Table of Contents

Chapter 4 of The Bitcoin Standard discussed government money from a quantitative perspective, looking at its supply growth rates over the previous decades to compare with commodities and bitcoin. As a measure of the salability across time, the supply growth rate of fiat money in the second half of the twentieth century was found to be far higher than that of gold and silver, on average. However, The Bitcoin Standard did not delve too deeply into the details of the operation of the fiat monetary system, how it produces new monetary units, and how they are destroyed. This chapter will begin by explaining the dynamics of creation of fiat money through the process of lending, and how this process results in erratic and unpredictable supply growth. We will then examine how this supply translates to price increases and what their long-term implications are.

Lending as Mining

While a small percentage of a country’s currency is in fact in the form of physical cash, the majority exists in digital form. That money is created wherever a financial institution backed by the central bank lends. New money is not created when currency bills are printed, but rather whenever new debt is issued. Bill printing just turns some of the already existing currency reserves from digital to physical form.

Anyone who finds a way to get other people into debt profits not only from a positive interest rate return, but also by bringing new money into existence. Getting others into debt is the fiat standard’s version of gold prospecting. Rai stones were used as currency in Micronesia until Captain O’Keefe imported superior foreign technology to flood the market with new supplies. The monetary role of seashells was destroyed when modern industrial boating inflated their supply. Copper, silver, and gold miners constantly try to increase their supply, but gold’s indestructibility and scarcity combine to restrain its supply from growing too quickly. Bitcoin miners try to mine as much bitcoin as possible, but they are successfully constrained by the difficulty

adjustment and a network of thousands of nodes worldwide enforcing Nakamoto’s consensus parameters. On the other hand, politicians and bankers diligently find new excuses for extending credit in government money. Various political, constitutional, and intellectual safeguards against inflation have only sporadically, temporarily, and unreliably succeeded in controlling the debt creation underwritten by central banks. The most effective restraint against credit growth spiraling out of control in the fiat system has been the inevitable deflationary recessions it precipitates, and the concomitant collapses in the money supply.

Since lending is effectively the mining of new fiat tokens, there is a strong economic incentive to issue debt. Financial institutions stand to profit from creating new money, and a lending license is highly sought after. Politicians and bureaucrats also face strong incentives to encourage lending, as increased lending leads to increased investment and spending. According to the simplistic Keynesian economic model, which dominates the highest levels of politics and academia, increasing these factors in the short term is always the first solution to any economic problem. The short-term economic boom from credit expansion is all that a politician cares about, as the long-term consequences will likely be left for their successors to deal with. Moreover, these long-term consequences can always be blamed on convenient current scapegoats rather than obscure past credit policy decisions.

In 1912, Ludwig von Mises published The Theory of Money and Credit, a foundational text in economics. He summarized its central conclusion: “The expansion of credit cannot form a substitute for capital.” Since 1912, the fiat standard has provided object lessons for economists to point to in support of Mises’s contention. Capital consists of economic goods that can be used to produce other economic goods. Money can be traded for capital goods, but it cannot substitute for or supplement them. The stock of capital that exists in any society at any point in time can only be increased by deferring the consumption of existing resources. It cannot be increased by producing more claims on it.

Instead of accumulating capital from savers and lending it to borrowers, fiat banking just creates new claims on existing capital and hands them out to borrowers. There is little incentive for people to save, and there is no longer any real capital scarcity for those who are politically well connected. There is also no capital for those who are not well connected. Government fiat allows this form of banking to survive when it would not do so in a free market.

All that can be achieved from credit expansion is an increase in the perception of wealth in the minds of entrepreneurs, whose ability to acquire financing drives them to think they can secure the capital resources they need. However, since more credit is being produced without savers deferring consumption, the capitalists are in fact beginning a bidding war for fewer capital resources. As the bidding war escalates, the profitability of many of the capitalists’ projects evaporates, and their projects declare bankruptcy, defaulting on the credit they received from the banks.

Central banks have a pervasive influence over all banks allowed to operate in their respective countries. As such, the fiat standard leaves all of a society’s wealth and its monetary and financial system vulnerable to the central bank’s reckless monetary central planning and the shenanigans of individual financial institutions. One bank engaging in fraud and facing a bank run will not only cause repercussions for its own clients but also for other banks and their clients. Even perfectly solvent and profitable businesses would no longer be able to operate in a banking collapse because their financial counterparties would be compromised by liquidity crises. The fact that everyone is forced to use the same inflationary monetary asset leaves everyone vulnerable to its failure and makes the financial system as strong as its weakest link.

As these defaults pile up at the bust stage of the business cycle, the money supply begins to contract, threatening the financial system’s solvency. Should the liquidation of insolvent businesses continue, many of the banks that lent to them would necessarily go bankrupt. However, since banks have a monopoly on vital economic functions, their collapse is a catastrophe that politicians and the public want to avoid, leading to a clamor for the central bank and government to step in and inject liquidity into the financial system.

The reflationary logic is seemingly compelling. People’s livelihoods would be destroyed through no fault of their own, just because their financial institutions and counterparties in the financial system became insolvent. If the central bank already allocated reserves for the banks, and they can extend credit without causing a perceptible decline in the value of their currency, it would be cruel to just let these businesses and livelihoods go to ruin. Since the central bank can create liquidity at will by fiat, then relieving the liquidity crunch would prevent the destruction of many livelihoods. After all, the monetary policy of the monopolist central banks ultimately causes the recession stage of the business cycle, and none of these businesses have a choice in whether to opt into it. Opposing deflation and supporting reflation is also a surefire career-maker in politics and academia because it naturally finds large supportive constituencies among citizens and businesses.

A significant number of fiat economists have built entire careers and appointments at the Federal Reserve from supporting this position, which is exceptionally popular with governments, banks, and central banks. Milton Friedman’s A Monetary History of the United States was an elaborate labor of statistical huffing and puffing whose only piece of actionable advice was not to allow the money supply to contract during banking crises. His central conclusion was that the Great Depression was caused by the Federal Reserve not reflating the monetary system after the 1929 stock market crash. There is no mention of the causes of the crash in the expansionary monetary policy of the 1920s or in the highly unstable nature of fractional reserve banking built on top of an elastic currency not redeemable for gold. Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke wrote his dissertation on this episode as well, sharing Friedman’s conclusion.

After one hundred years of the fiat standard, a consensus has developed between academics and policymakers on the importance of preventing monetary contraction at all costs. However, without considering how credit inflation itself sets the scene for a deflationary credit collapse, this consensus is built on conceptual quicksand. The treatment is predicated on having to ignore the possibility of prevention and having to ignore the long-term impact of reflation, which is the fueling of future bubbles. And so, the fiat credit money system trudges along from one cycle to another, with inflationary bubbles and deflationary collapses following each other like the seasons. Each cycle misallocates much of society’s capital stock into unprofitable ventures that must be liquidated, with many lives upended in their wake. The business cycle shows how the fiat standard has a deflation as well as an inflation problem.

While these deflationary episodes are widely known for their terrible economic consequences, another of their oft-ignored implications is that they are a significant check on the growth and expansion of the money supply. Without these episodes purging large chunks of the money supply periodically, currency devaluation would proceed at a much faster pace. These recessions, and the foresight of central bankers, are a major reason why hyperinflation is not such a common occurrence in fiat monetary systems. In a fiat system, credit creation is, to some extent, self-correcting. While there were around sixty hyperinflationary episodes in the past century, and while these episodes are devastating, there is no denying that they have been exceptions rather than the norm during this period, the norm being variable inflation. Hyperinflation has usually appeared after significant government solvency problems and the monetization of government debt through the literal printing of large quantities of paper money.

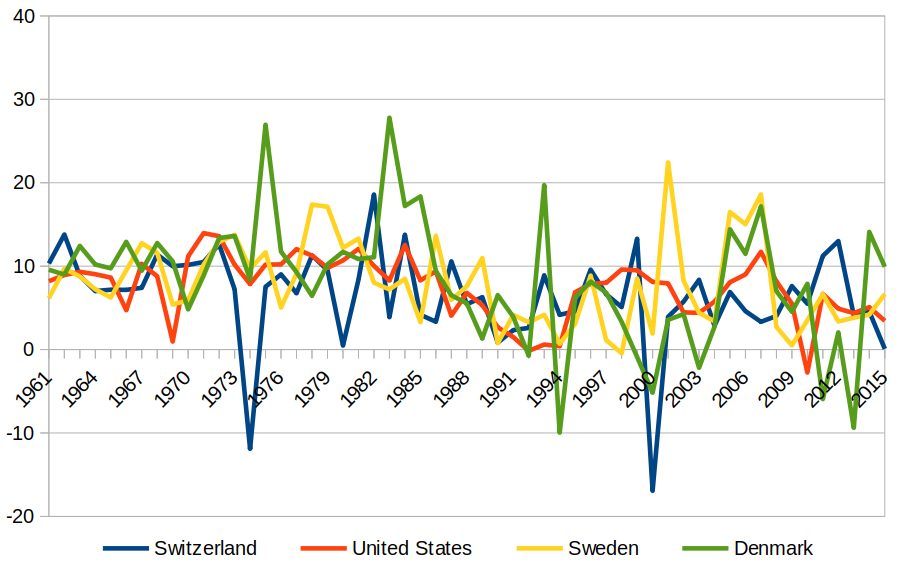

Data for 167 countries shows that the average annual growth rate of the money supply from 1960–2020 was 29%. Switzerland had the lowest average annual growth rate during this period, at 6.5% per year. The U.S. had the second-lowest annual growth rate, at 7.4%. Sweden had the third-lowest average annual growth rate, at 7.9%, and Denmark the fourth, at 8.2%. Of all the countries surveyed with full datasets, these four are the best poster children for low monetary inflation in the fiat standard.

Figure 3. Broad money supply growth rate for the four countries with the lowest average rate between 1960 and 2020.

Looking closely at their monetary supply growth rates from 1960 to 2015, we can see what the best-case scenarios for fiat monetary issuance look like. These countries not only had the lowest annual supply growth rates, but they also had relatively little variability in their growth rates.

Unlike with bitcoin’s perfectly predictable and auditable declining rate of supply growth, and unlike gold’s steady growth rate that averages around 1-2% every year, fiat’s annual growth rate is highly variable. Even for the four best-performing fiat practitioners, the supply can frequently increase by over 10% per year or turn negative at times because of the endless cycles of inflation, deflation, and reflation.

Deflation Phobia

The deflation phobia of modern economists and policy-makers has extended beyond just worrying about banking collapses. It has progressed to the pathological level where even the natural decline in prices caused by productivity increases is viewed as being economically catastrophic. There is a huge difference between recession-induced deflation, which is only possible with an inflationary credit collapse, and productivity-driven benevolent deflation. The latter is a healthy, normal, and sustainable feature of a free-functioning market system, where the good with the highest stock-to-flow and the reliably lowest rate of growth is used as money. As the monetary medium grows at the lowest rate of any market asset or commodity, its market price will likely rise relative to most goods over the long term. And as market participants engage in producing more goods, the quantities of all goods available are likely to grow faster than that of the monetary medium. Gold emerged as money because of its hardness, and so it appreciated in the long run against everything else under the gold standard.

Money thus tends to become more valuable in terms of real goods and services, and savers are able to enjoy more goods if they defer consumption. Declining prices are a natural market response to increases in the production of goods and services. Contrary to the argument presented by decades of fiat economists, the normal decline in prices caused by productivity-driven deflation does not have devastating consequences for society (although it does for their fiat jobs). The ability to buy more goods in the future does not stop people from consuming in the present. Time preference is always positive, and people always prefer having something in the present to having it in the future. Humans need to eat to survive, and most expect decent shelter, clothing, and other consumer goods, and so they consume. Deflation will likely cause them to reduce frivolous consumption, but they will consume nonetheless, and whatever they do not consume will be saved or invested, providing demand or goods in the future. Fiat economists understand the direction of the effect of moving to harder money correctly. However, they betray their ignorance of marginal analysis (i.e., comparing marginal costs with marginal benefits) when they conclude that a reduction in spending must somehow be total and catastrophic, rather than marginal and beneficial. People are more likely to hold on to their money if they expect its value to rise, but they will still need to spend it in order to survive. Harder money will result in a reduction in present spending, all else equal, but it will lead to more future spending.

The best example to illustrate this point is the computer industry, which even under inflationary fiat money makes products that become cheaper very quickly. In 1980, a one-megabyte (MB) external hard drive was worth $3,500, but in 2020 that amount of data storage was worth a fraction of a cent. And yet, people have continued to buy and benefit from hard drives for decades, even though their prices continue to decline. When making a purchase, one does not compare the price of the good to its future expected price, but rather the price of the good is measured against the benefit that can accrue from it. Even if the price of the good were to decline, the benefits of buying it today can outweigh the benefits of waiting, and if so, the buyer will make the decision to purchase a good. Every person who buys a phone or laptop today does so even though they would definitely get a lower price if they waited just one year. Yet every year, billions of people globally buy phones and laptops because they need them in the present, not just in the future. Life is finite, time preference is positive, people want to enjoy the benefits of production in the present, and Keynesian inflationary apologia cannot survive five minutes of intelligent inspection.

Human progress is intertwined with the hardening of our monetary media. The harder a monetary medium, the less its supply will be inflated, and the more its owner can expect it to maintain its value, or even have it appreciate over time. The more the money can be expected to hold its value over time, the more reliably an individual can use it to provide for their future self. The more reliably one can provide for their future self, the more they can reduce their uncertainty about the future. The less their uncertainty about the future, the less a person discounts the future, and the more they are likely to plan and provide for it. In other words, hard money is itself a driver of lowered time preference. As our money becomes harder, our ability to save efficiently increases, allowing us to provide for our future more easily and encouraging us to become increasingly future-oriented.

Throughout human history, competition between monetary media has reduced the value of the easier money and increased the value of the harder money. The effect has been a slow demonetization of easier monies and a continual progression to harder alternatives. Seashells, glass beads, rai stones, and salt gave way to metals that were hard to produce, and among the metals, the easier to produce and inflate gave way to the harder metals. Iron was demonetized thousands of years ago, copper hundreds of years ago, and silver began to lose its monetary role in the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, almost all of humanity was on a gold standard and able to store the value of its wealth in a money whose supply increases at around 2% per year, and whose value can be reliably expected to appreciate over time.

The introduction of fiat money stopped and reversed this seemingly inexorable progress toward ever harder money. The best money available in the world now increases in supply by around 7% per year. The ability to save value for the future is diminished, and the uncertainty of the future rises significantly. Greater future uncertainty and insecurity inevitably lead to a greater discounting of the future and a higher time preference.

CPI and Unitless Measurement

Fiat money enthusiasts maintain a strange obsession with a metric produced by national governments named the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Government employed statisticians construct a representative basket of goods and measure the change in the prices of these goods every year as a measure of price increases. There are countless problems with the criteria for inclusion in the basket, for the way that the prices are adjusted to account for technological improvements, and with the entire concept of a representative basket of goods.

Like many metrics used in the pseudoscience that is macroeconomics, the CPI has no definable unit with which it can be measured. This makes measuring it a matter of subjective judgment, not numerical precision. Only by reference to a constant unit whose definition and magnitude are precisely known and independently verified can anything be measured. Without defining a unit, there is no basis for expressing a quantity numerically, or comparing its magnitude to others. Imagine trying to measure anything without a unit. How would you compare the size of two houses if you could not have a constant frame of reference to measure them against? Time has seconds, weight has grams and pounds, and length has meters and inches, all very precisely and uncontroversially defined. Can you imagine making a measurement of time, length, or weight without reference to a fixed unit? The CPI has no definable unit; it absurdly attempts to measure the change in the value of the unit that is used for the measurement of prices, the dollar, which itself is not constant or definable.

The absurdity of unitless measurement covers up the fundamental flaw of the CPI, which is that the composition of the basket of goods itself is a function of prices, which is a function of the value of the dollar, and therefore it cannot serve as a measuring rod for the value of the dollar. As the value of the dollar declines, people will not be able to afford the same products they purchased before and will necessarily substitute them for inferior ones. Market prices result from purchasing decisions, but purchasing decisions are, in turn, influenced by prices. The price of a basket of goods is not determined by some magical “price level” force but by the spending decisions of individuals who can only spend the income they have. Purchasing decisions themselves are price-responsive and will adjust to changes in prices. The main and fatal flaw of the CPI, therefore, is that it is, to a large degree, a mathematical tautology and an infinite referential loop. This point is illustrated with an example in Chapter 8 on fiat food.

Beyond the actual change in the consumer basket of goods as a result of the change in prices, there is also the change in the composition of goods as a result of the judgment and motivations of the people in charge of defining the basket of goods. Economist Stephen Roach, who was starting his career at the Fed in the 1970s, has said then-chairman Arthur Burns fought inflation by removing from the CPI’s basket of goods items whose prices were rising, while always conveniently finding a nonmonetary story to explain the price increase. By the time he was done with it, he had eliminated about 65% of the goods in the CPI, including food and oil and energy-related products. The implications of these moves on the food and energy markets will be discussed in detail in Chapters 8, 9, and 10.

One of the most important ways in which the measurement of the CPI has been manipulated is through the removal of house prices from the basket of market goods, under the pretense that a house is in an investment good, an absurd redefinition. Investments produce cash flows, but a person’s own home cannot produce an income. On the contrary, it is consumed and it depreciates and requires continuous expenditure to maintain it. The fiat standard first destroyed the ability of individuals to save, then forced them to treat their home as their savings account. With low salability and divisibility, houses constitute terrible savings vehicles, but by excluding it from CPI, and teaching people to treat it as a savings account, inflation magically appears beneficial.

Inflation as a Vector

The CEO of Microstrategy, Michael Saylor, a newly converted bitcoiner, has given the best analysis of measuring inflation that I have come across. His key insight is that inflation cannot be measured as a metric; it can be better understood as a vector. There is no universal inflation rate that measures increases in the prices of all goods and services, as inflation affects different goods in different ways. If inflation is considered as a vector wherein each good has its own price inflation rate, it becomes far easier to identify the impacts of inflation on individuals and their provision for the future.

Saylor’s inflation vector allows us to see how inflation rates vary across goods depending on a few key properties, such as their variable cost of production and desirability. Goods that are abundant, not highly sought after, and require a low variable cost of production witness the least price inflation. With modern industrialization and automation driving costs down continuously, these goods are very good at resisting price rises since their supplies can be increased at a relatively small additional marginal cost.

Thinking about goods in terms of their variable cost of production can show their different price inflation rates. Digital and informational goods involve a variable cost of production that is close to zero. As Saylor puts it, if nobody turned up to work at Google tomorrow, their search engine would still continue to work, and the average user would only notice problems later as they stop making upgrades. Digital goods are likely to experience negative price inflation, as they always have done.

Industrial goods that can be produced at scale involve more variable costs than digital and informational goods. However, a very large percentage of their production costs are in original capital expenditure, not in variable running costs. These goods experience price inflation to some extent, albeit not very high. Industrial food is the best example of this. Even through all of the monetary inflation of the past decades, the price of a can of soda, a box of cereal, or processed food has increased very little. These goods have a low price inflation rate, in the range of 1–4% per year.

Goods that involve a significant variable cost, such as those involving extensive labor inputs, will be more sensitive to price changes than industrial goods. Organically farmed produce will be more sensitive to inflation than industrial food, and fine dining will be more sensitive to inflation than automated fast-food restaurants. Goods like this will witness higher levels of inflation than digital or industrial goods. As the level of skill involved in producing the good increases, the scarcity of the labor element increases, and the price inflation rate rises. The cost of hiring highly skilled labor increases much faster than the quoted CPI rates.

Another gradient along which the inflation vector manifests is scarcity, and this is where price inflation begins to appear more strongly. Inherently scarce goods manifest price inflation the most. House prices will appreciate faster than the prices of industrial products, and faster than the CPI, particularly as the latter does not include house prices, and the most desirable houses will increase in value the fastest. Property in desirable areas increases at rates that far exceed official CPI measures, and far exceed the price increases of properties in less desirable areas. Tuition in the top-ranked universities increases at similar rates to high-end property, along with luxury goods and artwork. Anything that commands some scarcity premium becomes an attractive store of value under fiat, attracting increasing demand. Whereas industrial goods can easily respond to increased demand with increased supply, scarce goods, luxury goods, and status goods cannot increase in supply and end up continuously rising in price. The price inflation rate for scarce and highly desirable assets is around 7% per year.

To add to Saylor’s categories, one could also add durability as a metric, along which the inflation vector varies. Durable goods are more likely to store value into the future, and thus they are more likely to attract store-of value demand and appreciate. Perishable and consumable goods will likely have lower price inflation than durable goods.

Saylor’s most brilliant insight on this issue is to pinpoint that inflation shows up in the cost of purchasing financial assets that yield income for the future. Returns on bonds have declined along with interest rates, reducing the ability of individuals to afford retirement. The market is effectively heavily discounting today’s money in terms of tomorrow’s real purchasing power as yields disappear. As the future becomes more uncertain, it is no wonder we witness a palpable rise in time preference.