Table of Contents

Labor

The employment of the physiological functions and manifestations of human life as a means is called labor… Man works in using his forces and abilities as a means for the removal of uneasiness and in substituting purposeful exploitation of his vital energy for the spontaneous and carefree discharge of his faculties and nerve tensions. Labor is a means, not an end in itself.

Every individual has only a limited quantity of energy to expend, and every unit of labor can only bring about a limited effect. Otherwise human labor would be available in abundance; it would not be scarce and it would not be considered as a means for the removal of uneasiness and economized as such.

– Ludwig von Mises

Labor and Leisure

Human time is the ultimate and scarcest resource. Spending it is irreversible, and its quantity cannot be increased indefinitely. Time’s scarcity and unpredictability create in humans a positive time preference: a preference for a present good over an identical future good. This preference applies to time itself. Humans value their present time period more than they value identical future time periods. This preference varies over time and from person to person, but it is nonetheless always present and always positive.

Humans can spend their time in two ways. The first involves doing the things we desire, like, and want to do for their own sake. These activities are subjectively valuable to the individuals who engage in them; they provide utility in their own right. They are, in a sense, their own reward. Economists refer to this use of time as leisure, which includes rest, time spent with loved ones, entertainment, recreation, and anything else an individual enjoys. Leisure is what you would do if you did not have to work. The second way to spend time is doing things for the sake of their results and outputs. This is the time man spends doing an activity that he does not find valuable in and of itself, but whose output he values. Economists refer to this use of time as labor, which Mises defines as “the employment of the physiological functions and manifestations of human life as a means.”

The distinction between leisure and labor is the distinction between what you want to do and what you have to do. Or, put differently, it is the distinction between what you do for its own sake and what you do for the sake of its future outcomes. If a person were engaged in an activity because they enjoyed it, regardless of its outcome, it would not be labor; it would be leisure. Labor itself has negative utility, or disutility, by definition; it reduces human satisfaction to engage in work, but man engages in it nonetheless because he expects it to produce outputs that offer him greater future utility. The present utility of leisure is sacrificed in favor of the expected future utility from the outcomes of the labor. The opportunity cost of labor is leisure forgone.

Humans have an infinitely high time preference when they are very young, as they are unable to conceptualize labor or anything but their immediate basic desires. As humans grow and mature cognitively, they realize they care about more than just increasing the value of their present time. As soon as children become capable of conceiving of the future and valuing it, they begin deferring instant gratification in exchange for future rewards. Our valuing of the future is what begins the process of lowering our time preference with age. With the ability to conceive of the future comes the ability to reason about it, plan for it, and work for it. Toilet training, or any activity carried out in anticipation of parental reward, might be the first activity that teaches a child to trade current present labor for future reward.

With maturity, a man transcends the narrow concerns of immediate gratification and begins economizing for the future. This takes two forms: economizing to lengthen the time period in which he is alive and economizing to provide for future time periods in his life. The human struggle to survive and thrive is the struggle to increase the amount and value of time we have on Earth, and it is inextricable from the need to work in the present. Surviving and prospering, in the long run, require work and sacrificing pleasure today, and this incentivizes the lowering of our time preference. When man values the return of labor more than the disutility of sacrificing leisure, man will work.

Man’s reason drives him to realize he can expend labor in the present to provide himself future utility, improve his future subjective well-being, and extend his life. No matter how favorable or unfortunate his circumstances, man will always think of ways to improve his situation. In a tropical paradise, in a desert, on a farm, or in a modern industrial society, reason will always find a way to direct man’s physiological functions and time toward improving his condition. There will always be present utility to sacrifice on the altar of future utility, and reason will always drive man to it.

The castaway stranded in an idyllic tropical island paradise might appear to modern people to be living the ideal life, but such a life will nonetheless inevitably involve labor. Man can be happy on the beach for a while, but as time passes, his contentment declines, and other needs arise. Time on the beach, like leisure in general, and like all goods with positive utility, exhibits diminishing marginal returns. The joy of the beach declines the more time the individual spends there. Other desires only intensify, as they go unsatisfied for longer periods. The castaway will soon get hungry, and his reason will lead him to conclude he can satisfy his hunger by working to secure food. His reason leads him to devise ways to transform wild animals into nutrition. He tries to catch a fish with his bare hands, or he hunts down rabbits and deer. There is no guarantee his toil will produce a worthwhile return, but hunger becomes more pressing as time goes by, increasing the urgency of the hunt, and decreasing the value of the leisure that would be attained without labor, thus incentivizing more, better, and smarter toil.

The motivation for work, ultimately, is that failure to do it, or failure to carry it out successfully, will result in death, sooner or later. Outside the Garden of Eden, man has always had to work to survive and thrive. At any point in time, each individual faces the choice between labor and leisure, as well as the choice of what kind of labor to perform to increase productivity. Labor is our first conceptual tool for increasing the amount and value of our time. Yet labor is not uniquely human. Instinctively, animals have the ability to engage in activities for which the rewards are not immediate, trading off present utility for future utility. Birds build nests, beavers build dams, and predators spend significant time chasing their prey. Unlike animals’ instincts, though, human reason can devise many other methods for economizing and increasing the productivity of our labor, discussed in the next chapters.

The primary way humans influence their surrounding environment is through the process of production. The following section defines the main terminology of production, which will be foundational to the rest of the book’s discussion.

Production

Production is defined by Mises as the “alteration of the given according to the designs of reason.” According to Mises, “These designs—the recipes, the formulas, the ideologies—are the primary thing; they transform the original factors—both human and nonhuman—into means. Man produces by dint of his reason; he chooses ends and employs means for their attainment. The popular saying according to which economics deals with the material conditions of human life is entirely mistaken. Human action is a manifestation of the mind.”

Labor is “the employment of the physiological functions and manifestations of human life as a means.” People work only when they value the expected return of labor more than the lost satisfaction brought about by the curtailment of leisure. To work involves disutility.

Consumer goods, final goods, or first-order goods satisfy human wants directly, independent of other goods. This is the end goal sought from the production process and the reason the process is undertaken.

Producer goods, intermediate goods, factors of production, or higher order goods are goods that satisfy human wants indirectly when used to produce consumer goods. Human labor can be viewed as a producer good, but this term is usually used to refer to capital. A capital good is any good that is acquired not to be consumed, but to produce other goods. The existence of a capital good requires the sacrifice of consumer goods.

Productivity is understood as the quantity of output produced by one unit of input in a specific period of time.

Exchange or trade: Willfully induced substitution of a more satisfactory state of affairs for a less satisfactory one. Production itself can be understood as an exchange of leisure time and capital inputs for the outputs of labor production.

Price: The thing that is given up in an exchange.

Cost: The value of the price; the value of the satisfaction one must forego in order to attain the desired end.

Profit, gain, or net yield: The difference between the value of the price paid (the cost incurred) and that of the goal attained. Profit in this primary sense is purely subjective; it is an increase in the acting man’s happiness, a psychic phenomenon that can be neither measured nor weighed.

Productivity of Labor

Man can work to produce products for himself, or he can work to produce products for others, receiving compensation in exchange for his time. Wage labor is distinct from performing a service for someone as a favor or gift, because the former involves compensation. Wage labor is distinct from slave labor in that it is voluntary; the laborer can stop working, and the employer can only seek to keep him by trying to convince him to return willingly through incentives such as better payment, better work conditions, or similar noncoercive means. Labor is, by definition, a consensual agreement between the employee and employer.

The decision of an employer to hire an employee is a market transaction, like all others. The difference between it and the exchange of a consumer good lies in the fact that employers do not value labor based on their own subjective preferences because labor is not a consumer good for the employer. Instead, since labor is a producer good, the employer values labor based on how much output it can produce, multiplied by the subjective valuation the market assigns to the product produced.

For the employer and employee to willingly agree on an arrangement to exchange labor for compensation, the conditions of the exchange must be satisfactory for both. For the laborer, this means his compensation is higher than the valuation he places on the alternative use of his time, which is leisure, or the next best available job. The value of the employee’s labor to the employer must also be greater than the wage paid, or else the employer would not pay it. At the margin, when an employer is deciding whether to hire an extra worker, she will only do so if the extra worker provides her with a marginal increase in revenue that is higher than the wage. Each extra worker must contribute to an increase in output production at the margin. The marginal increase in quantity produced is referred to as the marginal product of the worker. When that number is multiplied by the price of the product, we obtain the marginal revenue product, a measure of the revenue provided to the employer by the marginal worker. If the wage is higher than the laborer’s valuation of leisure or the next best use of his time and lower than the employer’s marginal revenue product, then the two can agree to work together for their mutual benefit. Otherwise, there will be no exchange of labor for compensation between the two parties.

Labor occupies a unique position in our world due to what Mises calls its “nonspecific character.” Unlike specialized capital equipment, human time can be directed toward all kinds of production processes. Capital that can no longer be productive in a specific line of business will likely be rendered obsolete, but human time can always be repurposed for more productive uses. There is always more demand for more human minds and hands to work in the world due to the ultimate scarcity of human time, and employers will always be willing to take the next worker at a wage lower than their marginal productivity.

Productivity is understood as the quantity of output produced by one unit of input in a specific time period. As discussed in the previous chapter, the value of human time has appreciated significantly throughout human history. Over time, labor wages continue to rise in real terms, because worker productivity continues to rise, driving employers to pay higher wages to obtain the labor they need and prevent it from going to competitors.

In the past 200 years, following the Industrial Revolution, the value of human time has continuously risen as humans have accumulated more capital, invented higher productivity technologies, utilized more powerful energy sources, and extended the division of labor to larger markets and more participants. All the inventions, tools, and technologies that increase human productivity have led to the extension of human lives and an increase in the value of human time, because now we need to be paid significantly more to part with our leisure. The end goal of economizing, after all, is to allow humans more, and better, time on Earth.

Unemployment

In the twentieth century, the concept of unemployment became closely intertwined with the concept of labor. Many schools of thought have posited that unemployment is an unavoidable and inevitable part of the workings of the market economy. Various reasons have been presented to explain why a free labor market will inevitably malfunction in a way that leaves significant numbers of people who are willing to work at prevailing wages unemployed.

But unemployment is as much a normal part of the labor market as burning crops is a part of the food market. As will be discussed in Section IV of this book, inflationary credit expansion and minimum wage laws are the root cause of unemployment. Inflation causes prices to rise, requiring workers to ask for higher wages to cover their increasing living costs. But since an increase in monetary media does not result in an increase in economic resources, employers often have no ability to pay higher wages to workers and remain operational. They will either lay off workers, or go out of business. Inflation reduces the wealth and holdings of both worker and employer and increases the price of the market goods they seek to purchase. Further, credit inflationism also causes the business cycle. The inflationary boom results in the financing of unsustainable investments, and their inevitable collapse causes entire economic sectors to witness bankruptcies, with large numbers of workers laid off and left with skills for which there is little demand.

As inflation causes unemployment through rising prices and recessions, governments and government-employed economists prefer to shift the blame onto the market economy itself or greedy capitalists, or they provide other flimsy explanations. Instead of tackling the inflation at the root of the problem, modern economists invariably propose counterproductive measures like minimum wage laws. Rather than a command for employers to pay workers more, minimum wage laws should be thought of as a prohibition against workers choosing the price of their own labor. Minimum wage laws prevent the market from adjusting to inflation, resulting in constant waves of unemployment that coincide with the business cycle.

It is telling that the concept of unemployment did not really exist as an economic term before the twentieth century. In a free market, people choose whether or not to work for the wage offered to them, so nobody can be involuntarily unemployed. With the introduction of monetary inflationism and minimum wage laws, a permanently unemployed part of the population became a fixture of modern economies, and blaming this unemployment on the market process became a fixture of the pseudoscientific economics dominant in modern academia, financed by those with vested interests in maintaining inflation in order to provide rationales for it.

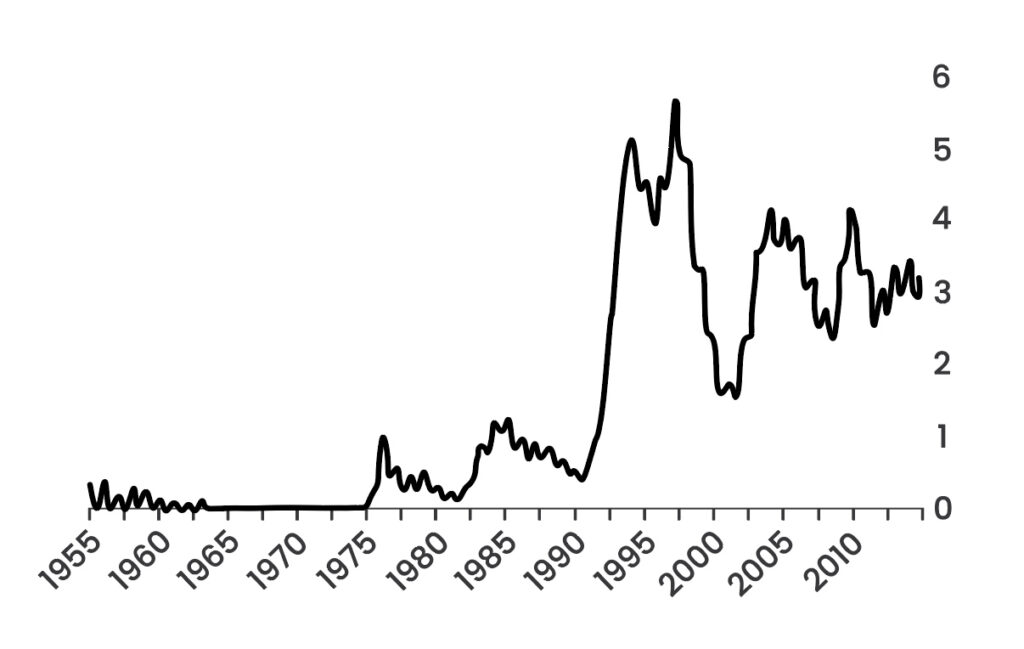

Switzerland, the last country in the world to go off the gold standard, provides a good example of this dynamic. As the fiat world struggled through severe unemployment crises throughout the twentieth century, Switzerland had practically no unemployment until it went off the gold standard in the mid-1970s. After adopting the dollar standard and engaging in inflationism, Switzerland has witnessed a rise in unemployment that follows the same cyclical pattern observed in every country that runs on fiat money.

Under a free market with sound money, savings appreciate in market value over time, and individuals have the freedom to work or not, and to ask for any wage they want. Employers also have the freedom to pay any salary they want. In such a world, with savings appreciating, it is perfectly rational for many to forego employment. A worker who cannot find employment at a prevailing wage is simply unable to find someone who values the marginal revenue product of his labor at a price higher than the worker’s valuation of leisure. The modern phenomenon of mass involuntary unemployment can only occur when there are laws, rules, or restrictions that make it illegal, and subject to punishment, to engage in labor at specific wage rates.

In the context of free exchange, there can be no such thing as unemployment among people who are willing to work, because this implies they are entitled to earn a wage that nobody is willing to pay them. The worker could always find work by increasing his productivity or decreasing his asking wage. Involuntary unemployment is impossible in a free-market economic system; it is the worker’s choice to ask for a wage that nobody is willing to pay, and thus it is their choice to remain unemployed.

Will Work Ever End?

Labor, as a resource, is very precious precisely because it competes with leisure for the scarcest of resources—human time. Further, as income and utility produced from labor increase, they lead to an increase in workers’ wealth; this results in workers who can afford to spend more time enjoying leisure, further increasing the disutility of their labor and discouraging them from working. Labor may be the only economic good or activity whose supplied quantity can decline as its price rises, because the increase in the price of labor causes an increase in the worker’s wealth, which might allow the worker to purchase more leisure and sell less labor. The scarcity of time means that the supply of labor has an opportunity cost that becomes more valuable the more a person earns from working. This dynamic has led many to speculate that economic progress might one day mean humans will no longer need to work.

Will we ever get to a point where we don’t need to work? This is a common fantasy among many politicians and economists who have no conception of the economic way of thinking, such as John Maynard Keynes and his many followers. Writing in the 1930s, Keynes speculated that productivity will continue to increase so much that by 2030, humans would only need to work a fifteen-hour work week to produce what they need. Keynes imagined technological progress would bring about technological unemployment, which he defined as “unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labor.”

“All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem,” Keynes concluded, because he naively imagines the economic problem is like a math problem that needs to be solved once to stay solved, as if it pertains to securing some specific set of goods and services needed for a happy life, and once these are secured, the economic problem is solved once and for all, and there is no longer a need for anyone to economize. But in reality, the economic problem is a permanent part of the human condition, as we are constantly facing choices between scarce objects, because that scarcity comes from our scarce and extremely valuable time. So long as humans are alive and need to decide what to do with their time, the economic problem exists, and humans attempt to solve it by working. There can be no final solution to the economic problem, only the replacement of bad choices with better choices.

“I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the economic problem may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within a hundred years… Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.” Keynes seems unaware that what he posits as a replacement to the economic problem is just the economic problem itself, but applied to choices slightly different from the ones he was used to seeing in the very few economic books he had read. Deciding how to occupy his time is man’s eternal and universal economic problem because time is scarce, and Keynes’ simplistic conception of economics prevents him from recognizing that use of time is an economic choice.

No matter how many material objects we have, we will always have a choice to make at the margin between immediate and future satisfaction. We can always forsake present satisfaction for more future satisfaction. There will never be complete satisfaction because human reason will always foresee a better possibility and work toward it. It would be very inexpensive for someone to live today by the living standards of Keynes’ day. Yet, even the poorest people today can use and own many things Keynes was never able to own. And they continue to yearn for a better living, as do the richest people. As long as humans economize, they use reason to produce new goods, services, and objects that others desire.

Keynes bases his fantastic vision of the future on the completely unjustified assertion that there are two types of needs, absolute and relative needs. Absolute needs, Keynes asserted, are needs felt “whatever situation of our fellow human beings may be,” while relative needs are felt “only if their satisfaction lifts us above, makes us feel superior to, our fellows.” Keynes posits that demand for the latter may be insatiable, but demand for the first class of needs could be completely satisfied. Keynes thought the economic problem has always been the primary and most pressing problem of the human race and the entire biological kingdom, and solving it would be a omentously important transformation of the nature of human life. He did not understand that the economic problem always exists for as long as human time is scarce and humans have choices to make. Even if humans were in an imaginary world where everything a person wishes for materializes in front of them immediately, the economic problem would not be solved, as humans’ mortality still forces them to economize their scarce time. The economic problem is solved every instant in which a human reasons about their time and makes a choice, only for a new economic problem to emerge in the next instant and force the same human to make another choice. The only final solution to the economic problem is death, the point at which there are no further choices to be made regarding time allocation.

As such, it is nonsensical to imagine, as Keynes does, that work could ever end, or the need for work could ever go away, or that abundance will reach a point where labor will not be needed. We are always economizing, and we always have to make choices between alternatives. As our living standards improve, our choices improve, but the act of choosing must remain, at least for as long as humans are mortal.

Is Labor Exploitation?

Are laborers exploited by capitalism? Millions of pages have been written on the topic of worker exploitation, based largely on the incoherent ramblings of Karl Marx, a semiliterate German bum who never had a job that could support him. Marx lived off the support of rich benefactors in England as he pontificated about reengineering the world into a dystopia run by people incapable of supporting themselves through their own labor.

Marxist economic analysis is based on the labor theory of value, discussed in Chapter 2. Since all economic goods require some labor input to transform them into economic goods that can serve our needs, the Marxist falsely concludes that labor is what gives economic goods value, and the quantity of labor that goes into the production of a good is what determines its value. This means the value of goods is based on the amount of labor that goes into producing them. Using the baseless assumption that economic value is imparted onto objects purely as a function of the amount of labor that goes into them, the Marxist automatically eliminates the value of the capitalist’s contribution. Workers need to turn up and work, whereas capitalists, as socialists maintain, do nothing. According to this view, because the worker does not receive the entire profit from the process of production, the capitalist is exploiting the worker.

This is obviously nonsensical because workers willingly choose to work for capitalists. Marxists do not attach any significance to the fact that workers willingly choose to sign up for this supposedly evil exploitation. As long as capitalists do not use violence or the threat of violence to force workers to work for them, then workers are willingly choosing to work, which indicates the work opportunity is the best option for spending their time. An observer or economist might resent this reality, but they cannot blame capitalists for providing workers with the best option available in exchange for their time. It is telling that Marxists who complain about this arrangement cannot offer workers better jobs than the capitalist “exploiters” offer.

But the understanding of work as exploitation betrays a deep ignorance of what capital and its value to economic production are. Capitalists defer consumption to provide capital for workers, which increases the workers’ productivity. At any point in time, the capitalist is choosing to forego consumption in order to provide workers with capital to increase their productivity. At any point in time, the capitalists can liquidate their capital goods and use the proceeds to finance consumption. By choosing to forego consumption and make the capital available to a worker, the capitalist is allowing the worker to have a higher productivity level. This higher roductivity makes the worker happy to receive only part of the proceeds. The alternative to capitalist exploitation is not just that the worker receives all of the revenues from the sale of the goods they produce; it is that the revenue is much lower without capital. A Marxist might consider a cab driver as being exploited by the owner of the car he drives, but that is only because the Marxist cannot conceive of what would happen if the driver denied the capitalist compensation for allowing them the use of their car. Without earning a return, the capitalist would prefer to use the car as a consumer good or sell it and consume its proceeds. Without the car, the driver would have to carry people on his back, which would be a highly uneconomical and physically destructive job. Only by allowing a capitalist to “exploit” him by providing him with capital (the car) is the job of a driver productive and safe enough to provide the worker with a good life.

The production process requires the worker to dedicate his time, but it requires the capitalist to contribute capital, which can only be acquired through previous work and can only be retained through continuous deferral of consumption throughout the entire production process. Without compensating the capitalist for her decision to delay gratification and invest, there would be no capital, and the worker’s productivity would decline significantly. The capitalist does not exploit the worker by taking part of his output forcibly; the worker willingly pays part of his output to the capitalist in exchange for securing a much higher productivity level.

The laborer-capitalist relationship is a feature of human relations that has existed in all human cultures, and it reflects a natural trade between an individual who has the ability to work but lacks the means to secure the necessary capital, and another individual who has more capital than she can, or wants to, utilize herself. The continued existence of this relationship is what incentivizes humans to accumulate capital, while pathologizing it and punishing it has led to societies experiencing calamitous economic destruction.