Table of Contents

Fiat economists’ most commonly held misconception about bitcoin is that the network requires official, credentialed approval to continue to function. Government control of the monetary system and scientific funding has convinced generations of economists that reality is the product of fiat edict and given them a thoroughly top-down approach to understanding the world, where bureaucrats, scientists, politicians, journalists, and other positions of fiat authority are the enlightened vanguard of society who decide for the plebs how to live their lives. To this day, economists continue to engage in belabored theoretical discussions on whether bitcoin fits their preferred definition of money, whether it is worth the energy consumption, and whether it should be allowed to continue to exist. The longer bitcoin continues to operate, the more these concerns begin to look like the quaint superstitions of primitive tribes on first contact with modern machinery.

Bitcoin’s continued successful operation, its ability to perform final settlement internationally without requiring any government oversight, and its credibility at maintaining its monetary policy over twelve years all mean that it operates outside the realm of fiat authority, and delivers a shattering blow to the worldview of those who think reality comes out of fiat. Bitcoin does not need to convince fiat authority of its worth, it just needs to keep surviving on the free market by offering value to its users.

Bitcoin is the world’s first digitally scarce asset, and the first liquid asset with strict verifiable scarcity. It offers no yield and is therefore not held for its returns, like stocks. It is instead held for its own value, like cash. Austrian economists explain that cash is held because of uncertainty. In a world of no uncertainty, where all your future income and expenditures are perfectly predictable, there is no need to ever hold cash, as you can always place your money in capital markets to earn a return, which can be liquidated at the exact time you need to spend it. But in the real world, with uncertainty pervading life, people do need to hold cash balances to meet their uncertain future obligations. Investment in assets that offer a yield always involves risk.

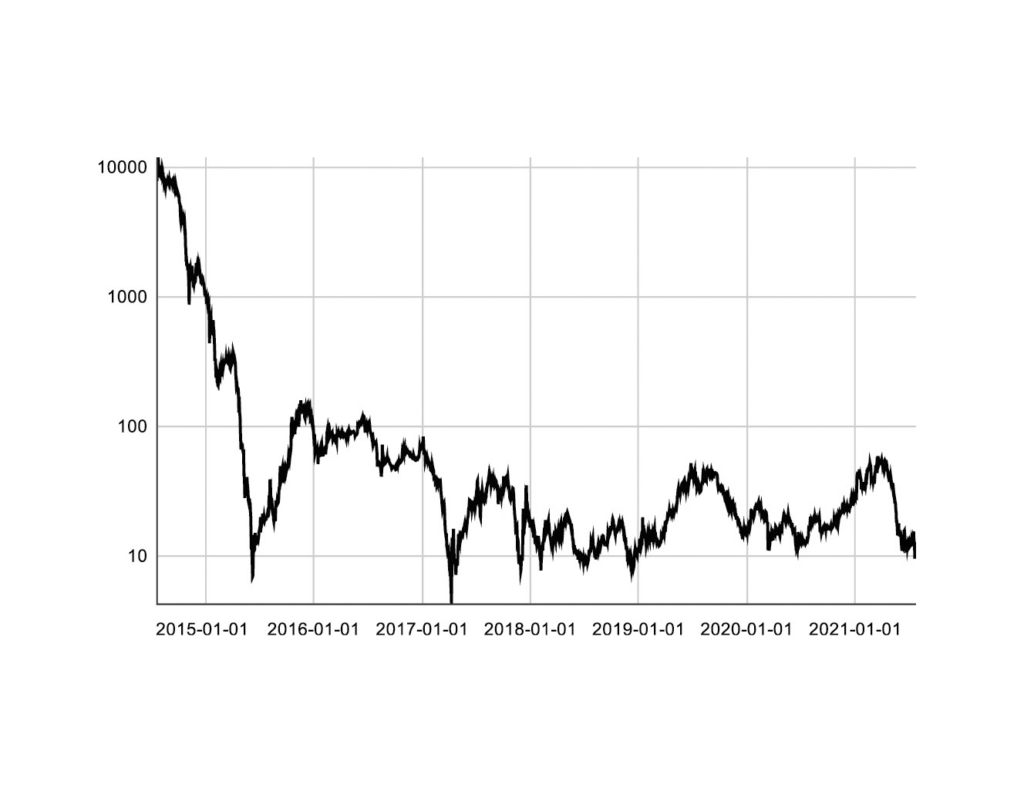

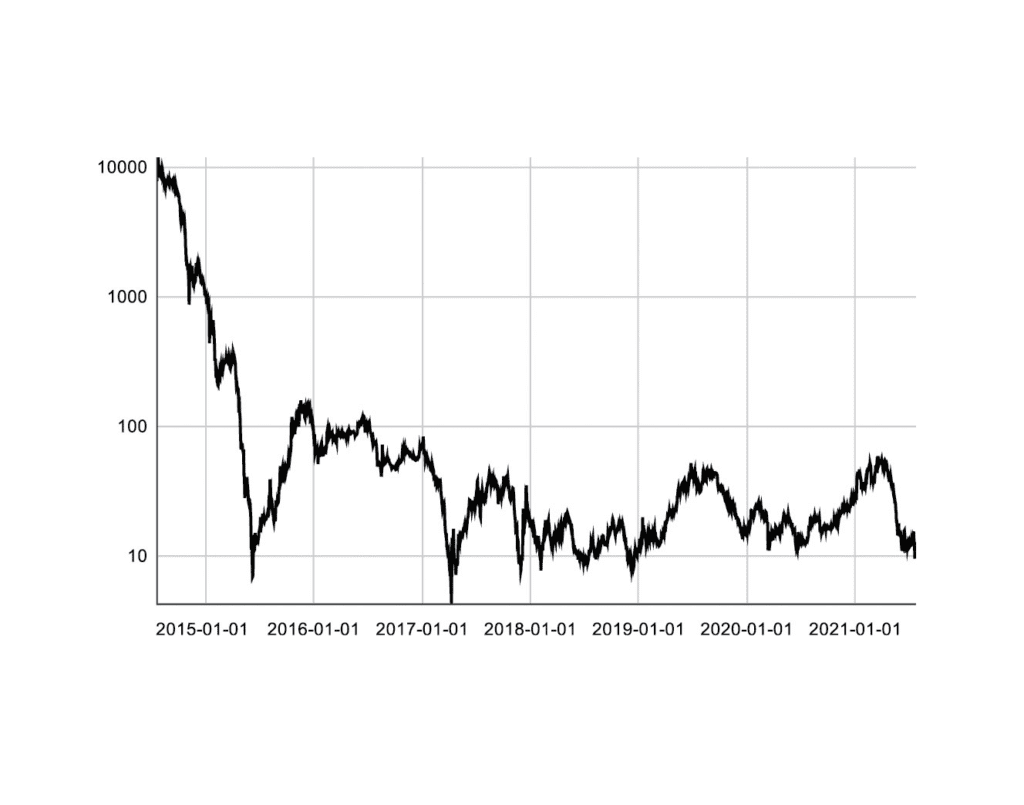

As discussed in Chapter 5, fiat’s inflationary nature has eroded its ability to function as cash, and as a result, people have sought several cash substitutes. People primarily hold government bonds, as well as physical gold, real estate, and equity as a way to recreate the ability of cash to save value for the future. Bitcoin is just another asset that can be added to this list. However, it differs from the other assets listed in that it can be accessed entirely outside the traditional fiat banking system and does not require legal, political, and regulatory oversight to function internationally. Bitcoin is also different from these other assets because its supply cannot be increased in response to demand. The supply of fiat credit, bonds, stocks, real estate, art, commodities, and all other kinds of cash substitutes can increase in response to increases in demand. This means that their roles as monetary media are inherently limited. Rises in their prices will inevitably cause oversupply and big crashes. Bitcoin’s scarcity means that its price crashes to continually and significantly higher levels than past prices. In its twelve years of existence, bitcoin has never been down over a four-year period. Except for one day, it has always been valued at more than fivefold its price four years earlier. Bitcoin’s four-year performance averages a 365-fold increase. Examining only the past five years of data, bitcoin has averaged a 26.05-fold increase over its price four years earlier.

One bitcoin block is expected to be produced around every ten minutes. Every 210,000 blocks, or roughly four years, the protocol halves the number of coins produced with each block. This means that the daily bitcoin production on any given day is half of what it was four years earlier. Four more years of successful operation will likely increase people’s awareness of bitcoin and increase the chances they place on its continued survival, thus increasing their subjective valuation and demand for it. So as long as bitcoin continues to operate, and its supply drops by half every four years, it is highly likely that marginal demand for it will be higher, and the marginal supply lower, than four years previously. This monetary time bomb keeps clicking with each new

block, and it is time for economists to begin to seriously contemplate what its continued clicking means for the world’s monetary and financial system.

The case for bitcoin as a cash item on a balance sheet is very compelling for anyone with a time horizon extending beyond four years. Whether or not fiat authorities like it, bitcoin is now in free-market competition with many other assets for the world’s cash balances. It is a competition bitcoin will win or lose in the market, not by the edicts of economists, politicians, or bureaucrats. If it continues to capture a growing share of the world’s cash balances, it continues to succeed. As it stands, bitcoin’s role as cash has a very large total addressable market. The world has around $90 trillion of broad fiat money supply, $90 trillion of sovereign bonds, $40 trillion of corporate bonds, and $10 trillion of gold. Bitcoin could replace all of these assets on balance sheets, which would be a total addressable market cap of $230 trillion. At the time of writing, bitcoin’s market capitalization is around $700 billion, or around 0.3% of its total addressable market.

Bitcoin could also take a share of the market capitalization of other semi hard assets which people have resorted to using as a form of saving for the future. These include stocks, which are valued at around $90 trillion; global real estate, valued at $280 trillion; and the art market, valued at several trillion dollars. Investors will continue to demand stocks, houses, and works of art, but the current valuations of these assets are likely highly inflated by the need of their holders to use them as stores of value on top of their value as capital or consumer goods. In other words, the flight from inflationary fiat has distorted the U.S. dollar valuations of these assets beyond any sane level. As more and more investors in search of a store of value discover bitcoin’s superior intertemporal salability, it will continue to acquire an increasing share of global cash balances.

Monetary status is an emergent outcome of market choice for monetary assets and not the result of economists’ theoretical appraisals of monetary properties. Modern economists have never contemplated the possibility that free-market competition could apply to money, the holiest of prerogatives for modern fiat governments that pay their salaries. With every passing day in which bitcoin operates to the satisfaction of its millions of users, the fulltime detractors and government-paid economists who constantly attack bitcoin begin to sound like deranged conspiracy theorists obsessed with stopping happy customers from wearing a shoe brand they like.

Bitcoin has grown from nothing to having nearly a trillion dollars of market value on global balance sheets in the space of twelve years. It has done so without a leader, without corruption, and without governments being able to stop it. In the past ten years, it has achieved an average compound annual growth rate of 215%. If it were to experience a similar growth rate in the future, it would overtake the $230 trillion benchmark by 2026. If it were to experience annual appreciation of only 20% per year, a tenth of what it experienced in the last ten years, it would arrive at the $230 trillion nominal valuation by around 2050. Rather than argue with ancient textbook definitions from the prebitcoin jahiliyya, economists would do far better trying to think in practical terms: How much can bitcoin continue to grow? What are the implications of its continued growth? This chapter examines some of the most common ways bitcoin could be derailed and then discusses how it would evolve if it were not derailed.

Government attacks

The most commonly discussed scenario for Bitcoin’s death is a government attack. Anyone who’s lived in the twentieth century has been conditioned to assume that anything government doesn’t like will be banned, and initially there’s little reason to suspect Bitcoin will be different.

Government attacks can come in many varied forms, some of which were discussed in The Bitcoin Standard. Rather than discuss the technical feasibility of these individual attacks, I will focus on what I view as the deeper underlying economic incentives that give bitcoin a chance to survive such attacks.

On a functional level, bitcoin is an extremely basic technological implementation that performs a very simple and easy task: the propagation of a block of transaction data usually of 1 MB in size (though it can be as much as 3.7 MB) roughly every ten minutes to thousands of network members worldwide. To be a peer on this peer-to-peer network, which allows you to validate your own transactions in accordance with the protocol’s consensus rules, all one needs is a device capable of receiving up to 3.7 MB of data every ten minutes. To merely send or receive a transaction without a node only requires a device that can send a few hundred bytes of data for each transaction.

Bitcoin is a far simpler and lighter program than Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, Netflix, or many of the popular online services that involve more extensive interactions and operations. The technical requirements for sending a few megabytes of data around the world continue to get cheaper and simpler as technology develops and the accumulation of capital in the computer and communication industries increases. There are currently tens of billions of devices worldwide capable of sending and receiving data, including almost all the world’s personal computers, smartphones, and tablets.

The common misconception many nocoiners have about how the internet works is that all these computers need to connect to some central server in order to access the internet, but that is simply not the case. The internet does not have a central hub that distributes content; it is simply a protocol that any computer can use to connect to other computers. As long as two devices can be connected to one another physically or through various mechanisms to transmit data, then the internet survives, and so can bitcoin. Were the internet a centralized institution, then shutting it down would be straightforward. Because bitcoin’s computing requirements are as low as they are, and the value held in it is large enough to motivate people to try their best to maintain the network, it is likely that bitcoin transactions and blocks would continue to be generated through any kind of ban.

As bitcoin continues to grow, attracting more attention from the technical community, developers will continue to innovate ways to transmit bitcoin data quicker and cheaper. Mesh networks and radio waves are two of the most interesting examples because they allow the use of the network even without a connection to the internet. Even the absence of internet-capable devices is now not much of an impediment, as it is becoming easier to join the network with any device that can send and receive data.

Bitcoin has found a way to make access to a hard form of money globally available at a much lower cost than the previous alternative, gold. Since hard money is a hugely important and beneficial technology, people also have a strong incentive to meet the costs of using this hard money. As time goes on, the liquidity and utility of bitcoin only increases, strengthening the incentive for people to use it.

Ultimately, if bitcoin provides value to its users, they will make sure they can access it. That motivation, more than any technical detail, is the real impediment to government attacks on bitcoin. History provides many illustrations of the power of economic incentives and their ability to repeatedly overcome government regulations. A good introduction to this can be found in the great book Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls: How Not to Fight Inflation. Bans and controls generally fail because government edicts cannot overturn economic reality; all they can do is change the economic cost/benefit of specific actions and cause people to adjust their behavior accordingly to still get the benefits while trying to avoid the costs. This is why price controls lead to shortages, black markets, queuing costs, violent conflict, and all manner of perverse and unintended consequences, but very rarely lead to achieving their intended goal.

A government clampdown would be far from a guaranteed way to destroy bitcoin. It would likely strengthen the network by advertising its real potential and value proposition to the world. Government attacks on bitcoin can only happen by restricting individual and financial freedom, the pursuit of which is the best reason to buy bitcoin. The simple statist mind assumes that reality is subject to government orders: “If government bans X, then X ceases to exist.” In reality, such government intervention just makes the provision of X much more profitable and increases the levels of risk people are willing to undertake in order to provide it. For example, a government order to stop banks from allowing their clients to use their balances to buy bitcoin might hurt demand for bitcoin in the short run, but it would signal to people everywhere that the financial sovereignty and censorship resistance bitcoin provides is extraordinarily valuable. Attempted bans would clearly communicate to people that the money in their bank accounts is not theirs to spend as they please; it is the government’s money, and it is limited to only government-approved uses. As this reality begins to sink in, more and more people will want to hold on to a monetary asset whose value is independent of government preferences and whims, and so the demand for bitcoin will likely rise (along with the profitability of supplying it).

The American war on drugs offers an instructive example. For almost fifty years, the U.S. government has killed and incarcerated millions of people in the U.S., Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan, and many other places in the world in a feeble attempt to stop drugs that can still be bought on the streets of every U.S. city. Drugs come from plants that usually need to be grown in sunlight, then processed and shipped around the world through a long network of suppliers before reaching the end consumers. Drug distribution is a far more complicated and demanding task than distributing bitcoin blocks, which do not need physical supply lines and can be transmitted using the simplest data transfer technologies. While drugs give their users a large incentive to consume and pay for them, it is still not as strong as the monetary and economic incentive to use bitcoin, which can be a matter of life and death for many people. With a stronger incentive than drugs, and an infinitely easier distribution mechanism, any government that tries to ban bitcoin has a tricky task ahead of it.

Another nontrivial obstacle for a government attack to overcome is that bitcoin has become ingrained in political and financial systems. Senator Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming is an open advocate of bitcoin, as is Congressman Warren Davidson of Ohio. Many other members of Congress have disclosed their ownership of bitcoin. Over the past five years, bitcoin has broadened its base in the U.S. and abroad. Its detractors may bemoan it, but its satisfied users continue to grow. It seems highly unlikely that members of Congress are going to pass laws against their own colleagues, families, and friends. Even bankers that viscerally and rabidly hate bitcoin are watching helplessly as their children’s interest in it grows. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon spent many years derisively dismissing bitcoin, but his own daughter bought bitcoin and outperformed his bank stock, and now his bank is offering it to their clients. Large public companies have started accumulating bitcoin reserves with the approval of regulatory authorities. Gary Gensler, the new commissioner of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has studied bitcoin extensively and has even taught a course on it at MIT.

Bitcoin now has a motivated and very vocal minority of the population interested in it. A motivated and organized minority is likely to get its way in U.S. politics for the simple reason that it cares more than other groups about its own issue. While people think of democracy as the rule of the majority, it is more accurate to think of it as the rule of the organized minorities. Corn farmers, for example, are a tiny fraction of the total population of the U.S. but still manage to get enormous subsidies. Although these subsidies are a cost to everyone else in the U.S., they are a small cost per head of the population; conversely, the benefit to corn farmers is massive, and they have every incentive to make it their prime voting and lobbying issue. From a politician’s perspective, supporting the corn lobbyists will get you votes and money, but going against them get you neither. Bitcoin’s motivated minority is growing into this kind of force in political systems worldwide. Any politician who attempts to clamp down on bitcoin will be faced with indifference by the vast majority of the population but strong opposition from bitcoiners. All of these developments suggest it is highly unlikely that the government could crack down on bitcoin in a similar way to its crackdown on drugs.

The Chinese government’s ban on bitcoin mining operations on its soil in 2021 provided a fascinating test of bitcoin’s resilience to government attacks. Most bitcoin miners operated in China at the time, and this was always viewed as a particular vulnerability of bitcoin. The ban had a discernible effect on the bitcoin network, as the estimated hashrate fell by some 50%, from around 180 exahash/second on May 14, 2021, to around 85 exahash/ second on July 3, 2021. The price also fell by more than 50% from its all-time high of $64,000 in mid-April to a low of under $30,000 in late July. This was likely the result of Chinese miners needing to liquidate their bitcoin holdings to relocate. The drop in hashrate resulted in the slowest average block time for any difficulty period in bitcoin’s history, thirteen minutes fifty-three seconds per block instead of the protocol’s target of ten minutes. As a result, the difficulty adjustment on July 3 of −27.94% was the largest downward adjustment in bitcoin’s history. This process powerfully illustrated bitcoin’s adaptability and robustness. As the number of miners attempting to solve the proof of work declined, the network slowed down, but the downward difficulty adjustment allowed block production intervals to return closer to the ten-minute mark. Around a half of the industrial capacity of the bitcoin network had to relocate internationally, and three months later, the result seems to be a slowdown in blocks, and a crash to levels that were at an alltime high only six months earlier. The price crash likely hurt many bitcoin investors, yet bitcoin was still roughly threefold its price year-on-year, hardly devastating for long-term holders.

So even a Chinese ban on bitcoin mining only caused a short-term crash in prices and a few weeks of slower blocks, after which time bitcoin resumed its normal service. Further, banning mining in China, the one country where miners were the most concentrated, led to the dispersion of mining capacity among nation-states, making the network less vulnerable to such an attack in the future.

Bitcoin might well be a genie that has grown beyond the ability of governments to put it back in its bottle. The secret is out. Millions of people worldwide have discovered this internet-native hard money and are interested in using it. The number of satisfied users continues to grow by the day. They are willing to invest time and effort into ensuring it continues to be available to them. Government clampdowns may inflict suffering on individual bitcoiners and perhaps cause short-term price falls, but it is doubtful they can derail the entire project.

Software bugs

Back in September of 2018, a bug was found in the code of Bitcoin Core versions 0.14 to 0.16.2 which could have allowed for increasing the total supply of bitcoins above 21 million. Had the bug been discovered by a malicious actor, they may have been able to use it to attack the network. Jimmy Song has provided a great analysis of this incident, and he suggests that although the likely ramifications of exploiting this bug would have created problems for the network, it was unlikely to have been fatal. Nonetheless, the episode made vivid one more type of threat afflicting bitcoin: malfunctioning code, or software bugs. Whether through an innocent mistake in the coding, or through the malevolent design of an attacker, it is not inconceivable that there could be problems with the Bitcoin code that could cause it to malfunction.

The threat of bugs and malfunction is far more serious for Bitcoin than for most other computer programs, because Bitcoin’s value proposition depends on its immutability, reliability, and complete predictability. If it is evolving to fulfil the role of digital gold, then the most important characteristic Bitcoin needs to copy from gold is its constant reliability and predictable supply. A bug that hinders the operation of the software or allows some users to create more coins would severely compromise the network and the likelihood of it continuing to succeed as digital gold. Rather than focus on the technical details of this bug and how it was fixed (which Jimmy’s article discusses), I would like to focus on how bitcoin’s open-source development counters this threat.

Linus Torvalds, the original creator of the Linux operating system, said that “with enough eyeballs, all bugs are rendered shallow.” That is a great explanation of the prime value proposition of open-source software. While open-source software usually relies on the efforts of volunteers who are not paid to be fully focused on the software, its collaborative nature can attract many people to review the code and improve it, which helps prevent critical bugs from emerging. This has proven to be a surprisingly successful and robust model. Whereas proprietary software development employs a few full-time, highly focused individuals, open-source development allows anyone to contribute and gives all users of the software the choice to adopt anyone’s contributions. The process of constant innovation, variation, and user selection creates a strong evolutionary pressure that drives the code’s improvement.

Open-source development is also a good example of Friedrich Hayek’s concept of spontaneous order, or order that emerges not through any preconceived individual design but through human action. Most market and societal institutions were not designed top-down by one individual. Instead, they emerged over many years through the actions and interactions of multitudes of individuals. Hayek argues that most of the human institutions that shape our lives, from language to customs to economics, ethics, and manners, are all emergent products of human action and not the conscious effort of human design.

This simple but powerful concept is helpful in understanding how bitcoin has continued to evolve after Satoshi left the project with nobody in charge. In the ten years since he has disappeared, the bitcoin software has improved significantly, and yet no single individual can possibly be viewed as responsible for these changes. While each change to the software can be viewed as a product of rational design by one or a few programmers, the choice of which changes get adopted by users, how the changes build on one another, and the general direction of open-source development are the complex and emergent result of the interaction of variations and individual choices.

There is no single person in charge of bitcoin or responsible for it. Bitcoin has voluntary users who choose to run open-source software at their own discretion; it is not the responsibility of the person who volunteered their time to build it. Bitcoin’s lack of central control, and the absence of a rational constructivist approach to its programming, is far from a disadvantage; decentralization is the most effective way for it to remain predictably neutral. This lack of central control also gives it a huge edge in dealing with software bugs, with a wide variety of users from all over the world examining the code and trying to find mistakes in it. This is the process that keeps all manner of open-source software running, as mentioned by Linus. In the case of bitcoin, the process has a powerful economic incentive for thousands of technically competent people who have a vested interest in it succeeding. Some of the best minds in software development are motivated to hunt for bugs merely

to protect the wealth they hold in bitcoin.

In other words, what ultimately protects bitcoin from software bugs is the economic incentive for its users to remove and deal with bugs as quickly as they emerge. And the 2018 bug is a good example of that. While it might have been theoretically possible for a well-funded attacker to exploit the bug, it was highly unlikely in practice due to the economic incentive for all bitcoin users to detect these bugs before they can be exploited. Attacking bitcoin offers very little economic reward, and so it is unlikely to attract the same number of users motivated to this end. An attack on bitcoin is destined to be a top-down design with a few focused and highly skilled individuals trying to execute it. Bitcoin’s defense consists of many thousands of users and coders who are constantly vigilant and defending the network against anything bad happening to it.

As Song concludes:

Bugs will always exist, but the important thing is to have a robust process for dealing with them. Open source software development has shown itself to be more reliable in the long run. Bitcoin adds to it strong economic incentives for many economic parties from developers to businesses to invest heavily in this process as well.

Beyond that, bitcoin’s extremely conservative and meticulous design ensures there is another layer of safety for dealing with any critical software failures: the ability to roll back the chain and return to the historical state before the bug struck. This would likely mean that any critical bug would be temporary rather than permanent. If one were to compare this to aircraft maintenance, it would be akin to having a function that allows you to return a crashing flight to its precrash state and perform maintenance on it, inconveniencing the passengers rather than killing them.

Provided bitcoin continues to operate successfully, its growth becomes likelier with each passing day. Any technology takes time to spread; most users will never become technically competent enough to understand all the nuances of its functioning. People need to see technology operating successfully, safely, reliably, and consistently for a significant period of time before they consider using it. Most people eventually got on airplanes, not because they studied jet aviation but because they had seen and heard of airplanes operating reliably, likely for years. Similarly, people will start to trust a digital form of storage, not due to an extensive study of bitcoin and cryptography, but rather after seeing it work reliably for years for others.

The Gold Standard

As discussed briefly in The Bitcoin Standard, the government policy that would likely be the most destructive to bitcoin would be the implementation of a gold standard similar to that at the end of the nineteenth century. All government restrictions on bitcoin are restrictions on financial freedom, and the desire to be free from government restrictions is exactly what creates demand for bitcoin. Given that the technical requirements for operating bitcoin are becoming increasingly simpler, government activities that aim to restrict bitcoin will inevitably result in greater incentives for people to overcome these restrictions.

Contrary to the statist instinct to want to ban anything that sounds objectionable, the more effective path for governments to undermine bitcoin would be to undermine the economic incentive for people to use it. However, this would mean increasing the financial and monetary freedoms that individuals have. The monetary system that would allow governments o maintain some form of monetary control while allowing the largest margin for a free market in money would be the adoption of the gold standard. In theory, a government could introduce a hard money standard with its own currency, and commit to not increasing the supply beyond a specific percentage. However, such a commitment would never be as credible as making government money redeemable into physical gold, offering everyone the ability to verify the gold backing, and tying the government’s hands.

A move to a gold standard would undermine all the drivers of bitcoin adoption, and it remains an open question whether, in such a world, demand for bitcoin would be enough to prevent attacks and secure the network. Gold currently has a far larger liquidity pool than bitcoin. The value of all aboveground gold is around $10 trillion, more than ten times the value currently stored in the bitcoin network. This very large pool of liquidity means that gold currently has more salability than bitcoin. In other words, for someone looking to buy or sell something, the probability that they will find a counterparty for that trade willing to pay or accept gold is larger than the chance of finding someone willing to pay or accept bitcoin. A move to gold would be far more palatable for the majority of the world’s population since they either own gold or currencies backed by gold.

Moving to a gold standard would curtail the ability of governments to intervene in the banking system and protect incumbents from outsiders. This would likely unleash innovation and experimentation in financial systems, as it has done throughout human history, and it is not difficult to imagine the development of highly convenient payment technologies backed by gold. There is no reason why any of the modern payment innovations developed for fiat money and digital currencies could not be implemented on top of gold with 100% reserve backing. The cost of gold final settlement would be far higher for governments than settling fiat liabilities, and the effect on government budgets would be too devastating politically for any politicians to attempt. Were modern fiat governments endowed with a low time preference, they might conclude that the pain of voluntarily adopting a gold standard today would be less severe than a future where they lose monetary status to bitcoin completely. But that seems fanciful to any observer of modern governments.

Politically, culturally, and intellectually, there seems to be little chance of a gold standard adoption. Modern political institutions, academia, media, and public opinion are largely shaped by Keynesians and statists. The monetary role of gold is viewed with scorn and disdain among most educated and influential members of society. The influence of corporate interests that benefit from easy money is far too strong to imagine any kind of constructive monetary reform emerging from the political process.

Bitcoin, however, is a hard monetary system that can gain adoption whether or not the entrenched easy-money interests approve of it. And even a readoption of the gold standard would likely only delay the inevitable move to an internet-native money with higher spatial and intertemporal salability. Gold will soon have a lower stock-to-flow ratio than bitcoin, and it will continue to have a much higher cost of transfer. Even if the adoption of bitcoin slows considerably and there are significant crashes in its price, the slow increase in its supply will still make it likely to recover and appreciate in the long run and hold its value better than gold.

The above analysis does not constitute an ironclad prediction of bitcoin’s inevitable success, but it should at least suggest that its continued long-term survival is a distinct and realistic possibility. So how would bitcoin grow in a fiat world?

Central bank adoption

Could central banks adopt bitcoin as a reserve asset? Nothing inherent to bitcoin would make such adoption impossible. The case for it is clear: if bitcoin increases in price, any country that uses it as a reserve asset will witness its international cash reserve account rise in value, which would make it less likely for their government or central bank to run into balance of payment problems. The more the reserves appreciate, the more leeway the government has with its own spending and international payments. Further, adopting bitcoin allows central banks to engage in international payment settlements with other central banks, financial institutions, and foreign exporters without needing to resort to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s global payment settlement infrastructure, avoiding the risk of sanctions and confiscations. This is likely most appealing to countries at odds with U.S. foreign policy. The threat of other nation-states holding bitcoin reserves first could in itself encourage governments to make the first move. Geopolitical rivals accumulating a harder currency would likely increase their spending power.

In 2021, El Salvador was the first country to adopt bitcoin as legal tender. As a dollarized economy, El Salvador had no seigniorage revenue to lose by adopting bitcoin. El Salvador also stands to gain from the large number of its citizens who work in the U.S. using bitcoin Lightning apps for remittances. It remains to be seen how successful this move is for the people of El Salvador and their government, and whether that encourages others to follow suit.

There are several reasons to suspect this is a move that will not be quickly imitated by major central banks. The first reason is that if we understand bitcoin as an alternative to central banking, then central banks are clearly the last institutions that need it. Central banks are the institutions that provide the services that bitcoin most closely approximates, and so they will likely remain the last to see the value of an alternative to their services.

The second reason is that while countries like China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and others may hate the U.S. dollar-based global financial system, they love having their own fiat currencies far more than they hate the dollar. The dearness with which central banks treasure their ability to inflate their respective country’s money supply could act as a strong constraint against moving to a bitcoin standard. China, Russia, and Iran may like to make a lot of noise about the unfairness of the U.S. dollar monetary system and how it privileges the U.S. internationally, but these governments are not run by sound money economists who would like to see a return to the nineteenth-century gold standard. Decades of Western cultural imperialism mean that even these countries are ruled by the kind of leftist, socialist, Keynesian, and similarly inclined economists who idolize inflation as the key to solving all of life’s problems. These governments do not oppose fiat money; they just hate other governments’ fiat money. They recognize that their extremely elaborate states and bureaucracies, with far-reaching control of their citizens’ lives and large monopoly industries to benefit them and their cronies, are utterly dependent on their ability to continue creating their own money.

We know this because while these countries have long talked about shifting to gold for international payment settlement and as a reserve asset, they have never done it. While they have accumulated gold as a hedge against their dollar reserves, they refuse to settle their own trade using gold and continue to rely on fiat networks. It is doubtful that it is merely the cost of gold settlement that is preventing these governments from moving to a gold standard. It remains to be seen whether bitcoin’s superior salability across space and value appreciation will tempt governments where gold failed.

Aside from the self-interest of the ruling elites in these countries, U.S. power is another important factor that may stop them from adopting gold. The IMF has long banned its members from tying their currency to gold. The U.S. still has the world’s strongest military and the strongest currency, and any global financial crisis that happens, while having its root causes in the dollar, is likely to only make the dollar stronger, not weaker, as happened in 2008. For all its flaws, the dollar is still the most liquid of all national currencies, and the one bearing the lowest default risk. All other central banks have liabilities in the dollar.

Another reason you might not expect central bank adoption of bitcoin is that modern central bankers have only managed to obtain their jobs by being so completely and thoroughly inculcated with Keynesian and statist propaganda economics that they will be the last in the world to understand the viability and significance of bitcoin as an alternative to what they do. The fiat mental baggage makes the central banker the last person capable of understanding that money does not need the state, and the last person to get the significance of bitcoin.

Finally, understanding bitcoin’s value proposition as a long-term store of value despite its short-term fluctuations requires a certain degree of low time preference, which you cannot expect to find in abundance in modern government bureaucracies. The uncertainty and short-term nature of democratic rule instills a short-term orientation in these bureaucrats, and all but guarantees that politics is a short-term power and money grab. Politicians or bureaucrats can be expected to rationally prioritize their self-interest in short periods in office over their constituents’ long-term future. Chapter 1 of Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s masterpiece Democracy: The God That Failed contains an excellent discussion of this point.

This book’s analysis of the debt mechanisms of fiat suggests one more reason why bitcoin might prove attractive to central banks: the monetization of a present good allows individuals and firms to hold on their balance sheet a liquid asset independent from the risks of the credit market, reducing their dependence on central bank monetary policy. The conundrum of today’s central bankers is that they are at once asked to provide the accommodative monetary policy for government spending and private sector expansion, while also having to ensure savings and investments do not devalue too much.

Will some central banks choose to outsource some of the demand for savings to the neutral apolitical bitcoin network, which is unaffected by credit market dynamics? Or will they try to maintain as much wealth as possible in their own network to finance government spending through devaluation?

While El Salvador provides a compelling counterargument, several reasons suggest it is likely bitcoin will continue to develop as described in the subtitle of The Bitcoin Standard: A Decentralized Alternative to Central Banks.

Monetary Upgrade and Debt Jubilee

The most widely held prediction about how a bitcoin economy develops usually involves the entirety of the world economy collapsing into a heap of hyperinflationary misery, similar to the one you see in Venezuela today. The dollar, euro, sterling, and all other global currencies would collapse in value as their holders drop them and choose to move their capital to the superior store of value that is bitcoin. Governments would collapse, banks would be destroyed, global trade supply lines would come crumbling down. But there are several reasons to be optimistic that this may not be the case.

The first reason is that the hyperinflationary scenario assumes the collapse in demand for national currencies would lead to their values collapsing. But historically, hyperinflation has always been the result of a large increase in the money supply and not a sudden decline in money demand. The demand for rai stones, glass beads, seashells, salt, cattle, silver, many national currencies, and various other monetary media did drop over time as market participants introduced harder alternatives. However, that decline would likely be gradual unless there was a quick increase in the money supply. Hyperinflation can only happen as a result of governments and central banks increasing the money supply, as a close study of any and every modern case of hyperinflation would show.

In Venezuela today, the local currency has dropped to less than a millionth of its value just a few years ago. Venezuela the country is still there, and the size of its population is the same as before the currency collapse. Venezuelans still need money and are demanding more of it. Demand for holding the bolivar has dropped significantly, but demand for local currency units could not possibly have dropped to a millionth of where it was. Venezuelans still need the currency to settle all their government-related business, an ever-growing occurrence thanks to the socialization of the economy. The only way to understand the bolivar’s collapse in value is as a result of the rapid increase in supply; any reduction in demand was rather an effect, not a cause, of that currency’s value dropping. Venezuelan money supply statistics show the supply of the bolivar increased by a multiple of one hundred between 2007 and 2017, at which point the Venezuelan government stopped publishing money supply figures, suggesting an even more significant increase. Similarly, in Lebanon, the central bank has increased the supply of physical bills and coins by around 650% in the last two years, while the currency has plummeted by more than 90% against the U.S. dollar.

To understand the likelihood of a hyperinflationary collapse, we need to focus on the nature of fiat money creation. Should fiat money continue to function as discussed in Part 1, with lending as the equivalent of mining, the likelihood of hyperinflation is reduced by two forces. First, it is not easy to quickly expand credit to a hyperinflationary degree, and second, credit expansion is self-correcting because it brings about financial bubbles that liquidate large amounts of the money supply. The business cycle is the brutal and highly inefficient fiat equivalent of bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment: if credit expands too quickly, it causes speculative bubbles in particular sectors of the economy, like the stock market, housing, or high-tech sector. As investments in these sectors increase, assets become overpriced, beyond what the fundamentals of their balance sheets imply. This incentivizes the production of more financial assets, causing the price of the assets to eventually fall, liquidating a lot of loans and contracting the money supply. Should this dynamic continue, bitcoin’s rise alone is unlikely to cause hyperinflationary collapses. If hyperinflation were to happen, as it is happening in Venezuela and Lebanon today, it would be the result of governments overriding the credit creation process and resorting to increases in the base money, most likely through physical money printing, or its modern digital equivalent, through central bank digital currencies. If the credit nature of fiat money is preserved, it could avoid hyperinflationary collapse even if bitcoin continues to consume more of its share of money demand.

Secondly, it is instructive to think about the impact of the rise of bitcoin on the process of fiat money creation. Bitcoin does not just compete with fiat currency for cash asset demand, it also competes with fiat debt. The devaluation of fiat money drives demand for debt instruments that are not exposed to equity risk and which offer returns that compensate for inflation. The demand for a store of value is what leads to the enormous issuance of debt. If more individuals and companies start to hold bitcoin instead of debt instruments on their balance sheets, that would reduce the demand for credit creation, reducing fiat money creation, making hyperinflation less likely. By undermining the incentive to hold debt instruments, bitcoin actively combats the inflation of the fiat money supply.

Thirdly, bitcoin has a similar effect on the incentive to borrow. In a world of artificially low interest rates and easy fiat money that is expected to constantly devalue, individuals are likely to borrow rather than save. The discovery of bitcoin gives individuals and corporations the chance to save in a hard asset that appreciates over time, making them less likely to need to borrow to meet their major expenses.

The fourth reason we can expect there to be no hyperinflationary collapse as a result of the rise of bitcoin is that hyperinflation happens when the entire monetary system of a society collapses, thus destroying the complex web of calculations and interactions that coordinate the activities of individuals across a large modern society. A modern society relies on money as the medium in which prices are expressed, and these prices are what coordinate economic activity and allow individuals to calculate what to produce and consume. No modern society, with its sophisticated infrastructure, is possible without a highly complex division of labor, dependent on the price mechanism and economic monetary calculation, to coordinate economic activity. The collapse of money destroys this division of labor and makes economic coordination impossible, unraveling modern life into a primitive disaster. But all of this happens when the only monetary system of a society collapses, and in a fiat standard, local government fiat is the only monetary system available to people in any given country. Historically, as national currencies have collapsed, citizens have usually not had an available monetary alternative with salability across space and time. Governments experiencing hyperinflation do not just allow their banks to offer banking services with foreign currencies. When they do, such as in the case of the dollarization of Ecuador, hyperinflation ends, and economic production, growth, and normalcy resume on a harder money.

Due to its superior salability across space, bitcoin is much harder to ban than foreign national currencies. It also offers a refuge from hyperinflation rather than being the cause of it. As a national currency collapses, any citizen can shift their wealth to a growing pool of liquidity with which they can trade, allowing economic production and calculation to proceed and averting a humanitarian catastrophe. Should bitcoin become widespread enough to destroy demand for government currencies, then the network will be large enough to support an increasing amount of coordination, trade, and investment. Unlike in a hyperinflationary scenario, a move to bitcoin without a large increase in the supply of government money would not lead to a catastrophe; it would be a global upgrade—a peaceful technological upgrade of society’s monetary infrastructure. Anyone who wants to keep using government money can continue doing so, but as bitcoin undercuts both its demand and supply, the government money bubble shrinks and withers away, while the bitcoin economy grows.

Rather than a threat that can destroy fiat money, bitcoin may turn out to be the neat technological solution that allows fiat to unwind peacefully. Bitcoin simultaneously reduces fiat demand and the incentive to create more fiat supply. It is like someone skillfully and neatly dismantling the fiat house of cards into a deck of cards by removing each set of two cards leaning on each other at the same time: the card of fiat demand and the card of fiat supply.

If governments of advanced economies, which have done a semi-respectable job in managing their currencies over the past few decades, manage this process wisely, they would allow the credit and money contraction to happen naturally. The fiat-denominated economy would continue to shrink in relation to the bitcoin economy as more people upgrade to the superior, harder, and faster monetary asset. The fiat monetary system could operate for the next fifty years in the same way it has operated for the last fifty. But by the end of the next fifty years, it may well be a tiny fraction of the size of the bitcoin monetary system. Rather than go out with a bang, the current global monetary system would just slowly and naturally get downsized into irrelevance as its currencies lose their value, and market share, to bitcoin.

Rather than an attack on the fiat system, bitcoin might allow the fiat economy an exit from its spiral into ever-more debt slavery, as it devalues the fiat debt that saddles everyone in the fiat system. If more people move to bitcoin, and fiat-denominated debt devalues in real terms, the vast majority of the world’s economy benefits enormously from the devaluation of its obligations. The sooner one upgrades to the bitcoin economy, the sooner their fiat debts become insignificant.

In a world where the possibility of saving were available again, you would expect a growing portion of the population to be free of debt and to have enough savings to finance their expenses, as well as to finance their businesses. Fewer people would resort to loans in order to buy cars, houses, or consumer goods because they could save up for them in hard money. More interestingly, perhaps, would be the shift in business financing, as more people become wealthy enough to finance their own businesses with their own savings rather than from bank credit. Bitcoin truly has the potential to transform the current mass of debtors into entrepreneurs, and the consequences of this for human flourishing and prosperity are scarcely imaginable.

Under sound money regimes, a free market in capital emerges in place of central monetary planning. Productive individuals are able to accumulate capital and watch it appreciate in value, and so they can finance themselves and their businesses. Productivity is rewarded with compounding growth in value over time, giving the holders of capital more of it, and thus placing increasingly more capital in the hands of the productive.

In large, centrally planned, credit markets, such as those that exist under government money, capital is centrally allocated by government bureaucracies that determine who gets new capital, devaluing the capital accumulated by the productive members of society. In such a world, being productive is punished over time, and credit financing is more likely to go to those who can afford to brace the bureaucratic hoops of government credit boards. Firms grow larger to afford lawyers and PR firms to communicate their stability to creditor banks, and smaller businesses become less viable. This is why firms tended to be smaller under the gold standard, and far more smaller businesses thrived. It is said that when Britain was the prime industrial global force, its average factory had twenty workers. A free market in capital would similarly encourage the development of a diverse array of smaller firms, as opposed to rent-seeking megacorporations, and these smaller firms would serve as laboratories for a multitude of inventions and innovations. It is no wonder that the golden era of innovation in the nineteenth century, la Belle Époque, ran on a hard money. That hard money is what allowed many inventors and tinkerers the capital and freedom to experiment with outlandish ideas. The Wright brothers were two bicycle shop owners whose savings allowed them to experiment with flight and change the world.

The rosy transition scenario for bitcoin is that it leads to a growing parallel monetary and financial system which offers its adopters significant benefits for upgrading to it. Individuals, businesses, and local governments are likely to gradually migrate to this monetary system. Eventually, the only part of the economy that would remain wedded to government money would be government itself, and the parts of the economy dependent on government money, both of whose contribution to valuable economic production is approximately zero. But this is not a foregone conclusion.

Speculative Attacks

A counterpoint to consider to the preceding section’s analysis is the impact of the strategy of borrowing dollars to buy bitcoin. While many people would be tempted to exit fiat debt entirely and shift to holding hard bitcoin savings, the continued existence and wide availability of fiat debt will offer a strong incentive to borrow fiat and use it to accumulate bitcoin. One of the smartest and most farseeing analysts of bitcoin, Pierre Rochard, had identified this scenario as early as 2014. He outlined how bitcoin allows investors worldwide to carry out a speculative attack on all national currencies, similar to what George Soros and beneficiaries of low interest rate lending have been doing to weak national currencies for decades with spectacular success.

The speculative attack is, then, the natural evolution of what inevitably results when easy money meets hard money, amplified by the force of fiat credit. The speculative attack strategy is to borrow the weak currency and use it to buy the stronger currency. Borrowing the weak currency causes an increase in its supply, and selling it for strong currency causes a decrease in demand for it, which results in the decline of the value of the weak currency next to the stronger currency. This reduces the value of the weak money loan the attacker owes, while increasing the value of the hard currency he holds—a highly lucrative combination. Because bitcoin is a harder currency than all national currencies, it could be the perfect vehicle for attacks against national currencies.

As large corporations and financial institutions are now accumulating bitcoin while also borrowing large amounts of fiat, a speculative attack is arguably brewing, even if its participants may be unaware of what they are doing. As these public companies with significant treasuries watch their bitcoin balance grow in nominal value, their balance sheets become stronger, allowing them to take on more fiat debt, increasing the supply of fiat, and providing them more fiat with which to buy more bitcoin. The profitability of this move can be understood as the market rewarding the move to the better monetary asset. How far can these speculative attacks go?

A couple of restraining forces can be identified. Corporations are now finding it easy to borrow on capital markets as they accumulate bitcoin, but only because of the very large amount of capital looking for debt obligations without equity risk. As bitcoin investment becomes more accessible to institutional investors, many of these lenders will choose to just purchase bitcoin instead of lending to financial firms that purchase bitcoin, limiting the credit available for launching speculative attacks.

Should private lending decline because of the rise of bitcoin, credit is likely to become even more centralized and government-controlled. As lending becomes more politicized, it would not be a surprise to see fiat governments restrict lending to any entities with bitcoin on their balance sheets. The centralization and politicization of credit in the hands of governments undermines the possibility of speculative attacks, but it also undermines the credit nature of fiat, rendering it more of a digital version of ubiquitous government papers that have been the hallmark of hyperinflation.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

Between starting to write this book and its completion, the tone of central banks toward bitcoin has changed completely. In 2018, the average central banker would have summarily dismissed bitcoin by muttering irrelevant references to apocryphal tales and folk songs about the prices of tulip bubbles rising in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.113 In 2021, central bankers are racing to implement what might be the most important upgrade to the fiat network in five decades: bitcoin-inspired central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

Central bankers present CBDCs as a technologically progressive step that allows for faster and more secure digital payments. However, their transformative potential for surveillance, political patronage, and economic central planning is under advertised. CBDCs would give central banks full real-time surveillance capabilities of all citizens’ wallets and spending. CBDCs would also allow governments to tax and pay their citizens more directly and effectively, increasing the efficiency by which governments disrupt the workings of the market economy. As the popularity of government handouts surges in the postpandemic world, CBDCs offer a great product-market fit for governments looking to distribute large amounts of money to their citizens.

Whereas the current fiat system allows all lenders to mine fiat into existence by issuing loans, CBDCs will likely centralize this process in the hands of the central bank. With all balances held at the central bank, and credit increasingly politicized and centralized, the fiat system would take a very decisive turn toward an authoritarian and socialist society. CBDCs might herald the end of fiat as credit money generated through loans, and transform it into a pure digital commodity money issued by the central bank, with important implications for the rise of bitcoin. As the corrective mechanism of fiat credit bubbles collapsing is sidestepped by the move toward fiat noncredit CBDCs, the brakes on fiat inflation would be severed. CBDCs would continue to increase in supply as governments indulge in fiat-century spending habits, but there would be no credit collapses to reverse the increase. The orderly monetary upgrade scenario becomes less likely.

Since the 2008 financial crisis and the increased intervention of fiat central banks into financial, credit, housing, and many other markets, fiat central banks have been overriding the correcting mechanism of money supply collapse. An increasing share of the world’s bond and stock markets is now held by central banks, and their valuation is increasingly determined by central bank fiat, with the normal workings of the credit cycle overruled through infinite quantitative easing.

The 2020 global pandemic crisis resulted in most governments engaging in increased payments to their citizens under various guises, and clamor is growing for turning these into regular Universal Basic Income payments. CBDCs would allow for the implementation of such inflationist schemes with high efficiency, allowing for increased central planning of market activity. Government spending would proceed unabated by whatever little discipline credit markets currently exert. Real-world prices are likely to rise, which would lead to more control over economic production to mandate prices.

CBDCs are perhaps most devastating for the banking sector, which would increasingly get disintermediated in the pervasive relationship between government and serf. The closest analog to the operation of the CBDC is the Gosbank, the State Bank of the USSR, which was the only bank in the Soviet Union from the 1930s until 1987. All citizens who had bank access had access to only one bank, and it decided on all economic decisions. Limiting the role of private banks, or eliminating them in favor of money generated by pure government fiat, is likely to lead to a highly centrally planned economic system with tight government control over all aspects of economic life.

If inflation is a vector, as explained in Chapter 4, CBDCs will likely lead to a fast rise in the price of highly desirable and scarce goods, while industrial goods will likely witness small declines in price, and digital goods will continue to get cheaper. The same tricks of the 1970s can serve to maintain inflation in a politically desirable range: skewing the composition of the basket of goods used to measure CPI to favor goods with low price inflation, and directing consumers toward these choices through the use of fiat incentives. As we have seen since the 1970s, price inflation will drive political pressure on citizens to reduce consumption of nutritious food and high-power sources of energy. The growing popularity of these narratives in fiat academia and media in recent years suggests they are very likely to become the subject of government and monetary policy.

Government CBDC fiat is likely to finance more fiat science to find fault with meat and hydrocarbons, our most reliable technologies for nutrition and power, and thus the most price-sensitive products. We can already see how the old religious narratives about energy and food, discussed in Part 2, are becoming increasingly popular as inflation causes the prices of food and energy to rise. As access to money and banking becomes centralized, this power can be very conveniently wielded to prevent official CPI numbers from looking bad through heavy taxation, rationing, or an outright ban of the purchase of certain goods. The push to promote fiat foods and fuels will likely take a far more coercive turn with the implementation of CBDCs. The past year has also shown how public health concerns can contribute to this totalitarian monetary control: lockdowns are increasingly looking like a permanent feature of the modern fiat economy, small businesses are being destroyed, savings are devaluing, and citizens and businesses are increasingly dependent on government spending to make ends meet.

The Soviet Union continued to produce very impressive numbers for economic growth into the late 1980s, even as Soviet citizens were going hungry thanks to shortages. In the same way, modern government-run central banks can project an illusion of wealth despite a contrary reality. Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus, two of the most important postwar economists in the U.S., both of whom have won the Bank of Sweden Prize (commonly misidentified as a Nobel Prize), wrote in their 1989 Economics textbook, which is standard issue for most undergraduate students around the world, “The Soviet economy is proof that, contrary to what many skeptics had earlier believed, a socialist command economy can function and even thrive.” Modern macroeconomics shares Soviet macroeconomics’ faith in the ability of high priests with PhDs to divine and optimize the working of an economy through models, metrics, and statistical analysis.

Central banks’ increasingly monopolistic control over economic affairs and statistics allows them to produce numbers that can mask and embellish the economic reality for the majority of the population. The likely outcome for the sclerotic, propagandized economies surrounding governments is a slow terminal decline into irrelevance, similar to what happened to the Soviet economy. Ultimately, the structures for these shambolic organizations can remain, but they will become hollow and less attractive to the people who follow their own self-interest to a new economy. While government- connected firms may continue, they will lose their relevance and value.

In this kind of scenario, the bitcoin-based hard money economy would grow, and more holders of that hard money would witness an appreciation of their wealth. At the same time, government-based economies would shrink, both in size and in relative wealth, as the widespread emigration of society’s productive class punishes centrally planned economies. The fiat economy will continue to provide people with lucrative careers and alluringly large fiat-denominated salaries, but increasingly fewer quality, scarce, and desirable goods. As the producers of economically valuable goods move to a harder monetary standard, these fiat-denominated monetary units will buy less, as people trade the valuable fruits of their labor for the harder currency. Fiat-denominated monetary units will continue to maintain a semblance of value only when used to purchase mass-produced economic goods.

You can imagine two new global economies emerging across the world. On the one hand, there is the easy money, centrally planned economy of which government, media, and academia insist you must be a part. It provides comfortable jobs secured from competition and controlled prices to ensure everyone gets their government-recommended soy, bug, and high fructose corn syrup rations, stays in a tiny home, consumes little energy, and has few or no kids to avoid burdening the planet with inconvenient inflationary pressure. And on the other hand is a growing, innovative, and apolitical economy which draws in the most ambitious, creative, and productive people in the world to work hard on providing goods of value to others.

As the fiat mining process becomes increasingly centralized and monopolized by central governments, economic and political power will also follow. Those who are well-connected to the digital printer will likely be the only ones who can afford the highly desirable goods whose prices are increasing most rapidly, while the vast majority witness their purchasing power, wages, and investments failing to keep up with inflation. Centralized inflation will create a monetary caste system similar to that which exists in socialist societies: a ruling class with an abundance of desirable goods, and a majority surviving thanks to a black market.

In this dystopian world, the black market is bitcoin, and it affords the serfs a superior monetary asset to what their government offers. It is common to hear CBDCs discussed as an alternative to bitcoin, but a clear examination of the nature of the two shows that CBDCs are the best advertisement for bitcoin. They are superficially similar in that they are both digital, but importantly, their fundamental characteristics are stark opposites. Bitcoin makes payment clearance a mathematical and mechanical process that cannot be controlled by intermediaries, whereas CBDCs make every transaction subject to approval and reversal by the central bank. Further, bitcoin makes monetary policy mathematically certain and free from any human tinkering, whereas the raison d’être of central banks is to dictate monetary policy. As essential goods like fuel and meat become increasingly difficult to acquire using centralized currencies, and as operating businesses will entail heavy compliance costs to access banking services, the appeal of bitcoin will only grow. As inflationary monetary policy causes the value of CBDCs to decline, bitcoin’s contrasting ability to appreciate in value will shine.

The growth of purely fiat CBDCs will make an orderly upgrade to a harder money less likely and instead will probably result in economic apartheid between two hostile monetary systems: bitcoin and fiat. The fiat economy will be fully regulated and surveilled, constantly subject to inflationary pressure, and financing increasingly violent and totalitarian governments that control their serfs’ purchasing decisions. The bitcoin economy would be a free market based on hard money, allowing its sovereign members to save, trade, and plan for the future freely while financing the growth of cheap energy production worldwide.