Table of Contents

Money, being a part of every economic transaction, has a pervasive effect on most aspects of life. The mechanics of fiat money outlined in the first section of this book create several distortions significant to food markets. This chapter focuses on examining two particular distortions: how fiat’s incentives for raising time preference affect farmland production and food consumption choices, and how fiat government financing facilitates an activist government role in the food market through interventionist farm regulations, food subsidies, and dietary guidelines.

1. Fiat farms

In 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon appointed longtime government bureaucrat Earl L. Butz to serve as secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Butz was an agronomist who also sat on the boards of various agribusiness companies. His stated goal was to bring food prices down, and his methods were brutally direct: “Get big or get out,” he told farmers as low interest rates flooded farmers with capital to increase their productivity. This was a boon to large-scale producers but the death knell for small farmers. Butz’s strategy killed small-scale agriculture and forced small farmers to sell their plots to large corporations, consolidating the growth of industrial food production, which would in due time destroy America’s soil and its people’s health. While increased production did lead to lower prices, they came at the expense of the nutritional content of the foods and the quality of the soil.

The large-scale application of industrial machinery can bring down the price of industrial foods, which was what Butz sought. Mass production leads to an increase in the size and quantity of the food and its sugar content, but it is much harder to increase its nutrient content as the soil gets depleted of nutrients from repetitive intensive monocropping, requiring ever-larger quantities of artificial fertilizer to replenish the topsoil.

The quality of food has degraded over the fiat years, as has the quality of food included in governments’ favorite broken measure of inflation, the Consumer Price Index, the invalidity of which is discussed in Chapter 4. The absence of an objective definable unit makes the measure meaningless and hides the fact that the composition of the basket of goods used as the reference will change in response to changes in the value of the currency it purports to measure. Food provides the best example of this dynamic.

As prices of highly nutritious foods rise, people are inevitably forced to replace them with cheaper alternatives. As the cheaper foods become a more prevalent part of the basket of goods, the effect of inflation is understated. To illustrate the point: imagine you earn ten dollars a day and spend it all on eating a delicious ribeye steak that gives you all the nutrients you need for the day. In this simple (and, many would argue, optimal) consumer basket of goods, the CPI is ten dollars. Now imagine one day hyperinflation strikes, and the price of your ribeye increases to one hundred dollars while your daily wage remains ten dollars. What happens to the price of your basket of goods? It cannot rise tenfold because you cannot afford the one-hundred-dollar ribeye. Instead, you make do with the chemical shitstorm that is a soy burger for ten dollars. The CPI, magically, shows zero inflation. No matter what happens to monetary inflation, the CPI is destined to lag behind as a measure because it is based on consumer spending, which is itself determined by prices. Price rises do not elicit equivalent increases in consumer spending; they bring about reductions in the quality of consumed goods. The change in the cost of living cannot, therefore, be reflected in the price of the average basket of goods, since the basket declines in quality with inflation. This gives us an understanding of how prices continue to rise while the CPI registers at the politically optimal level of 2–3% per year. If you are happy to substitute industrial waste sludge for ribeye, you will not experience much inflation!

This move toward substituting industrial sludge for food has helped the U.S. government understate the extent of the destruction of value in U.S. dollars and the devastating consequence this has had on its unfortunate users. By subsidizing the production of the cheapest foods and recommending them to Americans as the optimal components of their diet, the extent of price increases and currency debasement is less obvious. A closer look at the historical trend of the U.S. government’s suggested dietary guidelines since the 1970s shows a continuous decline in the recommendation of meat and an increase in the recommendations of grains, legumes, industrial oils, and various other nutritionally poor foods that benefit from industrial economies of scale. The industrialization of farming has created large conglomerates with significant political clout that have become a powerful part of the political landscape in the U.S. According to OpenSecrets.org, a website that tracks political contributions in U.S. elections, large agribusinesses gave federal office seekers more than $193 million in the 2020 election cycle. Perhaps this helps explain why, for seven decades, industrialized farming operations have had so much success lobbying for increased subsidies and dietary guidelines that encourage Americans to buy their products.

2. Fiat diets

The second link between nutrition and monetary economics pertains to the impact of government dietary guidelines. The rise of the modern nanny state, which role-plays as caretaker of its citizens and attempts to provide all the guidance they need to live their lives, could not have been possible under the gold standard, simply because governments that start making centralized decisions for individual problems would quickly cause more economic harm than good and run out of hard money to keep financing their operation. Easy government money, on the other hand, allows for government mistakes to accumulate and add up significantly before economic reality sets in through the destruction of the currency, which generally takes much longer. It is thus no coincidence that the government-approved dietary guidelines came into existence shortly after the Federal Reserve’s creation had begun the U.S. federal government’s transformation into the nation’s iron-fisted, gun-toting nanny. The first such guideline, focused on children, was issued in 1916, and the next year they issued a general guideline.

The short-comings of centrally-planning economic decisions have been thoroughly detailed by Mises and the Austrian school, primarily in the economic context, but the logic is equally applicable to nutrition decisions. Mises explained that what coordinates economic production, and what allows for the division of labor, is the ability of individuals to perform economic calculation over their own property. When the individual can weigh the costs and benefits of different courses of action they might undertake, according to their own preferences, they are able to decide the most productive course of action to meet their own ends. On the other hand, when decisions for the use of economic resources are taken by people who do not own them, there is no possibility of accurate calculation of the real alternatives and opportunity costs, particularly as they pertain to the preferences of the individuals utilizing and benefiting from the resources.

Humans, like all animals, have an instinct for eating, as anyone who has seen a baby approach food will know. Humans have developed traditions and cultures around food for thousands of years which help people know what to eat, and individuals can experiment themselves and study the work of others to decide what to eat to meet their goals. But in the century of fiat-powered omnipotent government, even the decision of what to eat is increasingly influenced by the actions of central governments.

Government agents making decisions about food subsidies and dietary and medical guidelines are, like the economic central planners Mises critiqued, not making the decisions purely from the perspective of every individual eating in the country. They are, after all, employees with careers heavily influenced by the government fiat that pays their salary. That political and economic interests would influence their supposedly scientific decisions is only natural. Three main driving forces have created today’s modern government dietary guidelines: governments seeking to promote cheap industrial food substitutes to hide the price increases of real foods, the revival of a nineteenth-century movement that sought to massively reduce meat consumption for religious reasons, and industrial agricultural interests trying to increase demand for the high-margin, nutrient-light industrial sludge.

In The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath, Robert Samuelson recounts the story of how desperately President Lyndon Johnson had attempted to fight the rising prices of many economic goods.42 Of the many harebrained and economically destructive ideas he had, what was most striking was that in the spring of 1966, he called on the U.S. surgeon general to issue a phony warning against the consumption of eggs when their prices spiked. In other words, Johnson asked a federal bureaucrat to concoct a fraudulent health scare around perfectly nutritious food for reasons that had nothing to do with science.

For theological reasons outside the scope of this book, the Seventh-day Adventist Church has for a century and a half been on a moral crusade against meat. Ellen G. White, one of the founders of the church, had “visions” of the evils of meat-eating and preached endlessly against it (while still eating meat secretly, a very common phenomenon among antimeat zealots even today). There is, of course, nothing objectionable about religious groups following whatever dietary visions they prefer, but problems arise when they seek to impose those visions on others. Under a fiat standard, the political process allows for enormous influence on national agricultural and dietary policies. Seventh-day Adventists are generally influential members of American society, with significant political clout, and many successful individuals are in positions of power and authority.

The Soyinfo Center proudly proclaims on its website:

No single group in America has done more to pioneer the use of soy foods than the Seventh-day Adventists, who advocate a healthful vegetarian diet. Their great contribution has been made both by individuals (such as Dr. J.H. Kellogg, Dr. Harry W. Miller, T.A. Van Gundy, Jethro Kloss, Dorothea Van Gundy Jones, Philip Chen) and by soy foods-producing companies (including La Sierra Foods, Madison Foods, Loma Linda Foods, and Worthington Foods). All of their work can be traced back to the influence of one remarkable woman, Ellen G. White.

Another member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, Lenna Cooper, went on to become one of the founders of the American Dietetics Association (ADA), an organization that still holds significant influence over government dietary policy. The ADA is responsible for licensing practicing dietitians. In other words, anyone caught handing out dietary advice without a license from the ADA could find themselves thrown into jail, financially ruined, or both. One cannot overstate the influence that such a catastrophic policy has had: the government granted a monopoly on dietary advice to zealots with a religiously motivated agenda that was totally divorced from the human body’s needs and the entire planet’s dietary traditions. The result has been the complete distortion of many generations’ understanding of which foods are healthy. Even worse, the ADA is responsible for formulating the dietary guidelines taught at most nutrition and medical schools worldwide, meaning it has shaped the way nutritionists, doctors, and chefs (mis)understand nutrition for a century. American adults interested in eating a healthy diet, as opposed to the diet recommended by official government-approved guidelines, are free to ignore the decrees of federal bureaucrats posing as scientists, although they will still be influenced by the economic distortions. American schoolchildren, however, are not. In the government-run schools of America, following federal health guidelines is a legal requirement, and school cafeterias adhere to them religiously. At the same time, politicians have made schools responsible for feeding children not just lunch, but also breakfast, dinner, and even summer meals. Millions upon millions of American kids are being compelled by the government to consume a fiat diet. While statists proudly believe they are fighting poverty by having the state supply this fiat food for children, they are actually impoverishing them long term by setting them up for years of health problems in adulthood. While American children pay the price with their bodies, industrial food producers soak up taxpayer-funded profits.

The reader should not be surprised that the ADA, like all other main institutions of progressive government control of the economy and citizens, was established in 1917, around the same time as the Federal Reserve. Another organization, The Adventist Health System, has been responsible for producing decades’ worth of shoddy “research” used by advocates of industrial agriculture and meat reduction to push their religious visions on a species that demonstrably can only thrive by eating animal proteins and fatty acids.

The messianic anti-meat message might have been drowned out in a sane world, but it was highly palatable to the agricultural industrial complex. The crops which were to replace meat in the messianic visions of the Adventists were easy to produce cheaply at scale. It was a match made in heaven. Agroindustry profited enormously from producing these cheap crops, governments would benefit from understating the extent of inflation as citizens replace nutritious meat with cheap slop, and the Adventists’ crusade against meat would provide the mystic romantic vision that would make this mass poisoning appear as if it were a spiritual step forward for humanity.

The confluence of interests around promoting industrial agriculture products is a great example of the ‘Bootleggers and Baptists’ nature of special interest politics, described by economist Bruce Yandle. While Baptist priests were evangelizing the evils of alcohol and priming the public to accept these restrictions, it was the alcohol bootleggers who lobbied and financed politicians to impose prohibition, as their profits from bootlegging would increase with the severity of the restrictions on alcohol sales. In so many matters of public policy, this pattern repeats: a sanctimonious quasireligious moral crusade demands government policies, the most important consequence of which is to benefit special interest groups. This dynamic is self-sustaining and self-reinforcing and does not even require collusion between the bootleggers and Baptists!

With fiat inflation causing both the cost of nutrient-rich food to rise and the increased power of government to meddle in dietary affairs, with a religious group attempting to commandeer government diet policy for its own antimeat messianic vision, and with an increasingly powerful agricultural industrial complex able to shape government food policy, the dietary Overton window has shifted considerably over the past century. What passed for healthy food came to include a long list of toxic industrial materials. It is entirely inconceivable that the consumption of these “foods” would have been as popular without the distortions generated by fiat money.

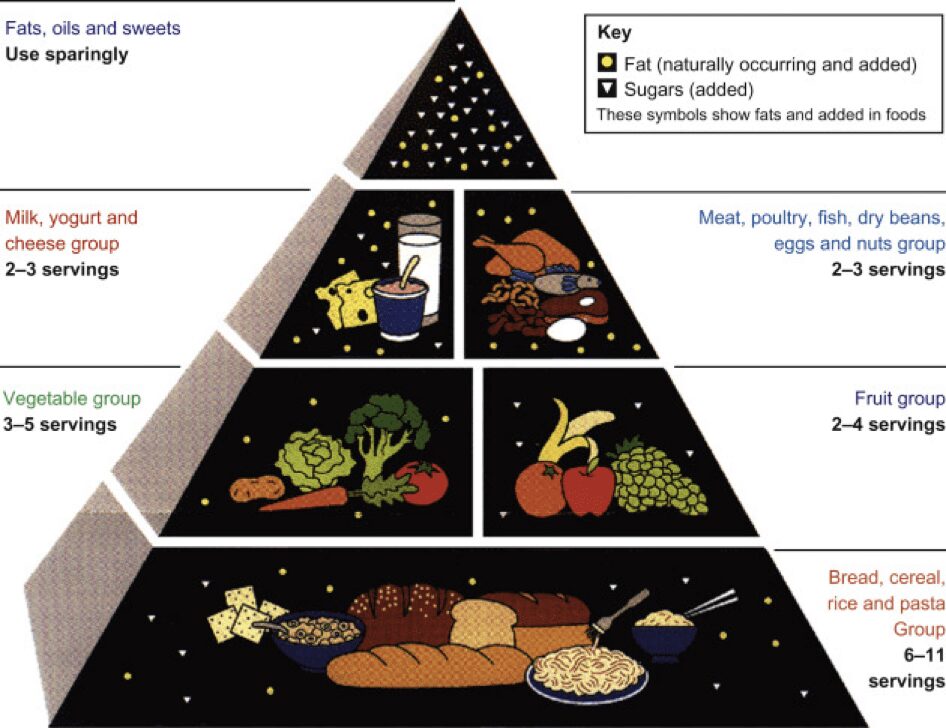

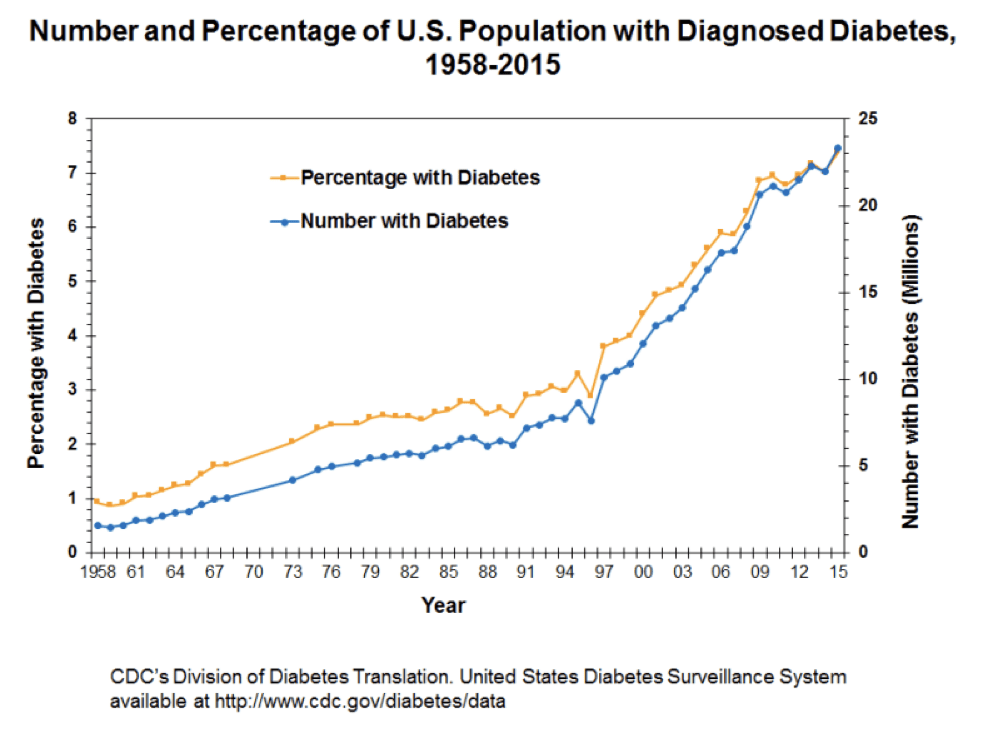

By the end of the 1970s, the U.S. government and most of its international vassals were recommending the modern food pyramid. The fiat subsidized grains of the agricultural industrial complex feature heavily in this pyramid, which advertises them as the base of the diet, recommending six to eleven servings a day. This food pyramid is a recipe for metabolic disease, obesity, diabetes, and a plethora of health problems that have become increasingly common in the intervening decades, to the point most people think of them as a normal part of life. The next section will focus on listing the most damaging industrial substances that have been marketed as food by the fiat system, while the next chapter examines the scientific process behind it.

3. Fiat foods

1. Polyunsaturated and hydrogenated “vegetable” and seed oils

A century ago, the majority of fats humans consumed consisted of healthy animal fats like butter, ghee, tallow, lard, and schmaltz. Today, most fat consumption comes in the form of toxic, heavily processed industrial chemicals misleadingly referred to as “vegetable oils.” These are mainly soy, rapeseed, sunflower, and corn, as well as the abomination that is margarine. The diet change that would likely cause the largest improvement in a person’s health with the least effort is the substitution of these horrific industrial chemicals for healthy animal fats.

Most of these chemicals did not exist one hundred years ago, and those that did were mainly deployed in industrial uses, such as lubricants. As industrialization spread and the government stoked hysteria against animal fats, these toxic chemicals have been promoted worldwide by governments, doctors, nutritionists, and their corporate sponsors as the healthy alternative. The spread of this sludge across the world, replacing all the traditional fats used for millennia, is an astounding testament to the power of government propaganda hiding under the veneer of science. The late Dr. Mary Enig of the Weston Price Foundation had spent her life warning of the dangers of these chemicals, with very little attention. Here she lists the different kinds of fat available, while here she discusses their impact on health.

2. Processed corn

In the 1970s, government policy pushed the mass production of corn and used policies to make its price very cheap. As a result, American farmers had a large surplus of corn crops. This abundance of cheap corn led to the development of many creative ways to use it in order to benefit from its low price. The overproduction of corn has become so excessive that the cheap inferior products of the corn plant are now used where other substances would be a far better, healthier, or more efficient option. Sweeteners, gasoline, cow feed, and countless industrial processes all deploy heavily subsidized corn for its cheapness, when far superior alternatives exist.

One of the most destructive uses of corn is the production of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which has replaced sugar as a sweetener in the U.S. because it is so cheap, and because tariffs on sugar in the U.S. make sugar very expensive. In 1983 the FDA blessed this new substance with the classification of “Generally Recognized as Safe,” and the floodgates opened in an unbelievable manner. Since then, American candy, industrial food, and soft drinks have become almost universally full of HFCS, which is arguably even more harmful than regular sugar, on top of being nowhere near as appetizing or desirable. If you have ever wondered why candy and soft drinks taste much better everywhere other than in the U.S., now you know why: the rest of the world uses sugar while the U.S. uses its digestive systems and cars to consume the corn that is depleting its soil, degrading its engines, and destroying the health of its people with obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, liver damage, and much more.

3. Soy

Historically, soy was not an edible crop, used instead to fix nitrogen in the soil. The Chinese first figured out how to make it edible through extensive fermenting in products like tempeh, natto, and soy sauce. Famines and poverty later forced oriental populations to eat more of it, and it has arguably had a negative effect on the physical development of the populations that have depended on it for long.

Modern day soy products come from Soybean lecithin. The squeamish may want to skip this, but here is how the Weston Price Foundation described the process by which this abomination is prepared:

Soybean lecithin comes from sludge left after crude soy oil goes through a “degumming” process. It is a waste product containing solvents and pesticides and has a consistency ranging from a gummy fluid to a plastic solid. Before being bleached to a more appealing light yellow, the color of lecithin ranges from a dirty tan to reddish brown. The hexane extraction process commonly used in soybean oil manufacture today yields less lecithin than the older ethanol-benzol process, but produces a more marketable lecithin with better color, reduced odor and less bitter flavor.

Historian William Shurtleff reports that the expansion of the soybean crushing and soy oil refining industries in Europe after 1908 led to a problem disposing the increasing amounts of fermenting, foul-smelling sludge. German companies then decided to vacuum dry the sludge, patent the process and sell it as “soybean lecithin.” Scientists hired to find some use for the substance cooked up more than a thousand new uses by 1939.

While there are many great uses for soy in industry, its use as food has largely been an unmitigated disaster, as the above article makes clear. But the overwhelming evidence attesting to the destructive nature of soy foods is no match for the motivated reasoning of special interest groups that have effectively captured government regulators. Government-approved dietary guidelines continue to push such toxic plant matter as a substitute for meat.

4. Low fat foods

The insane notion that animal fats are harmful has spurred the creation of many substitutes for fatty foods that contain low or no fat. Without delicious animal fat, these products all become tasteless and unpalatable. Food producers quickly discovered that the best way to make them palatable was to introduce sugars. Those who try to avoid animal fat because of dietary guidelines will find themselves hungry more often. They need to binge on endless doses of sugary snacks all day, junk food that contains lots of chemicals and artificial, barely edible (or pronounceable) compounds. As the consumption of animal fat declined, the consumption of sweeteners, particularly HFCS, increased as a flavor substitute. But the addictive nature of these substitutes means that people deprived of wholesome, satiating animal fats end up being constantly hungry and are more likely to resort to eating large quantities of the cheap industrial alternatives.

The popularization of fat-free skim milk has been one of the most destructive battles in the crusade against saturated fats. In the early twentieth century, American farmers used the leftovers from the production of butter to fatten their pigs, as combining it with corn provided the quickest way to fatten a hog. Through the magic of the fiat scientific method, corn with skimmed milk ended up being the human breakfast recommended, promoted and subsidized by fiat authorities, with the same fattening result.

John Kellogg, another devout Seventh-day Adventist and a follower of Ellen White, viewed sex and masturbation as sinful, and his idea of a healthy diet was one that would stifle the human sex drive. He was correct and astoundingly successful in marketing his favorite breakfast to billions worldwide.

5. Refined flour and sugar

Whole grain flour and natural sugars have been consumed for thousands of years. Whole grain flour, produced from the whole grain, contains the germ and bran, which contain all the nutrients in the wheat. As Weston Price documented, elaborate rituals existed for preparing whole wheat, and it was eaten with ample animal fat. Industrialization changed things drastically for these two substances, effectively turning them into highly addictive drugs.

Goldkeim, producers of whole flour, explain:

An important problem of the industrial revolution was the preservation of flour. Transportation distances and a relatively slow distribution system collided with natural shelf life. The reason for the limited shelf life is the fatty acids of the germ, which react from the moment they are exposed to oxygen. This occurs when grain is milled; the fatty acids oxidize and flour starts to become rancid. Depending on climate and grain quality, this process takes six to nine months. In the late 19th century, this process was too short for an industrial production and distribution cycle. As vitamins, micronutrients and amino acids were completely or relatively unknown in the late 19th century, removing the germ was an effective solution. Without the germ, flour cannot become rancid. Degermed flour became standard. Degermation started in densely populated areas and took approximately one generation to reach the countryside. Heat-processed flour is flour where the germ is first separated from the endosperm and bran, then processed with steam, dry heat or microwave and blended into flour again.

In other words, industrialization solved the problem of flour perishing and ruining by industrially removing the nutrients from it.

Sugar, on the other hand, had existed naturally in many foods, but in its pure form was rare and expensive, since its processing required large amounts of energy, and its production was almost universally done by slaves, because few would choose to work that exhausting job of their own volition. As industrialization and capital accumulation allowed for the replacement of slave labor with heavy machinery, people were able to produce sugar in a pure white form, free of all the molasses and nutrients that accompany it, and at a much lower cost.

Refined sugar and flour can be better understood as drugs, not food. Sugar contains no essential nutrients, and flour only contains very little. The pleasure that people get from consuming them is the pleasure you get from a hit of an addictive substance; they do not offer nutrition to the body. In Bright Line Eating, Susan Thompson explains how the refining of sugar and flour is similar to the refining process that has made cocaine and heroin such highly addictive substances. Whereas chewing on coca leaves or eating poppy plants will give someone a high and an energy kick, it is nowhere near as addictive as consuming purified cocaine or heroin. Many cultures consumed these plants for thousands of years with adverse effects far less severe than the damage their refined and processed descendants do to their modern consumers. The industrial processing of these plants into their modern, highly potent drug form has made them extremely addictive. It allows those consuming them to ingest large quantities of the pure essence of the plant without any of the rest of the plant matter that comes with it. The high is intensified, as is the withdrawal that follows it and the craving for more. Thompson makes a compelling case that the processing of these drugs is very similar to the processing of sugar and flour in how addictive it makes them, citing studies that show sugar is eight times more addictive than cocaine.

4. The Harvest of Fiat

Seed oils and soy products have legitimate industrial uses, corn, soy, and low-fat milk are passable cattle feed, though not as good as letting cattle graze. Processed flour and sugar can be used as recreational drugs in tiny quantities, but none of these products have a place in a human diet, and must be avoided for a human to thrive and be healthy. Yet as technology and science continue to advance and make them cheaper, and government subsidies to them increase, we find people consuming ever-increasing barely believable quantities of them. Faster and more powerful machines can reduce the cost of producing these materials very significantly, and as industrial technology has advanced producing these foods has become less and less expensive.

Industrialization can do little to improve the cost of producing nutritious red meat which needs to grow by walking on large areas of land, grazing, and getting sun, and which also perishes quickly. But the fiat foods of mono-crop agriculture have a stable shelf-life allowing them to remain on in storage and display for years, allowing them to spread far and wide. Worse, their shelf-stability allows them to be manufactured into highly-processed foods that are engineered to be highly palatable and addictive. The universal ubiquity of these cheap, heavily-subsidized, highly-palatable and toxic foods has been an unmitigated disaster for the health of the human race.

Another way of understanding the impact of rising time preference is in the decision-making of individuals when it comes to food choices. As depreciating money drives people to prioritize the present, they are more likely to indulge in foods that feel good in the moment at the expense of their future health. The shift toward short-term orientation in decision-making would invariably favor more consumption of the junk foods mentioned above. Modern fiat medicine is highly unlikely to mention the obvious dietary drivers of modern diseases, as prevention makes for bad business. While the prevalent religious faith in the power of modern medicine to correct all health problems further encourages individuals to believe industrial waste has no consequences.

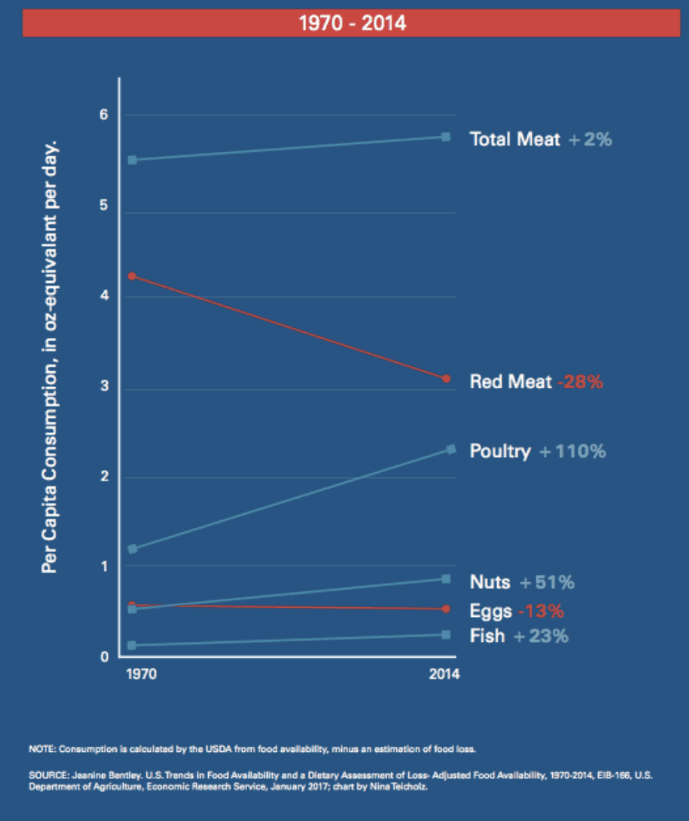

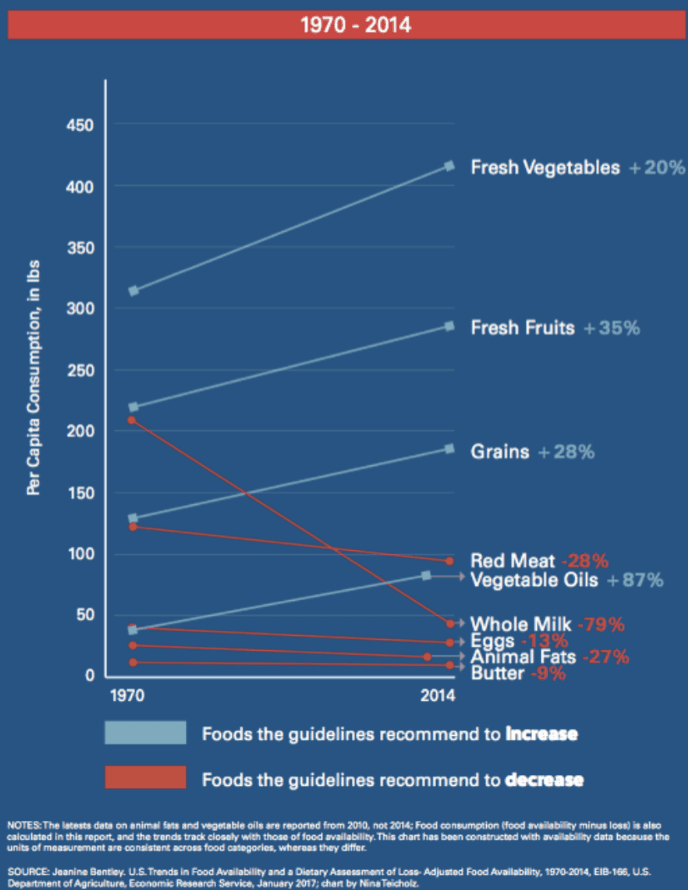

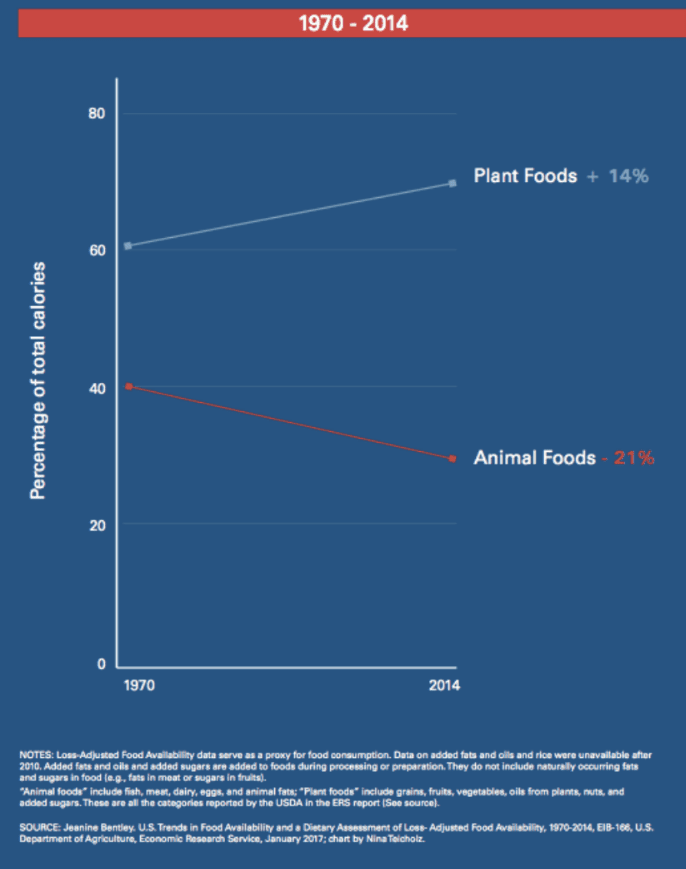

Government subsidies for the production of unhealthy foods—and government scientists recommending and requiring we eat them—have been extremely effective in altering Americans’ food choices. In the years between 1970 and 2014, Americans’ per capita consumption of red meat declined by 28%, whole milk by 79%, eggs by 13%, animal fats by 27%, and butter by 9%. By contrast, the consumption of toxic “vegetable” oils increased by 87%, and grains increased by 28%. In a show of exemplary compliance with government guidelines, Americans have also increased their consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables significantly, which is an important indicator that the driver of obesity is not the absence of vegetables and fruits, but the decline in meat consumption, particularly red meat. Overall meat consumption stayed relatively constant, rising by 2%, but that happened because American meat-eaters began substituting inferior, cheap, mass-produced poultry for highly nutritious essential red meat. Overall, Americans’ calories from animal foods declined by 21%, while calories from plant foods increased by 14%. Nina Teicholz estimates the average American ate around 175 pounds of meat per year in the nineteenth century, predominantly from highly nutritious red meat. Today, the average American eats around 100 pounds of meat per year, but half of that comes from poultry. A century of technological progress and ever-increasing economic growth has somehow not translated to an increase in the consumption of the most sought-after and nutritious food. Instead, Americans are increasingly having to make do with inferior and cheaper sources of food.

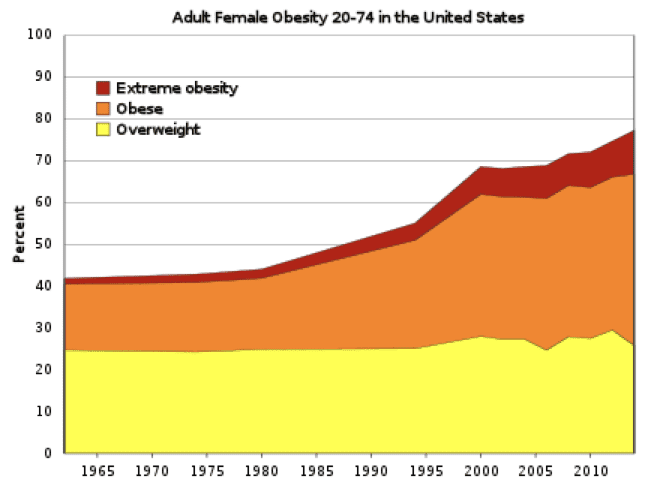

The impacts of this dietary transition on Americans’ health have been calamitous. Obesity has been increasing steadily since the 1970s, along with many chronic diseases which modern nutrition science and its corporate sponsors has done everything to pretend are unrelated to diet.

One cannot find a more apt representation of the impact of inflation and unsound money: the paper wealth of Americans is increasing, while the statistics show that their quality of life is rising. In reality however, the quality of their food is degrading because the quantity of nutrients they consume is declining, and their mental and physical health are deteriorating. Instead of nutrients, Americans are increasingly subsisting on drugs and toxic industrial products. The ever-growing variety and quantities of flavored industrial sludge filling Americans’ refrigerators is not food, nor is it a satisfactory substitute. Americans’ increasing obesity is not a sign of affluence but a symptom of deprivation. The level of spending and income in America may be increasing according to government statistics, but if Americans work longer hours than they ever did and their basic nutrition is deteriorating, there must be something seriously wrong with the money they are using, both as a store and measure of value. The Faustian bargain of fiat money did not deliver the free lunch its cheerleaders promised. Instead, it brought industrial concoctions of soy sludge and high fructose corn syrup, light on nutrients, high on empty calories, and extremely costly to the health and well-being of its consumers. The ever-increasing cost of medication and healthcare cannot be understood without reference to the deterioration of health, diet, and soil, and the economic and nutritional system that promoted this calamity.

The modern world suffers from a crisis of obesity unprecedented in human history. Never before have so many people been so overweight. Modernity’s tragically self-flattering misunderstanding of this crisis is to cast it as a crisis of abundance: it is the result of our affluence that our biggest problem is obesity rather than starvation. The flawed paradigm of nutrition—another field of academic inquiry thoroughly disfigured by government funding and intervention—emphasizes the importance of obtaining a necessary quantity of calories, and that the best way to secure the needed calories is by eating a diverse and “balanced” diet that includes hefty portions of grains. Animal meat and fat are viewed as harmful, best consumed in moderation, if at all.

From this perspective, obesity occurs when too many calories are consumed, and malnourishment occurs when too few calories are consumed. This view is as overly simplistic and ridiculous as Keynesian textbooks’ insistence that the state of the economy is primarily determined by the level of aggregate spending, with too much spending causing inflation, and too little spending causing unemployment. In reality, nutrition is about far more than caloric intake. It is about securing sufficient quantities of essential nutrients for the body, which come in four categories: proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals. The fats are primarily used to provide the body’s energy, the proteins for building and rebuilding the body and its tissues, and the vitamins and minerals are necessary for vital processes that take place in the body. The other major food group, carbohydrates, is not essential to the human body but can be utilized to provide energy. In the absence of essential nutrients, the body begins to deteriorate, with negative consequences manifesting as diseases. In particular, the absence of animal proteins and fatty acids cause the body to enter starvation mode: energy expenditure is reduced, manifesting in physical and mental lethargy, and the body begins to convert its intake of carbohydrates into fatty acid deposits for storage for future use (in other words, fat). Rather than a sign of affluence and overfeeding, obesity is actually a sign of malnutrition. The ability to digest sugars and convert them into stores of fatty acids is an extremely useful evolutionary strategy for dealing with hunger in the short run, but when the deprivation of essential nutrients becomes a lifestyle, the fat storage turns into the debilitating sickness of obesity. Americans are not fat because of prosperity and abundance; Americans are fat because they are malnourished and nutritionally impoverished.

5. Sound Food

The state of nutrition research is analogous to the state of economic research: a fiat-financed mainstream heavily invested in arriving at the conclusions conducive to its fiat financing. Economics has its Austrian alternatives such as Mises, and nutrition has some equivalents. As the field has descended to the status of marketing of junk food, as will be discussed in the next chapter, some renegades have for long attempted to counter the prevailing narrative. John Yudkin’s heroic but doomed struggle against sugar is particularly noteworthy. But perhaps the most comprehensive framework for studying nutrition comes from the work of Weston Price, a Canadian dentist working a century ago.

Price is mainly known today as both a dentist and a pioneer in the discovery and analysis of several vitamins, but his magnum opus, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration is largely ignored by the mainstream of academia and nutrition science, as his conclusions fly against the politically correct dogma taught in medical and nutrition schools in modern universities. Price provides a rigorous and clean exploration of the horrible damages caused by modern industrial foods whose producers are the main benefactors of nutrition schools everywhere today. On top of being methodologically thorough and well-documented, Price’s research is unique, and likely impossible to repeat. He spent many years traveling the world just as airplanes were invented and closely observed the diet and health of people from cultures across all continents, meticulously documenting their diets and their overall health, particularly their dental health. Since flight was so novel, he was able to visit many areas which were still largely isolated from world markets and thus reliant on their own local traditionally-prepared food items. All of these places have been far better integrated into global trade and their diets are quickly degenerating into the appropriately acronymed SAD-Standard American Diet. Price took thousands of pictures of the people he studied as well as countless samples of their foods, which he then sent to his laboratories in Ohio for analysis.

Across the world, Price compared the diets of genetically similar separate populations. The major difference between the populations he compared was that, in each comparison, one population was integrated into global trade markets with access to industrial foods, while the other was isolated and eating its local, traditionally prepared foods. Price studied Inuits in northern Canada and Alaska, Swiss villagers in isolated valleys, herdsmen in central Africa, Pacific Islanders, Scottish farmers, and many other populations. No matter where in the world you come from, Price visited your ancestors or people not too far from them. The results were as stark as they are edifying, and Price arrived at several important conclusions. While it is really impossible to do justice to this momentous work in a few paragraphs, there are some important conclusions worth discussing.

One of the purposes of Price’s trip was to find “native dietaries consisting entirely of plant foods which were competent for providing all the factors needed for complete and normal physical development without the use of any animal tissues or product.” But after scouring the globe, Price did not find a single culture that subsisted on plant foods exclusively. All healthy traditional populations relied heavily on animal products. The healthiest and strongest populations he found were the Inuit of the Arctic and African herders. Almost nothing about the environment and customs of those two populations is similar in any way, except for the fact that they both relied almost exclusively on animal foods. Price came to see the sacred importance of animal fats across all societies, and analyzed the lengths to which populations went to secure it. Price found many nutrients that cannot be obtained from plants, and conclusively demonstrated that it is simply not possible to be healthy for any significant period of time without ingesting animal foods. To the extent that plant food was eaten, its role seemed primarily to be a vessel for ingesting precious fats.

Since Price’s research, nobody has managed to produce evidence of a single indigenous human society anywhere whose diet excludes animal foods. All human societies, from the arctic to the tropics, on every continent, throughout history have based their diet around animal foods. The internet has allowed dietary knowledge to escape the grip of fiat science, and so more humans have learned about Price’s work. Countless other scholars, doctors, dietitians, and physical trainers have also become willing to counter the fiat dogma.

Thanks to the spread of dietary knowledge outside of the politically correct, government-sanctioned channels, we are beginning to see a very clear pattern emerge from people who shift their diet from one based on fiat garbage to one based predominantly on animal foods: a huge reduction in their desire for junk and ultra processed food. The need to constantly be eating junk food is not just a product of its engineered hyper palatability and addictive properties. Junk food cravings are also a result of deep malnutrition caused by not eating enough meat. No wonder the antimeat message is blared out relentlessly by mainstream media, academia, and other industrial food marketing outlets. The less meat people eat, the more highly profitable, subsidized junk they must replace it with. One can only imagine how different modern nutrition science would be if its purpose was to inform humans of how to be healthy rather than manipulate them into eating poisons for the profit of food corporations.

Another important conclusion from Price’s work is that the diseases of civilization that we’ve accepted as a normal part of life largely began to appear with the introduction of modern processed foods, in particular, grains, flours, and sugars. The book is full of stories and analysis that make this an inescapable conclusion. Here is but one of many examples to illustrate the point, drawn from Chapter 21:

“The responsibility of our modern processed foods of commerce as contributing factors in the cause of tooth decay is strikingly demonstrated by the rapid development of tooth decay among the growing children on the Pacific Islands during the time trader ships made calls for dried copra when its price was high for several months. This was paid for in 90 per cent white flour and refined sugar and not over 10 per cent in cloth and clothing. When the price of copra reduced from $400 a ton to $4 a ton, the trader ships stopped calling and tooth decay stopped when the people went back to their native diet. I saw many such individuals with teeth with open cavities in which the tooth decay had ceased to be active.”

Price closely studied how various cultures prepared their plant foods and extensively documented the methods needed to make most grains and plants palatable and nontoxic. These heavily complex traditional rituals of soaking, sprouting, and fermenting are necessary to remove the many natural toxins that exist in plant foods, and they allow the body to absorb the nutrients in these foods. In the high time preference age of fiat, nobody has time for these rituals, and instead, the majority prefer the industrial food-processing methods which rely on maximizing the sugar and palatable ingredients at the expense of nutrients. Price contributed massively to our understanding of nutrition and health, but like Menger and Mises in economics, his teachings are largely ignored by the paper-pushing, government-employed bureaucrats pretending to be scientists. Not coincidentally, listening to these government employees and ignoring Price has come at a devastating cost not just to the health of individuals but also in bloated healthcare spending, which has saddled productive with onerous tax burdens. With a better understanding of nutritional science, resources currently dedicated to diabetes and other obesity-related diseases could instead be applied to more productive endeavors. Price’s research shows that the trends most responsible for malnutrition, obesity, and some diseases of modern civilization are directly related to the economic realities of the twentieth century. The nutritional decline Price documented happened around the turn of the twentieth century, which, coincidentally, was when the modern world economy moved away from the hard money of the gold standard and toward easy government money.

It in unquestionable that a large part of the problem of modern industrial diets lies in the availability of modern high powered machinery capable of efficiently and quickly processing plants into hyperpalatable junk food. Yet, given everything discussed above, it is very difficult to argue that the fiat money experiment of the last century has not massively exacerbated the impact of modern industrial foods by heavily subsidizing them, and subsidizing the miseducation of generations of nutritionists and doctors who promote them. On a hard money standard, we would still have these industrial foods. But without fiat subsidies, they would not have been so ubiquitous in modern diets. Fiat has facilitated the growth of the managerial state and the production of mass propaganda “research.” Fiat has given us unscientific dietary guidelines tailored to normalize the consumption of industrialized food sludge. Fiat has paid credentialed types in white coats to warn against the dangers of healthy, wholesome, nonindustrial (but low profit-margin) foods, like meat. In the absence of this fiat-driven dynamic, most people’s understanding of nutrition would be very different and far more similar to the traditions of their ancestors, which revolved heavily around animal foods.

6. Fiat soils

The heavily discounted future that the fiat system incentivizes, discussed in the previous chapter, is not only reflected in the increased indebtedness of capital markets, but also anywhere people can trade off the future for the present, most notably the natural environment and the soil. As individuals’ time preference rises and they start to discount the future more heavily, they are less likely to value the maintenance of a healthy future state for their natural environment and soil. Consider the effect this would have on farmers: the higher a farmer’s time preference, the more they will discount the future health of their soil, and the more likely they are to care about maximizing their short-term profits. Indeed, this is exactly what we find with soil depletion leading up to the 1930s, the time of Price’s writing. The introduction of modern industrial production methods, thanks to the utilization of hydrocarbon energy, has allowed humans to increase the intensity with which they utilize land, and consequently the number of crops they grow on a given patch of soil. The story of increasing agricultural productivity is often touted as one of the great successes of the modern world, but the heavy cost it has imposed on the soil goes largely unmentioned. It is very difficult to grow plants on most agricultural topsoil in the world today without the addition of artificial, industrially produced chemical fertilizers. The nutritional content of the food grown on such soil is steadily degrading compared to food grown on rich soil.

Price’s study begins with a discussion of the quality of soil in modern societies, which he found was quickly degrading. The degradation of farmland, Price found, was causing severe nutrient deficiencies in food. Price published his book in the 1930s, and he had pinpointed the few decades prior as a time of particular decline in the nutrient content of land. While he does not explicitly draw a connection with fiat money, the development is perfectly consistent with the analysis of fiat and time preference discussed in Chapters 5 and 7. Soil, being the productive asset from which all food comes, is capital. And as fiat encourages the consumption of capital, it will encourage the consumption of soil. We can understand the drive of industrial agriculture as the high time preference stripping of productive capital from the environment.

Heavily-plowed industrial agriculture is an object lesson in high time preference, as is well understood by farmers worldwide, and well-articulated in the website of the Natural Resource Conservation Service of the US Department of Agriculture:

The plow is a potent tool of agriculture for the same reason that it has degraded productivity. Plowing turns over soil, mixes it with air, and stimulates the decomposition of organic matter. The rapid decomposition of organic matter releases a flush of nutrients that stimulates crop growth. But over time, plowing diminishes the supply of soil organic matter and associated soil properties, including water holding capacity, nutrient holding capacity, mellow tilth, resistance to erosion, and a diverse biological community.

The work of Alan Savory on the topic of soil depletion is very important here. The Savory Institute has been working on reforestation and soil regeneration across the world with spectacular success. Their secret? Unleashing large numbers of grazing animals on depleted soil to graze on whatever shrubs they can find, till the land with their hooves, and fertilize it with their manure. The results, visible on their website, speak for themselves and clearly illustrate a strong case for keeping soil healthy by holistically managing the grazing of large mammals on it. Agricultural crop production, on the other hand, quickly depletes the soil of its vital nutrients, making it fallow and requiring extensive fertilizer input to be productive. This explains why pre-industrial societies worldwide usually rotated their land from farming to grazing. After a few years of farming a plot whose output had begun to decline, the land was abandoned to grazing animals, and farmers moved to another plot. After that one was exhausted, farmers moved on to another plot, or returned to the earlier one if it had recovered. Cattle grazing increases the soil’s ability to absorb rainwater, allowing it to become rich with organic matter. After a few years of grazing, the land becomes ready once again for crop farming.

The implication here is very clear: low time preference approaches to managing land would prioritize the long-term health of the soil, and thus entail the management of cropping along with the grazing of animals. A high time preference approach, on the other hand, would prioritize an immediate gain and exploit the soil to its fullest with little regard for long-term consequences. The mass production of crops, and their increased availability in our diet in the twentieth century, can also be seen as a consequence of rising time preference. The low time preference approach involves the production of a lot of meat, which usually has small profit margins, while the high time preference approach would favor the mass production of plant crops, which can be optimized and scaled drastically with the introduction of industrial methods, allowing for significant profit margins.

As industrialization introduced heavy machinery to plow the soil, and as fiat money discounted the utility of the future, the traditional balance between crop farming and grazing was destroyed and replaced with intensive agriculture that depletes the soil very quickly. Rather than regenerate the soil naturally with cattle manure, industrial fertilizers are applied in ever-increasing amounts, often with devastating unintended consequences. For example, the impact of industrial fertilizer runoff in the Mississippi River Delta and the Gulf of Mexico is well documented. Industrial food conglomerates chasing quick profits saturate the land with chemical fertilizers, which in turn enter the Mississippi River and kill fish, cause algae blooms, and even

make the water unfit for human consumption.

Industrial farming allows farmers to strip nutrients from their soil rapidly, maximizing output in the first few years, at the expense of the long-term health of the soil. Fertilizers allow this present orientation to appear relatively costless in the future, since depleted soil can still be made fertile with industrial fertilizers. After a century of industrial farming, it is clear that this trade-off was very costly, as the human toll of industrial farming grows larger and clearer. By contrast, maintaining healthy soil through rotating cattle grazing and crop farming will offer less reward in the short run, but it will maintain the health of the soil in the long run. A heavily plowed field producing heavily subsidized fiat foods would allow the farmer a large short-term profit, while careful management of the soil would allow the farmer a more sustainable income into the future. Just because industrialization allows for the quick depletion of the soil, it does not mean that people are obliged to engage in it any more than access to cliffs should compel people to jump off them. Understanding the distortions of fiat and high time preference helps us understand why this style of agriculture has become so popular in spite of its massively detrimental effect on humans and their soil.

It is remarkable to find that within the field of nutrition, and without any reference to economic or monetary policy, Price had identified the first third of the twentieth century as having witnessed immense soil degradation and a decline in the richness of nutrients in the food that farms produced. The great cultural critic Jacques Barzun, in his seminal history of the West, From Dawn to Decadence, precisely identified 1914 as the year in which the decline of Western civilization began, when art began its shift toward the less sophisticated modern forms, and when political and social cultures shifted from liberalism to liberality. Like Price, Barzun made no mention of the shift in monetary standards and the link it might have to the degradation he identified. In the work of these two great scholars, prime experts in their respective fields, we find compelling evidence of a shift toward more present-orientated behavior across the Western world in the early twentieth century. As with his architecture, art, and family, fiat man’s food quality is constantly declining, as well-marketed, addictive, and toxic fiat “food” replaces the healthy, nourishing, traditional foods of his ancestors. The soil from which life and civilization spring continues to get depleted, and its essential nutrients are replaced by petroleum-derived chemical fertilizers marketed as soil by fiat.