroy their monetary role.

To understand why, we must first distinguish between market demand for a good, where consumers demand the good in order to hold it or consume it for its own sake and properties, and monetary demand for a good, where consumers hold the good merely as a monetary medium, with the aim of exchanging it later for other goods and services. A person can choose any good as their store of value and medium of exchange and with that choice, she adds monetary demand on top of its market demand, resulting in an increase in its market price. This will naturally lead to an increase in the quantity of resources, capital, and labor dedicated to its production. This is where the stock-to-flow matters. If the good has a low stock-to-flow ratio, the portion of the liquid supply on the market that is produced by miners will be very high, and increases in mining output will correspond to large increases in liquid market supply, thus bringing the price down and punishing the savers. The market is highly responsive to miners’ increases in production because the daily liquidity on the market arises primarily from miners’ new production, and not from the stockpiles held by consumers, as consumers predominantly hold the good to deploy it in market production and not to resell it. The predominantly industrial nature of these metals means that anyone using them as money is simply donating their wealth to miners in a process we could describe as the easy-money trap. Storing value in a good with a low stock-to-flow ratio simply causes that value to be captured by the producers of the good.

In order for a commodity to resist the easy-money trap, and have good salability across time, its liquid stockpiles must be significantly larger than annual mining production, so when its monetary demand increases, increases in mining production will have little impact on market conditions, since mining output is only a small fraction of the liquid supply being traded. With a high stock-to-flow ratio, increases in monetary demand translate to increases in price, but when the stock-to-flow ratio is low, these increases translate to increased miner profits.

Hard money is money whose stockpiles are hard to increase significantly, no matter what its producers do, since the producers’ output is a tiny fraction of the existing stockpiles. Easy money is money whose liquid stockpiles are easy to increase. This term applies equally to commodity monies and to national currencies. Easy money is common vernacular across the world, particularly in countries cursed with bad monetary policies, where citizens understand full well the desirability of relatively hard national currencies like the dollar and the euro on the one hand, and the lack of desirability of their local currency, which is easy for the local government and central banking cartel to produce in increasing quantities.

The stock-to-flow metric has a value close to 1 for all metals, except gold and silver. As base metals’ production is constantly being consumed in industrial applications, existing liquid stockpiles are never significantly higher than annual production. Because these metals also rust and corrode in various ways, there is little incentive to store large quantities for the long term. The 3 main exchange warehouses for copper consistently hold less than 1,000,000 tons of copper between them, whereas annual copper production is around 25,000,000 tons. Even if global copper warehouses contained 20 times more copper than the 3 main ones, that would still not suffice to raise copper’s stockto-flow above 1. In September 2020, zinc stockpiles at the 3 main exchanges totaled 133,300 tons, while annual production was around 13,000,000 tons, around 100 times larger than the stockpile, giving zinc a stock-to-flow ratio of 0.01.

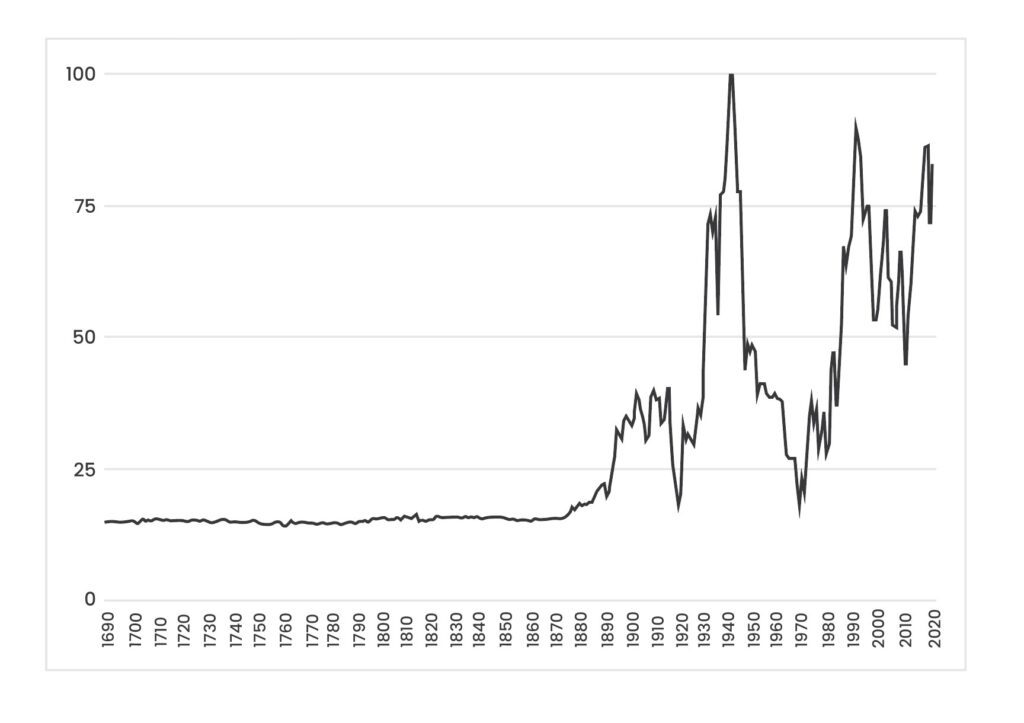

Because gold cannot be consumed or altered as a metal, it is mainly acquired to be held as a liquid monetary asset, so existing stockpiles are usually many orders of magnitude larger than annual production. Even as annual production increases with increased efficiency, stockpiles also continue to increase, ensuring that the stock-to-flow ratio remains significantly higher than 1. Examining the data over the last century shows that gold’s stock-to-flow ratio has remained consistently around 60, translating to an annual supply growth rate of around 1.5%. Even as annual production of gold continues to increase over time, stockpiles also increase, and the ratio remains roughly constant, as can be seen in Figure 6.

Silver is similar to gold in having a stock-to-flow ratio higher than 1, but historically, its stock-to-flow ratio has declined as increasing quantities of silver used in industrial applications are effectively taken out of the liquid stockpiles. If one were to measure the silver stock-to-flow ratio based on the total stock of above-ground silver, then its stock-to-flow ratio is between 30 and 60. But the silver deployed in industrial applications cannot be counted as part of the liquid stockpile since it cannot play a monetary role, nor can it be used to settle trade and debt. The price of electronics, machinery, cutlery, or jewelry that contains silver is not a function of the monetary price of the silver it contains, which usually represents a tiny fraction of the total price, but of the consumer valuation of the good itself—as a consumer or capital good, not as a monetary good. Trying to extract the silver from these goods to convert it into a monetary asset, in the shape of bars or coins, is a costly process no different from extracting silver from the crust of Earth. When the measure of stockpiles used refers only to monetary stockpiles, in the form of silver bars, coins, and investment products, then the stock-to-flow ratio is closer to 4. This is still significantly higher than nonmonetary metals whose stock-to-flow ratio is a fraction of 1, but nowhere near high enough to hold on to value well enough to maintain a monetary role. That is why, as silver’s market value has declined relative to gold over the past century and a half, its nonmonetary uses have grown to consume the majority of its existing stockpiles.

If one were to consider all the silver deployed in industrial applications as part of the silver stockpile, then silver’s stock-to-flow ratio would be significantly higher. As nonmonetary uses of silver have grown, they have effectively consumed the stockpile of monetary silver and brought silver’s stock-to-flow ratio down. Concomitantly, silver’s market value has declined in real terms.

Silver’s demonetization arguably has its roots in the metal’s lower stock-toflow ratio and the advancement of modern banking. As modern banking and telecommunication technology advanced in the nineteenth century, people could transact with financial instruments such as paper money, checks, and letters of credit backed by gold held by banks and central banks. This made gold transactions possible at any scale, thus obviating silver’s monetary role, which was primarily geared to small transactions, and allowing everyone to hold the assets with the highest stock-to-flow and the greatest likelihood of appreciating.

Silver’s demonetization took off in earnest in 1871, after the end of the Franco-Prussian war. Germany, which was then the largest economy still on a silver standard, asked for its indemnity from France in gold and used the indemnity to switch to a gold standard. As Germany’s demand for silver declined and its demand for gold rose, the value of silver began to decline from its ratio to gold of around 15:1, causing economic losses for silver holders and countries on a silver standard, encouraging them to drop their silver in exchange for gold. Since then, the ratio of gold price to silver price has just been rising; it is currently around 80, or more than 5 times its ratio 150 years ago. Countries that were late to abandon the silver standard, such as India and China, experienced severe economic hardships from the decline in the value of their currency.

The high stock-to-flow ratio of gold destined it to play a monetary role, because it gives it the best salability across time. As the production of gold adds only small increments to the stockpile of the metal, it makes it hold its value better over time, causing a growth in the market value stored in it over time, through its appreciation against other commodities. This increase in the value of balances held in a medium corresponds to an increase in the liquidity of the market, a decline in the bid-ask spread, and therefore an increase in the marketability of the commodity. This trend is only amplified as people become more aware of it, allocating their cash balances to the good with the best expectation of future value and the smallest bid-ask spread.

The framework of salability across time and stock-to-flow ratio are particularly interesting tools to use to analyze the rise of bitcoin, a new monetary phenomenon with a pre-programmed supply schedule and a stock-to-flow ratio that constantly increases until it reaches infinity. This analytical framework forms the foundation of my first book, The Bitcoin Standard.

Why One Money?

Increased monetary demand for the most salable commodity will further increase its price and value, thus enhancing its salability across time even further and amplifying the size of its liquidity. As wealth will naturally concentrate in the most salable commodities, this further amplifies their salability. Holders of the most salable commodity will have a larger market and a larger amount of liquidity with which to trade. Increasing use as money further enhances a good’s value as money, thus amplifying the incentive to use it as money, resulting in a winner-take-all dynamic in the market for money. The historical record shows this to be the case. The entire planet had converged on gold as money by the end of the nineteenth century, even as many thousands of different goods had been used for this role across the planet. The survival of silver’s monetary role into the nineteenth century was a result of its superior salability at small scales, but as modern banking obviated this, gold became the world’s money. Something similar is happening in the modern global market for government monies, where there appears to be an insatiable demand for the most marketable government money, the U.S. dollar. Not only are large numbers of non-Americans seeking to hold the U.S. dollar as opposed to their national currency, virtually all national currencies are backed by dollars, as their central banks hold large quantities of dollars they use for international trade.

The more common the medium of exchange, the more salable it is and the larger the potential market its holder can sell to. Individuals will naturally gravitate toward the most salable goods, and that in turn will amplify their salability, attracting more individuals to use them. Rothbard explained the process as follows: “As the more marketable commodities in any society begin to be picked by individuals as media of exchange, their choices will quickly focus on the few most marketable commodities available.”

The fundamental problem of coincidence of wants involves the coincidence of desires for goods. As the size of an economy grows, so does the degree of specialization and the number of goods that can be produced, thus complicating the possibilities for direct exchange. The only possible solution to this problem, and the only way a market’s extent can grow, is to employ indirect exchange, wherein people acquire goods purely for the purpose of later exchanging them for other goods. As humans indirectly exchange various goods, it is only natural that some goods will play the role of medium of exchange better than others, rewarding those who employ them and punishing those who employ media of exchange that are unsuited for this role. As time goes by, the benefits of employing the suitable media of exchange become more pronounced, as do the harms from employing bad media of exchange. People who adopt nondurable, non-homogenous, non-divisible, and non-transportable goods will witness their wealth decline over time, while those who adopt durable, homogenous, highly divisible, transportable goods will witness it increase. As time goes by, primitive and unsuitable monetary media are discarded and ignored as their users lose their wealth, and in the long run, the most important metric in determining monetary status becomes the metric of hardness, or stock-to-flow ratio.

The process of monetary competition is driven both by human action and the brute physical, chemical, and geological realities governing the production of different goods. Intelligent individuals will use their reason to try to arrive at the best form of money to use, but even if no one were to think of this, economic reality would impose itself to produce a similar outcome. Those who use the best monies will accumulate more wealth, whereas those who use unsuitable monies will lose their wealth, and over time, the majority of wealth will end up concentrated with those who use suitable monies, whether they consciously desired this outcome or not.

The above analysis explains the emergence of money through its suitability to perform the quintessential function of money: To act as a medium of exchange. Rothbard defined money as a commodity that comes into general use as a medium of exchange. While the concept of a medium of exchange is a precise one, the concept of a “general medium of exchange” is not. It is easy to identify something that is functioning as a medium of exchange, but identifying it as a general medium of exchange is a matter of subjective judgment.

Money and the State

The Austrian approach to economics as the study of human action can help us understand and identify the goods likely to earn a monetary role just by analyzing the way humans act to solve the problems of exchange. Even before humans could record their actions, they engaged in direct and indirect exchange. And as humans seek to satisfy their desires through indirect exchange, some goods begin to play that role better than others, and those who employ these media of exchange benefit from using them. Others copy them, and the successful solutions become more widespread. If they do not copy the successful solutions, they lose wealth to those who do. The better solutions impose themselves as economic reality always does, by rewarding those who adopt them and punishing those who do not. There is no need for a central authority to decree a medium of exchange and compel everyone to accept it. Money emerges from the market, out of the actions of humans, and not as a result of any central-planning government.

As Carl Menger explained: “Money is not an invention of the state. It is not the product of a legislative act. Even the sanction of political authority is not necessary for its existence. Certain commodities came to be money quite naturally, as the result of economic relationships that were independent of the power of the state.” Certain goods will naturally succeed at playing the role of money better than others, and the market process will bring these to the fore and cause their adoption as money to grow. The process is no different from the selection of particular commodities for the production of a consumer good: Like leather is used for shoes, gasoline for car propulsion, and silicon for electronics, the market process results in the selection of the most salable goods as money.

Mises went further than Menger in explaining how the choice of money can emerge purely on the market through his regression theorem, which explained how a normal market good can develop into a monetary good when it acquires monetary demand, thus raising its value and increasing its salability. As the good acquires increasing monetary demand, its price increases beyond its market demand price.

The process of monetary emergence and selection by the market can be understood entirely with reference to human action. There is no need to invoke any coercive authority to select or manufacture a monetary medium. Money, like all goods, emerges on the market because it offers a utility that makes individuals give value to it. The historical and empirical record supports this contention, as it clearly shows that monetary media predate government monetary mandates. Gold’s global monetary role was not conferred by some government authority. It won its monetary role on the market, and government authorities had to accept gold as money on the market if they wanted to operate successfully. Gold did not become money because it was minted into government coins. Government coins became money because they were minted from gold.

History shows no single example of a good or asset gaining its monetary role through government mandate. Modern government money is referred to as fiat money, based on the Latin word fiat, which denotes the decree of authority. Yet, it did not become money by fiat. All existing government monies originally acquired their monetary role through the free market’s choice for money, gold. Only by hitching their monetary wagons to the market’s choice could government “fiat” be accepted as money in the first place, and only by fraudulently revoking their money’s redemption for gold did “fiat” money come into existence, not by pure fiat. The eventual severing of gold redemption does not alter the fact that no money ever gained its monetary role by fiat. Further, the continued need for governments to impose monopolies on banking and legal tender laws illustrates that their imposition of money cannot survive free-market competition. Governments could not decree monetary value away from gold; they confiscated it by force and accumulated it. And still, more than a century after the end of the gold standard, the world’s central banks continue to stockpile ever-increasing quantities of gold.

Another powerful refutation of the statist theories of money comes from the emergence of bitcoin, which in the last 14 years has grown from nothing to become one of the world’s 20 largest currencies, all without a single legal authority promoting or decreeing its use. El Salvador announced bitcoin as legal tender in 2021, but that came after bitcoin had already grown to become one of the world’s 10 largest currencies in total valuation. As with gold, silver, and all forms of money, statist recognition follows economic reality; it does not predate or dictate it. Had money been an invention of the state, and had it needed state sanction to operate, bitcoin could not have functioned as successfully as it has.

Value of Money

Like the previous methods of economizing, money is a tool humans use to increase the quantity and value of the time they have on Earth. The introduction of money to an economy will reinforce all three drivers of economic growth and progress. We can understand the economic significance of money with reference to the three main functions it performs: Medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

1- Increase the division of labor

As money eliminates the problem of coincidence of wants, it allows for a larger scope of trade between strangers who do not need to trust each other or be part of political and economic structures that protect them. The establishment of a money on the market increases the scope for specialization and division of labor, immensely widening the market for every consumer and every product. The more effective a monetary medium is at holding its value across space, and the more commonly it is held by others, the more potential trading opportunities it offers to its holder and the larger the extent of the market. As individuals realize they can meet an increasing number of their needs by exchanging goods with others, they are more likely to seek cooperation and peace with strangers they will never interact with twice. With money, human labor, capital accumulation, technological innovations, and trade take place in a large extended system of impersonal exchange. People who do not know each other, and who do not coordinate with one another directly, nonetheless manage to collaborate to produce highly sophisticated products over complex production structures. Money is an essential tool for human civilization, and its destruction has always coincided with the destruction of society and civilized living.

2- Allow for economic calculation

An important implication of the use of money is that all prices are expressed in terms of one good. In an economy with money, money is one half of every transaction. A barter economy with 10 goods would require 45 different prices, each expressing one good in terms of another (number of individual prices = n(n-1)/2, where n=number of goods). In contrast, a money economy with 10 goods (including the monetary good) would require only 9 prices (number of individual prices = n-1). The number of prices in a barter economy increases exponentially with the number of goods whereas the relationship between the number of prices and goods in a money economy is linear. We can see that a barter economy with 100 goods would require 4,450 different prices whereas a money economy with 100 goods would only require 99 prices. A barter economy with 1,000,000 goods would require 500 billion different prices but a money economy with 1,000,000 goods would require only 999,999 prices. The introduction of money to an economy thereby drastically reduces the number of prices required for exchange, bringing extraordinary efficiency to trade and markets.

Expressing the price of all goods in terms of the quantity of one good allows individuals to perform the enormously important process of economic calculation, which will be the focus of Chapter 12. With all prices in one unit, the entrepreneur is able to carefully calculate the costs and revenues expected from an undertaking. With calculation around the common denominator that is money, individuals can “construct an ever-expanding edifice of remote stages of production to arrive at desired goods because money allows for sophisticated calculation,” as Rothbard put it.

The degree of specialization that exists in the modern global economy is only possible with the use of money. Individuals are able to produce goods with absolutely no regard for their own consumption of the goods, knowing they can exchange them on the market for the most salable good, which they can then exchange for whatever goods they want. Complex processes of production and long supply chains are only possible thanks to the specialization allowed by money.

3- Lower time preference

Money, as a medium of exchanging value, allows its holders to preserve and transfer value to the future more efficiently than they would otherwise. Money, as explained above, will have higher salability than other market goods and will naturally end up being a good with high salability across time; it will therefore hold value better than most other market goods. As its salability allows for increasing provision for the future, the uncertainty of the future decreases, and individuals’ discounting of the future decreases. The decline in the discounting of the future is simply the lowering of time preference discussed in chapters 3 and 13.

Money can thus be understood as an important technology for the lowering of human time preference, as it is an extremely powerful tool for providing for the future, reducing the uncertainty around it, and allowing its holder to plan for it. Hedging against uncertainty is one of the main functions of money, and it is the reason that people prefer to hold some money rather than just holding capital goods, even though the latter produce a yield whereas the former does not. Investments are less salable and involve entrepreneurial risk. Money, at least in a free market, is the good with the most salability and least risk; it is the good that can always be converted to other goods with the smallest loss of its economic value. Money may not have a yield, but it is still held because it has the least uncertainty of all assets. Time preference is a measure of the discounting of the future, and uncertainty is a major contributor to the discounting of the future. Access to money, and in particular good and hard money, is a way to mitigate this uncertainty.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe said that the lowering of time preference initiates the process of civilization. Money plays a central role in that, and the harder the money is, the better it is at holding its value into the future and the less uncertain the future will be. And the more humans can plan for their future and thrive in the long run, the more money will cause time preference to decline and civilization to thrive.

Money’s Uniqueness

Money as a good is distinct from other goods in several ways. The first distinction is that money is neither a consumption good nor a capital good. Consumption goods are acquired to be consumed because they serve to satisfy human needs. Capital goods, on the other hand, do not satisfy human needs directly, but they are acquired because they can be used to produce goods that satisfy human needs. Money, however, is neither of these things. It is not acquired because it satisfies human needs, nor can it be used for the production of other goods; it is acquired purely to be exchanged in the future for other goods, be they consumption or capital goods.

Use as a medium of exchange is the quintessential function of money, and this means it requires no direct utility for humans to value it. The utility of money is derived from the utility of the goods it can be exchanged for. Money, like all goods, will have a diminishing marginal utility, but its marginal utility declines less than the marginal utility of all other goods, since each successive unit of money can be used to buy a unit from the next most valuable unit of any good and not just the next most valuable unit of the same good. For example, in an economy with money and only three goods, bananas, apples, and oranges, the utility of money will decline less than the utility of apples, oranges, and bananas each declines. Being liquid and easily exchangeable for other goods makes money a more useful thing to hold than other goods because it can easily be exchanged for whichever good the individual happens to value most at any time. This salability is the reason people prefer to be paid in money rather than in objects of limited salability. The high salability gives money the utility of whatever good happens to be most valuable to the holder of money at any time.

How Much Money Should There Be?

Perhaps the single most important monetary distinction between mainstream and Austrian economists is that Austrians think the absolute quantity of money is unimportant, and consequently, the money supply does not need to grow to satisfy the needs of a growing economy. Any supply of money is enough for any economy, as long as it is divisible. Money is unique from all economic goods in that it is the one good whose absolute quantity does not matter to its holder. Money does not offer any services to the holder except the ability to exchange it for other goods, making its own quantity irrelevant to the holder. The only aspect of money that matters to the holder is its purchasing power. The economic value of money lies in its ability to be exchanged for other goods, and so the value of money comes from its purchasing power, not from its quantity. Any supply of any money can be enough for any economy provided it can be divided up into small enough units.

As Rothbard explains:

[M]oney is fundamentally different from consumers’ and producers’ goods in at least one vital respect. Other things being equal, an increase in the supply of consumers’ goods benefits society since one or more consumers will be better off. The same is true of an increase in the supply of producers’ goods, which will be eventually transformed into an increased supply of consumers’ goods; for production itself is the process of transforming natural resources into new forms and locations desired by consumers for direct use. But money is very different: money is not used directly in consumption or production but is exchanged for such directly usable goods. Yet, once any commodity or object is established as a money, it performs the maximum exchange work of which it is capable. An increase in the supply of money causes no increase whatever in the exchange service of money; all that happens is that the purchasing power of each unit of money is diluted by the increased supply of units. Hence there is never a social need for increasing the supply of money, either because of an increased supply of goods or because of an increase in population. People can acquire an increased proportion of cash balances with a fixed supply of money by spending less and thereby increasing the purchasing power of their cash balances, thus raising their real cash balances overall.

Rothbard follows up by quoting Mises:

The services money renders are conditioned by the height of its purchasing power. Nobody wants to have in his cash holding a definite number of pieces of money or a definite weight of money; he wants to keep a cash holding of a definite amount of purchasing power. As the operation of the market tends to determine the final state of money’s purchasing power at a height at which the supply of and the demand for money coincide, there can never be an excess or a deficiency of money. Each individual and all individuals together always enjoy fully the advantages which they can derive from indirect exchange and the use of money, no matter whether the total quantity of money is great or small. Changes in money’s purchasing power generate changes in the disposition of wealth among the various members of society. From the point of view of people eager to be enriched by such changes, the supply of money may be called insufficient or excessive, and the appetite for such gains may result in policies designed to bring about cash-induced alterations in purchasing power. However, the services which money renders can be neither improved nor repaired by changing the supply of money. There may appear an excess or a deficiency of money in an individual’s cash holding. But such a condition can be remedied by increasing or decreasing consumption or investment. (Of course, one must not fall prey to the popular confusion between the demand for money for cash holding and the appetite for more wealth.) The quantity of money available in the whole economy is always sufficient to secure for everybody all that money does and can do.

Rothbard adds:

A world of constant money supply would be one similar to that of much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, marked by the successful flowering of the Industrial Revolution with increased capital investment increasing the supply of goods and with falling prices for those goods as well as falling costs of production.

According to the Austrian view, if the money supply is fixed, then economic growth will cause prices of real goods and services to drop, allowing people to purchase increasing quantities of goods and services with their money in the future. Such a world would indeed discourage immediate consumption, just like the Keynesians fear it would, but it would also encourage saving and investment for the future, when more consumption can happen. Since Keynesian economists exhibit little understanding of the concept of capital and marginal analysis, they imagine a decline in consumption as a calamity. If aggregate spending declines in high-time preference Keynesian economic models, workers will be laid off, which will in turn result in even less spending, which results in more workers getting laid off, and a continuous downward spiral that ends in destitution. Only active central governments spending liberally can forestall the Keynesians’ nightmare.

But to non-Keynesians—that is, to economists familiar with the concept of capital—a decline in spending is not just harmless, it is the basic bedrock of civilized society. It is only by reducing consumption and increasing saving that the deployment of capital is possible, as discussed in Chapter 6. To economists familiar with marginal analysis, a decline in the propensity to spend will cause a decline in spending at the margin, and not a complete suspension of consumption. Time preference is positive, as discussed in Chapter 3, and individuals always prefer consumption in the present to the future. Consumption in the present is necessary for survival. Individuals do not need to have the value of their money destroyed in order to consume; nature compels them to consume to survive. As saving for the future becomes more reliable, they may reduce their consumption at the margin, but they cannot abstain from consumption completely. This marginal reduction in consumption can result in a decline in marginal employment in the production of consumer goods, but not a complete collapse in employment. On the other hand, the decline in consumption of resources frees them from being used as consumer goods, and allows them to be utilized as capital goods. Saving money corresponds to saving economic resources from consumption, thus creating more opportunities for work to be directed at the earlier stages of economic production. A society which constantly defers consumption will actually end up being a society that consumes more in the long run than a low-savings society, since the low-time-preference society invests more, thus producing more income for its members. Even with a larger percentage of their income going to savings, the low-time-preference societies will end up having higher levels of consumption in the long run, as well as a larger capital stock. Far from bringing about destitution, the reduction of consumption is the only path to abundance.