Table of Contents

Between 1914 and 1971, the global monetary system gradually and haphazardly moved from the gold standard to the fiat standard. Governments effectively took over the banking sector everywhere, or depending on who you ask, the banking sector took over governments. Details of who wore the pants in this relationship are of no concern to this book, which focuses on its bastard spawn. Like The Bitcoin Standard, this book is focused on exploring the characteristics of its subject monetary system as demonstrated in practice, eschewing a detailed historical account of its development.

Fiat can be defined as a compulsory implementation of debt-based, centralized ledger technology monopolizing financial and monetary services worldwide. The fiat standard was born out of the need for governments to manage their de facto default on their gold obligations. It was not designed to optimize the user experience of currency, transactions, and banking. With this in mind, this chapter takes a closer look under the hood of the monetary technology powering most of the world’s trade today. Contrary to what the name suggests, modern fiat money is not conjured out of thin air through government fiat. Governments do not just print currencies and hand them out to societies that accept them as good money. Modern fiat money is far more sophisticated and convoluted in its operation. The fundamental engineering feature of the fiat system is that it treats future promises of payment of money as if they were as good as present money, so long as they are issued by the government, or an entity guaranteed a lending license by the government.

In the bitcoin network, only coins that have already been mined can settle transactions. In a gold-based economy, only existing gold coins or bars can be used to settle transactions and extinguish debt. In both cases it is possible for a seller or lender to hand over their present goods in exchange for a promise of future bitcoin or gold, but they take on risk personally, and if the buyer or lender fails to provide the coins on time, they are lost to the lender, who would learn a valuable lesson about being more careful with lending. With fiat, government credit allows nonexistent tokens from the future to be brought to life to settle transactions in the present when a loan is made, allowing the borrower and lender to have a larger amount of fiat tokens between them than when they started, thus devaluing the rest of the network’s tokens. The fiat network creates more tokens every time a government-licensed entity makes a loan in the local fiat token.

Having been born out of government default, the essential characteristic of the fiat standard is that it uses government decree as the token of value on its monetary and payment network. Since the government can decree value on the network, it effectively makes its own credit money. As the government backs the entire banking system, this makes all credit issued by the banking system effectively the government’s credit, and so part of the money supply. In other words, the U.S. Congress and Federal Reserve are not the only institutions capable of conjuring money from thin air; any lending organization also has the capacity to increase the money supply through lending.

Blurring the line between money and credit makes measuring the money supply practically impossible. In a payment system like gold or bitcoin, only mature money (or money of full maturity, meaning money that does not have a future period of maturity at which it acquires its full liquid value) can be used to settle payments and debts. Under a fiat system, money that has not matured, and will only do so in the future, can be accepted as payment, so long as it is guaranteed by a commercial entity with a lending license.

Unlike with a pure gold standard or with bitcoin, the supply is not a set objective number of units being traded between network members. The units are ephemeral, constantly being created and destroyed. Their quantity is dependent on a subjective choice of which imperfect definition of money one uses. This makes it virtually impossible to obtain an objective, agreed-upon measure of the supply of money, or to audit the supply, as is the case with bitcoin.

When a client takes out a $1 million loan to buy a house, the lending bank does not take a preexisting mature $1 million present in its cash reserves, or from a depositor’s balance at the bank. It will simply issue the loan and create the dollars that are used to pay the seller of the house. These dollars did not exist before the loan was issued. Their existence is predicated on the borrower fulfilling their end of the bargain and making regular payments in the future.

No present goods are used in the home purchase; no saver had to set the tokens aside to give to the borrower to pay the house seller. The present good of the house is handed to the borrower without them having to offer a present good in exchange, and the house seller does not grant the credit to the borrower nor take on the risk of default. The bank grants the credit, and the credit risk is ultimately borne by the central bank guaranteeing the bank, the loan, and the currency. Had the house seller granted the credit, they would be taking on the risk of default and giving up their present good willingly, affecting no other parties. But by utilizing the fiat standard, the house seller receives their payment in full up front, and the buyer receives the house in full up front. Both parties walk away with present goods they can use in full, even though only one of these goods existed before the transaction took place. The new fiat tokens created to allow this transaction place the risk of the buyer defaulting on all holders of the currency.

All three parties involved in the house transaction are happy, but could such a system survive in a free market? It appears favorable to the buyer, who can buy a home without having to pay the full price up front. It appears favorable to the seller because it finances more potential buyers and bids up the price of their home. It also appears favorable to the bank, which can mine new fiat tokens at roughly zero marginal cost every time a new lender wants to buy a house. However, the transaction only works by externalizing the risk to society at large, protecting the buyer, seller, and bank from default by having the government’s currency holders effectively absorb the risk premium through the inflation of the money supply. The sacrifice of the present good that allows both to spend can only come at the expense of the currency being devalued.

Should a fiat system coexist with a hard money system in a free market, one would expect the rational investor to prefer to hold their wealth in the harder money, which cannot be debased to finance credit. However, even without the rational self-interest of the investor, inflation causes a currency to lose value over time next to the harder currency. This means that it is inevitable, in the long term, that most economic value will accrue to the harder currency. But by monopolizing the payment networks necessary for the modern division of labor, governments can make currency holders take that risk for significant periods.

To create an analogy with bitcoin’s operation, we could say that the fiat network creates or destroys a number of new tokens with each block, equal to the amount of lending that has taken place minus the amount of credit repaid and defaulted on. Rather than a set new number of coins to be added with each block, as with bitcoin’s protocol, the number of fiat tokens added in each fiat time period is the net result of debt creation, which can vary widely and can be positive or negative.

Network Topography

The fiat network is composed of around 190 central bank members of the International Monetary Fund, as well as tens of thousands of private banks, with many physical branches. At the time of writing, the fiat network has achieved almost universal adoption, and almost everyone on earth is either dealing with a fiat node, or handling fiat paper notes issued by such nodes. The Fiat Network is not voluntary and not optional; it can be best likened to mandatory malware. With the exception of a few primitive and isolated tribes yet to have fiat enforced upon them, every human on earth is assigned to a regional node where he or she must pay his or her taxes in their local fiatcoin. Failure to pay with the local fiatcoin can result in physical arrest, imprisonment, and even murder. This is an important driver for adoption which Bitcoin and gold lack.

The fiat network is based on a layered settlement system for payment clearance. Individual banks handle transfers between their clients on their own balance sheets. National central banks oversee clearance and settlement between banks in their jurisdiction. Central banks, and a few hundred international correspondence banks oversee clearance across international borders on the SWIFT payments network. The Fiat Network utilizes a highly-efficient centralized ledger technology with only one full node required to validate and decide the full record of transactions and balances. The entity is the United States Federal Reserve, under the influence and supervision of the United States Government. “The Fed,” as it is known to fiat enthusiasts, is the focal and central point of the fiat network topology. It is the only entity that can invalidate any transaction and confiscate any balance from any other fiat node. The Fed controls the SWIFT payment network and can prevent entire nations from joining this payments system and settling trades with other nations.

The fiat network’s base layer operates using a native token of debt denominated in United States Dollars. While it is common for fiat enthusiasts to think and talk of the network as having a variety of tokens, each belonging to a different country or region, the reality is that all secondary layer tokens are merely derivatives of the US dollar whose value depends on their backing in the US Dollar, and can best be approximated as the value of the US dollar with a discount equivalent to the country risk. For a variety of historical, monetary, fiscal, and geopolitical reasons, it has not been possible for any of the tokens to appreciate significantly against the US dollar in the long term. For all practical intents and purposes, national central banks managing their currency can either maintain its exchange rate with the dollar, or devalue it faster than the dollar.

Financial institutions mine the network’s native token—fiatcoin—through the arcane, centralized, manual, risky, and haphazard process of lending. A complex web of government rules and regulations determines how an institution can obtain the lending license that allows it to issue loans. These rules and regulations are typically promulgated by central governments, central banks, the Bank for International Settlements, or the IMF. Unlike with bitcoin, there is no easily verifiable proof-of-work protocol and no algorithmic adjustment to ensure the fiatcoin supply remains within known and clearly auditable parameters.

As a centrally planned system, the fiat standard does not allow for the emergence of a free market in capital and money where supply and demand determine the interest rate, i.e., the price of capital. Lending ultimately determines the money supply, and lending levels are in turn shaped by the interest rate and Federal Reserve policy. The Federal Reserve’s full fiat node holds periodic meetings for its central planning committee to decide the optimal interest rate to charge other nodes. The rate these unelected bureaucrats set is known as the federal funds rate, and all other interest rates are derived from this and rise as they get further away from the central node. The closer the borrower is to the Federal Reserve System, the lower the interest rate they can secure and the more likely they are to benefit from inflation of the money supply.

While a small percentage of fiatcoin is printed into paper bearer instruments with local insignia, the vast majority is digital, stored on the central node’s ledger or the ledgers of the peripheral nodes. The digital fiat network offers limited possibility for final settlement, as all balances are tentative at all times, and partial nodes, or the full node itself, can revoke or confiscate any balance on any ledger at any time. Withdrawing fiat in paper notes is one way to increase the finality of settlement. But that is not final either because the notes can always be revoked by the central bank and can easily be devalued by local fiat nodes, or the Fed’s full node.

The Underlying Technology

The core functionality of the fiat standard lies in the functions of the network’s nodes. Under the fiat protocol, each central bank has these four important functions:

- A monopoly on providing the domestic fiatcoin and determining its supply and price

- A monopoly on clearing international payments

- A monopoly authority for licensing and regulating domestic banks, holding their reserves, and clearing payments between them.

- Lending to the national government by buying government bonds

To perform these functions, each central bank has a cash balance, commonly referred to as the International Cash Reserve Account. This is the base-layer fiat token, which has the highest spatial salability, as it can be used to perform settlement between national central banks. In what is arguably the most catastrophic engineering decision in all of human history, this cash balance is used to perform four simultaneous functions, the intermingling of which is at the root of all financial and monetary crises of the past century. They comprise:

- Backing the local currency

- Settling international trade

- Backing all bank deposits

- Buying government bonds to finance government spending

Each of these tasks is discussed in more detail below, before the implications of their co-mingling are examined.

1) Backing the local currency

No form of money has ever emerged purely through government fiat. Statist economists like to speak of the state’s ability to decree what money is, but the existence of central bank reserves illustrates the limits of that view. No government is able to decree its own debt or its own paper as money without holding other assets it cannot print in reserve, and using them to make a market in its paper and debt obligations. Even if a government were to force its people to accept its paper at an artificial value, it would not be able to force foreigners to accept it, and so if its citizens want to trade with the world, the government must create a market in its currency in other currencies. Unless the government accepts foreign currencies in exchange for its own, then that market cannot emerge and its own currency is rendered worthless since nobody would want to hold it when they could hold other, harder currencies which have more salability across space.

Even through the century of fiat and supposed gold demonetization, central banks have massively increased their gold holdings, and they continue to add to them at an increasing pace. The fiat standard’s main reserve currencies are used to settle trade between central banks, but evidently central banks themselves don’t believe they have demonetized gold, and don’t trust in their ability to hold value into the future, and so they continue to include increasing quantities of gold in their reserves. All fiat currencies that exist today are issued by central banks that hold gold in reserve or by central banks that hold currencies in their reserves issued by central banks that hold gold. This not only illustrates the absurdity of the state theory of money, but it also illustrates the fundamentally unworkable nature of political money on an international level. If every government could issue its own money, how and at what value would they trade with one another?

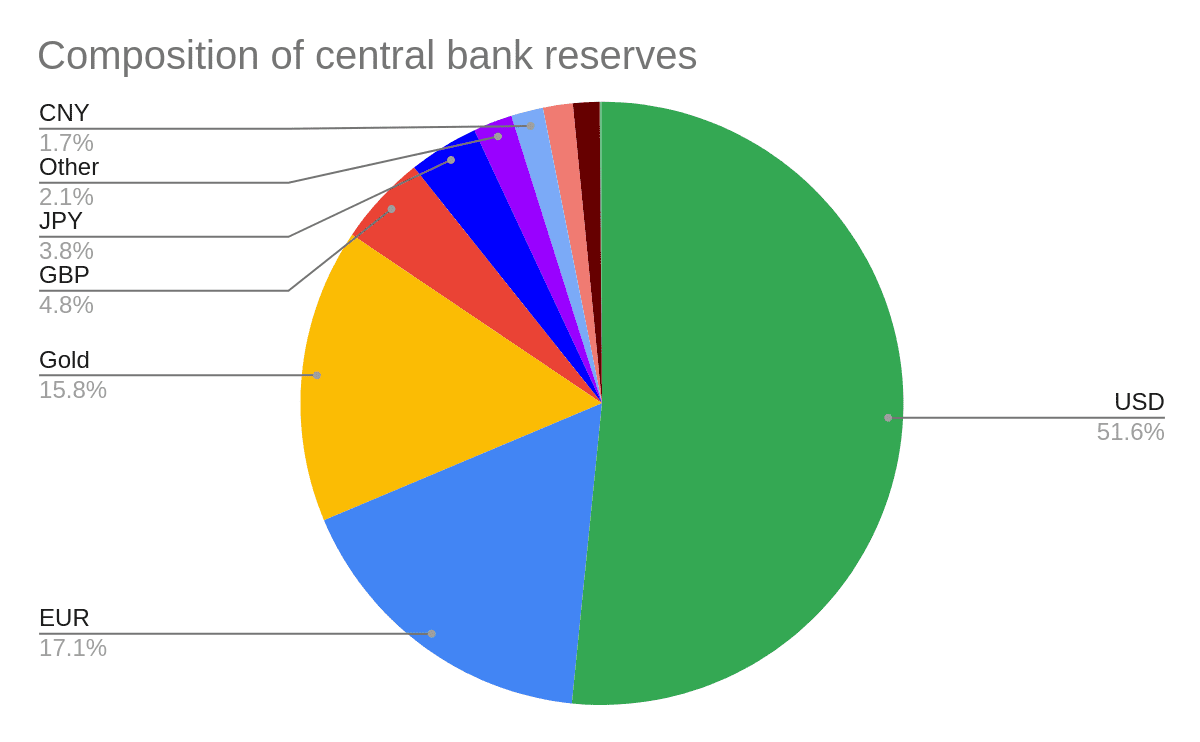

All central banks back their currencies with international reserve currencies they cannot print. For most countries, this is the US dollar, and for the US, it is gold. At the end of the third financial quarter of 2020, the dollar constituted around 51% of global reserves, the Euro 18.3%, gold 13.7%, the British pound 4.1%, the Japanese Yen 5.2%, and the Chinese Yuan 1.9%. Other currencies had smaller shares. The dollar has the lion’s share of the foreign exchange market, taking part in 88.3% of all the foreign exchange market’s daily trades.

The dollar is the base layer token of the world fiat network, and national currencies are derivatives of it. There are in total 180 national currencies in the world today. Other than the dollar and euro, national currencies are mainly used domestically in the secondary national fiat banking layers.

Figure 2: Central Bank and Foreign Reserves. Source: IMF And gold.org

Figure 2: Central Bank and Foreign Reserves. Source: IMF And gold.org2) The international cash account

Central bank reserves also settle the international current account (which includes international trade transactions) and the international capital account (which settles international movements of capital). All international payments to and from a country have to go through its central bank, allowing it a strong degree of control over all international trade and investment activities. Central bank reserves are enriched when foreign investment flows into the country or exports increase, but reserves are depleted when foreign investment leaves the country or imports increase. As individuals across national borders seek to transact with one another, they must necessarily resort to a system of partial barter, as Hans-Hermann Hoppe termed it, wherein they need to buy a foreign currency before buying the foreign good. This has led to the enormous growth of the foreign exchange industry, which only exists to profit from the arbitrage opportunities generated by the ever-shifting values of national currencies. This also effectively makes governments and their central banks third parties in every international transaction their citizens have with foreigners.

By also using national reserves for the settlement of international trade, a country’s international trade is held hostage to the central bank’s successful management of its currency. If the creation of debt were to increase quickly, the value of the national currency would decline against other currencies. The central bank would have to start depleting its international reserves if it needed to stabilize the value of its currency, compromising its ability to settle trade for its citizens.

3) Bank reserves

Central bank reserves ultimately back the banking system’s reserves. Central banks were intended to be the entities in which commercial banks would hold part of their reserves in order to settle with each other without having to move physical cash between their headquarters. Under a fractional reserve banking system, the central bank also uses its reserves to provide liquidity to individual banks facing liquidity problems. This means that the inevitable credit contractions that follow the banking system’s credit-fueled booms are remedied by central banks using their reserves to support illiquid financial institutions, in effect increasing the money supply. Given that central banks make markets in their domestic currencies relative to foreign currencies, if credit expansion were to increase the supply of a domestic currency and a central bank’s foreign reserves were to remain unchanged, the domestic currency would be expected to depreciate against foreign currencies.

4) Buying government bonds

The modern central bank and government song-and-dance routine adopted over the world involves the central bank using its reserves to purchase government bonds, thus financing the government. Central banks are the main market maker in government bonds, and the extent of a central bank’s purchase of government bonds is an important determinant of the value of that national currency. As a central bank buys larger quantities of its government’s bonds the value of the currency declines, since it funds this purchase by inflating the money supply. As time has gone by and monetary continence has continued to erode, central banks today do not just buy government bonds but are also engaged in the monetization of all kinds of assets, from stocks to bonds to defaulted debt to housing and much more.

The intermingling of these four functions in the hands of one monopoly entity protected from all market competition is ultimately the root cause of the majority of economic crises afflicting the world. It is easy to see how these four functions can conflict with one another, and how a monopolist will have the perverse incentives to look out for their own interest at the expense of the long-term value of the currency and thus the wealth of the citizens.

Maintaining the value of the currency would arguably best be served by using hard assets as reserves, in particular gold. But the second goal, settling payments abroad, is only doable with the US Dollar and a handful of government currencies used for international settlements. So central banks’ first conflict is between choosing a monetary standard for future needs vs one for present needs. This dilemma of course would not exist in a global homogeneous monetary system such as a true gold standard, since gold would offer salability across time and space.

Not only are governments likely to pressure their central banks to buy their bonds, but they are also likely to lean on their central banks to engage in expansionary monetary policy to “stimulate” their economies. This has a similar effect of inflating a country’s money supply and lowering the value of its currency against other currencies. By engaging in inflationary monetary policy, governments endanger their foreign reserves. Individuals start looking to sell the local currency for harder currencies, which creates more selling pressure on the local currency against other currencies. This forces the local central bank to sell some of its international reserves to attempt to stabilize the exchange rate. These individuals will also seek to send their newly purchased international currencies abroad to be invested in other countries. This could lead the government to impose capital controls to stop that flow in order to maintain its foreign reserves.

Similarly, as these individuals expect the value of their national currency to decline, they are also more likely to purchase durable goods rather than hold on to cash balances. This can mean increasing imports of expensive foreign goods, which also depletes the central bank’s foreign reserves. The government is then likely to retaliate with trade barriers, tariffs, and subsidies. Trade barriers are intended to discourage the local population from converting their local currency to international currency and sending it abroad. Tariffs are intended to reduce the flow of reserve currency abroad and to force importers to hand over reserve currency to the government as they import. And export subsidies are intended to encourage local exporters to increase their inflows of foreign reserves. This context helps us to understand how the collapse of the fiat system in 1929 ultimately gave rise to the protectionism of the 1930s, worsening the economic depression and fueling hostile nationalism.

The last two points are extremely important for the developing world because they have enormous implications for the three drivers of economic growth and transformation: capital accumulation, trade, and technological advancement. As governments restrict the ability of individuals to accumulate or move capital and goods, it becomes ever harder for individuals to accumulate capital, trade, specialize, and import advanced technologies. The global monetary system built around government-controlled central banks effectively puts local capital markets and all imports and exports under governmental control. They can dictate what can enter and exit their countries through their control of national banking sectors. The fact that governments can always squeeze imports, exports, and capital markets for foreign exchange revenue makes them very attractive borrowers for international lending institutions. Countries’ entire private economies can now be used as collateral for governments to borrow from the global capital markets.

At its essence, the fiat standard destroys savings and the ability to plan for the future in order to operate a payments network. As a thought experiment, imagine what would happen to a country that adopted a fiat standard before accumulating significant industrial capital. This is the position the developing world finds itself in today, as will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 11.